Diverse Perspectives on Disability, a course I took last quarter, examined how disability interacts with the world from numerous viewpoints. Over a period of ten weeks, we learned from professors, parents, students, and professionals. On the first day of class, we were asked to define disability. When elaborating on our definitions, a student in the class commented:

“A person in a wheelchair only has a disability if there isn’t a ramp.”

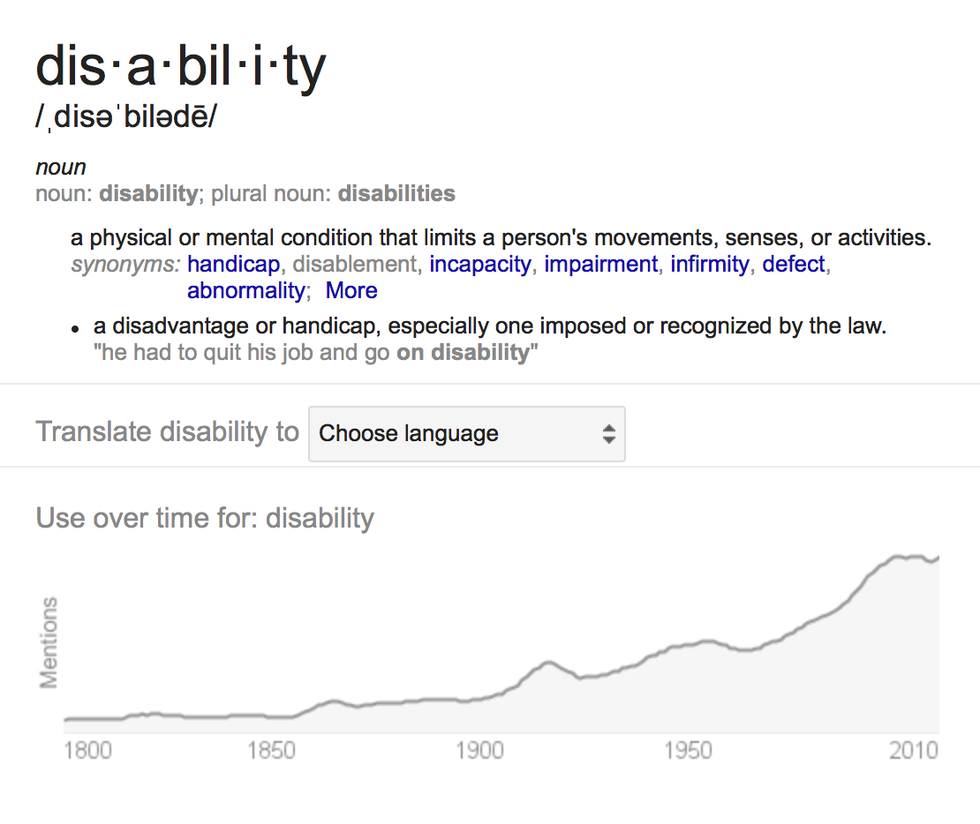

And, the more I think about it, the more I realize the extent to which her words are true. If people’s actions are not “limited” or “disadvantaged” (as according to the definition of disability above), do they really have “disabilities”?

I absorbed many life lessons from this class, including the one mentioned above. The following are some more messages I have learned and plan to keep with me for the rest of my life, and I want to share them because I hope you are able to value them, too.

1. Language is so, so important.

I had never heard of ableist language (defined as any word or phrase that targets an individual with a disability) before this class, but words like “crazy,” “moron,” and “dumb” were historically used as derogatory terms against people with disabilities. Similarly, we learned to always use person first language, which prevents any group from being defined by, and dehumanized because of, a condition. A “person with a disability” is a person first who happens to have a disability; this differs from the phrase “disabled person,” which emphasizes disability first and uses a condition to label a person’s humanity.

2. A person is always a person first.

Going off of Life Lesson #1, people are always people before they are anything else. This lesson rings true for much more than ability; race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, family decisions, sexual orientation, and lifestyle choice, to name a few. These aspects make up a portion of who we are, but we are all still dynamic and unique individuals and want to be considered as such. So many of the children I’ve worked with through Kids With Dreams have unparalleled appreciation and genuine joy for life. And some don’t; people are humans, and humans have great moments and not-so-great moments. (Similarly, the media rarely represent people with disabilities as people before their disabilities; often, characters with disabilities are defined their level of ability.)

3. Focus on ability, not disability.

People are so much more than their disabilities. Take Leonardo da Vinci, Jerry Seinfeld, Steven Spielberg, Temple Grandin, Albert Einstein, Mozart, and Lionel Messi, to name a few well-known people with autism. In what world would we say these people have a “lack of ability”? And, if we make the argument that they might lack ability in some aspects of life, doesn’t that extend to everyone? We all have strengths and weaknesses, and one “weakness” should not define an entire person.

4. People, regardless of ability, are inspiring.

During the Parents Panel our class hosted, one mom mentioned, “If they have the motivation and someone believing in them, they can do so much.” The mom explained she told her daughter she can be in control of her life, and her daughter (who was also present) excitedly told us she got her driver’s license and was starting a cafeteria volunteering job in order to work towards her dream of working in the food industry. Hearing her story motivated all of us. One student in the Students Panel with a speech impediment explained that she became a world-champion public speaker, and another basically reformed STEM education for students in India who lack vision. A common thread among these stories is that these people turned what society considers a weakness into strength. They worked hard to achieve their goals, and this industriousness allowed them to continue to succeed.

5. Disability is diversity.

We need a new word for “disability.” Disability, contrary to the dictionary definition, is not lack of ability, but rather different ability; think “abilidiversity.” We need to create physical spaces where people with disabilities can join together in solidarity, and we need to celebrate interacting with people who can give insight on different ways of life in general. Ability is simply another criterion to consider, because remember: people are people first. Diversity makes every group richer and stronger, from friend group to professional companies. I know that I still have so much to learn, even after taking this class, and adding to the collection of stories I carry with me can only help me grow.

6. Labelling people with disabilities limits everyone.

A disability is a portion of a whole person. The fact that it’s prioritized over kindness, courage, and other personality traits is because it’s an obvious label used to distinguish people. In some cases a disability is visible, and sometimes a disability is invisible, but regardless: labels limit people. Classifying everyone into groups is easy, because then we do not need to consider that every person is a unique, dynamic individual who wants to be accepted and wanted. When we label and stereotype, however, we limit ourselves in addition to the people we categorize, because we prevent ourselves from assessing a whole person. We take the easy way out.

7. Disability is relevant to everyone.

Whether or not you or someone you love has a disability, disability is relevant to you. We as humans need to look out for each other, especially for those of us who are privileged to not have a diagnosed “disability.” Furthermore, differing perspectives are crucial to helping us grow, listen, and empathize; many people have truly poignant narratives full of pain, resilience, and triumph, but they cannot share their experiences if we don’t ask. And, if this life lesson doesn’t resonate with you, remember:

8. Disability is the only minority group that any one of us can join at any point in our lives.

Think about it. It’s true.