Who knew biology deserved a copywriter’s touch? “Mother Nature’s gift,” “surfing the crimson wave,” and “a visit from Aunt Flo,” are only a few of the many euphemisms for “that time of the month,” and all have appeared in major forms of media or advertisements so frequently that these phrases have transferred over to everyday language. Because of the United States’ consumerist society, which emphasizes that goods give meaning to people and their role in society (Cross 1), it’s not a woman’s period when she’s speaking in public, it’s simply “it,” and the advertising executives as well as the medium that these types of ads appear in are largely responsible for turning a simple (slightly annoying) act of biology into an embarrassing event just for profit. Only in recent years has the discourse featured in advertisements for menstruation products been changing for the better by reviving confidence in young ladies around their periods instead of inciting worry, but due to the long held and still dominant patriarchal ideology, change for advertisers will be slow. Since the boom of the advertising industry in the mid to late 1800s, Americans have chiefly shaped their identity around the advertisements they see in various media texts and the products that they consume. Ads for menstruation products are no different. Media and advertising executives have played on women’s self-esteem to reinforce ladies into a slightly docile position due to society’s dominant beliefs; however, hegemonic negotiation is beginning to enter the media rhetoric with ads such “First Moon Party” by HelloFlo, pushing back against obviously patriarchal ads from companies such as Kotex.

The media and advertising industries skyrocketed with the introduction of the telegraph during the second wave of the Industrial Revolution. For the first time, areas could be instantaneously connected; newspapers could feature breaking news from around the country and the world. And, as technology became more advanced, manufacturers could promote their products to a wider audience by purchasing ad space in various media. Competition between manufacturers producing similar products then arose, which caused companies to hire advertising firms to differentiate and brand a product as well as purchase more ad space. As advertising took more of a predominance in helping to fund mass media, a common hegemonic message was born, and everyone accepted it.

Although people wish to think that themselves and their beliefs are entirely unique, in reality, a large majority of the population shares at least several common themes in their ideology due to the predominance of media industries in our everyday lives. Of all the ideological state apparatuses (ISAs), which promote dominant ideologies non-violently, the media is the most pervasive: “the media has more influence on cultural ideas and ideologies than do schools, religions, and families combined” (Benshoff and Griffin 13). Unknowingly, the general population has allowed the few media executives to push their own ideological agenda through hegemony because people know no other way; whatever the media pushes is deemed “common sense” (Campbell, et al. 480-81). Media executives are able to get their largely patriarchal messages across through mass media, which consists of newspapers, magazines, television, radio, and the Web with the Internet. Critics Benshoff and Griffin assert, “Since this wealthy group has almost exclusively been comprised of white men, the dissemination of racist and sexist stereotypes has helped keep people of color and women from moving ahead economically” (9). Advertising has allowed executives to consistently promote a patriarchal message, stereotyping women along the way, which causes consumers to lock that image into their heads. In a large part, the media is the reason young girls look at themselves questionably after flipping through several magazines. The media is one of the reasons girls and women are deemed inferior. The media helps to warp our values.

Part of the reason that Americans are so willing to absorb the patriarchal messages pushed by advertisements is because the United States has transformed into a consumerist society in the twentieth century. Historian Gary Cross argues, "Many factors contributed to this. The absence of a national church, a weak central bureaucracy, the regional division of the elite, the lack of a distinct national ‘high culture,’ the fragmentation of folk cultures due to slavery and diverse immigration, and finally the social and psychological impact of unprecedented mobility” (4). People express themselves through the goods they consume. Additionally, the hastened rise in modern technology has caused us to no longer need to restrain our desire for products, creating a culture of “I want.”

The key to continuing to a consumer culture is advertising. Ads create meanings for products, and people are only receptive to advertisements if the content in them is relatable: “Advertising is the product of creative intuition, and inflicted by particular and historical styles and tastes” (Leiss, et al. 170). Thus, ads produced since the proliferation of the media have reflected the patriarchal beliefs of a select few, which in turn, has caused women overall to think lesser of themselves in the past and still partially today because the media is such as strong ISA. The result of this dominant patriarchal message has caused ads targeted towards women to revolve, for example, around their appearance to only please men. This targeted advertising has caused people's values to realign with what society portrays to be the dominant ideology, which, in reality, was first the beliefs of a few media executives able to push their message effectively. Menstruation products have not escaped this patriarchal message.

Throughout the last 100 years, the rhetoric featured in advertisements for menstruation products has largely stayed consistent despite ads changing artistic styles and forms over time. When not trying to promote the fact that tampons are safe to use, advertisements from the 1940s and into the 1950s attempted to differentiate similar brands by invoking several persuasive strategies such as fear to prove that their product would make girls behave normally again or cause boys to not turn away. The effect of the rhetoric in these forms of advertising caused women to feel embarrassed about their period. In turn, these types of advertising strategies continued to enforce the dominant patriarchal belief that women are not equal to men.

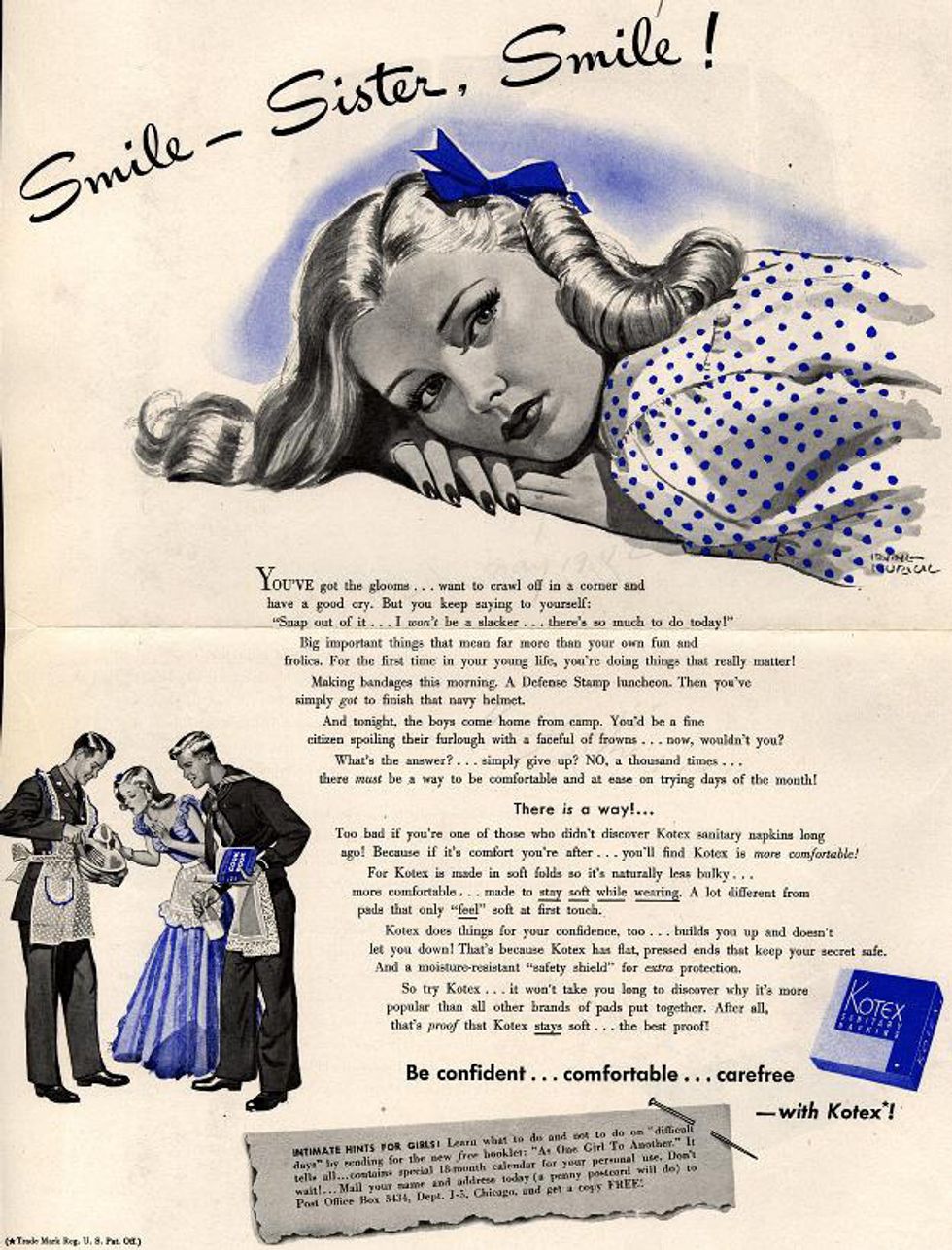

In the 1940s, the brand Kotex was particularly adept at reinforcing the dominant beliefs regarding ladies at the time. In a 1942 advertisement for sanitary napkins, or pads, that appeared in the magazine, Ladies’ Home Journal, ad men used several persuasive strategies to play on women’s emotions and continued to assert the dominant ideology through different phrases and images.

The main goal of this Kotex ad from 1942 that appears in Ladies’ Home Journal is to have the audience “be confident...comfortable...carefree--with Kotex!”; however, this ad does anything but promote its brand slogan. Throughout, the ad puts women down until the very end when it states that women can make themselves feel confident again by using a Kotex pad. Yet, women accepted this message because of the dominant patriarchal ideology already ingrained in their minds. Furthermore, it is evident that women believed this message because it appeared in a popular women’s magazine. The women of the 1942 were not stunned when they saw an image of a depressed girl meant to be on her period or read the horrendously patriarchal text.

Due to the fact that the Kotex ad emphasizes the direct relationship between a product and person and includes the menstrual product in a social setting, this ad is a combination of the personalized and lifestyle format, respectively. Leiss, et al. explains, “In personalized ads, people are explicitly and directly interpreted in in their relationship to the world of the product. Social admiration, pride of ownership, anxiety about lack of use, or satisfaction in consumption become important humanizing dimensions of the interpretation of products” (184). Though not as predominant as the personalized format, which creates a fear around a period only remedied by Kotex, this ad is still representative of a lifestyle format because it integrates the pad into a consumption style by portraying a jolly girl surrounded by men. Furthermore, this Kotex ad is largely text based in order to differentiate from brands like Always: “In the earlier period especially, the text explains the reasons for consuming, the identity of the user, the appropriate context for use, or the benefits of the product” (169). However, the text does not really emphasize why the product is better than others, only how it will make a woman feel better; it’s not entirely rational: “If advertisers also believe (and they do) that women are less rational consumers than men, this will be revealed in the fact that the more rational forms of advertising occur less often for women’s products and in women’s magazines” (202). It never gets into the real specifics of absorbency or even show an image of the actual pad because it is easier to use tactics such as the hidden-fear appeal or the bandwagon effect, which claims everyone is using a product, to convince ladies to buy the product and keep pushing the patriarchal ideology.

More specifically, the ad represents the presiding patriarchal belief and continues to convince women of it through its images and text, which make it seem as if it is a woman's fault for getting her period and inconveniencing others. The main image of a depressed but pretty girl painted blue automatically presents the idea that a woman should feel somewhat ashamed and are more so too emotional. Additionally, the Kotex ad presents women as lazy during their time of the month: “I won’t be a slacker.” Furthermore, the text implies that a woman's period can be an inconvenience to men and the country: “For the first time in your young life, you’re doing things that really matter! Making bandages this morning . . . And tonight the boys come home from camp. You’d be a fine citizen spoiling their furlough with a faceful of frowns...now, wouldn’t you?” When the ad finally mentions the product, it does so as discreetly as possible by calling a “period” a “secret” since it is alien to men that are advertising executives.

Only in very recent years has the discourse around women and menstruation changed with campaigns like Always’ #LikeAGirl but especially HelloFlo, an online service that sends you products for your monthly period. Ideologies are beginning to shift. Hegemonic negotiation, which is “the processes whereby the various social groups exert pressure on the dominant hegemony,” is happening due to the new wave of feminism in United States culture.

In 2014, HelloFlo released their second advertisement on YouTube, which tackled the stigma around periods once again. Entitled “First Moon Party” this ad tells the story of a standoff between a girl who can't wait to get her period, and a mom who can't wait to mess with her angsty tween daughter in order to prepare for the release of the company’s menstruation starter kit. HelloFlo’s ads evoke positivity around periods instead of the ad men from the past, which as “The Period Fairy” put it: “They had no idea what girl’s needed.”.

“First Moon Party” helps put periods back into the hands of women. Unlike the ads of the 1940s and beyond, “First Moon Party” ends the stigma around periods being featured in ads and different forms of media. Rather than featuring a girl embarrassed to have gotten her period, which is the norm, this ad introduces its audience to Katie who cannot wait to be a part of the “cherry slush club.” Additionally, the mother turns the “arrival” of her daughter’s period into a celebration. For HelloFlo, getting one’s period is not an embarrassing event; it’s a celebration of a new stage in life for all, including men, to be congratulatory. It’s significant that the first guest for Katie’s party is her grandfather, someone who would largely want to stay away from the subject due to age and gender; however, he’s excited. A period is simply part of biology, so why shy away from the topic? Furthermore, “First Moon Party” makes a light jab at the men who have long run the advertising business by one of the male guests bring coffee filters, thinking their pads, as a gift since he wasn’t sure which brand she liked. “First Moon Party” is a hilariously clever ad that is starting the hegemonic negotiation with the current patriarchal values.

Released on YouTube because the founder of HelloFlo did not have enough funds for advertising on other mediums, this ad is directed mainly towards mothers because it is them that first communicate with their daughter about puberty. Additionally, the second audience is young girls themselves because they have power to influence their parents’ purchasing decisions.

It’s not entirely surprising how menstruation products are being advertised is changing since the culture in the United States is in a constant flux. Hegemony allows this. In order to succeed with advertising to a large majority of women, advertising executives need to take advantage of this new wave of feminism in the United States, and in doing so, this will eventually create a new dominant ideology. HelloFlo is only the beginning.

Because of the predominance of the media in everyday life since the second wave of the Industrial Revolution, advertisers have been able to push the messages of top media executives and themselves so much so that today we accept these messages as “common sense.” One of the messages being pushed for a long period of time is the patriarchal idea that women are lesser than men. One Kotex ad for pads from the 1940s asks, “And tonight, the boys come home from camp. You’d be a fine citizen spoiling their furlough with a faceful of frowns...now, wouldn’t you?” By playing on a woman's emotions, ads such as this one from Kotex helped to keep women believing that they were at times lesser than men, but that is beginning to change. Dominant ideologies can shift because hegemonic negotiation is possible, and society is witnessing that with ads from companies such as HelloFlo. This company aims to end the stigma around periods and does so wonderfully with its second ad entitled “First Moon Party.” Women are now beginning to shape their identity around the messages of confidence and power pushed in these advertisements. Eventually, more advertisers and media texts will change their tune in order to sell products, and perhaps a period will no longer be thought of as the “red scare.”

Works Cited

Benshoff, Harry and Sean Griffin. “Introduction to the Study of Film Form and Representation.” from America on Film: Representing Race, Class, Gender, and Sexuality at the Movies (Second Edition). Malden: Blackwell Publishing, 2009. 3-17.

Campbell, Richard, et. al. Media Essentials: A Brief Introduction (3rd Edition). Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2016.

Cross, Gary. “The Irony of the Century.” from An All-Consuming Century: Why Commercialism Won in Modern America. New York: Columbia University Press, 2000. 1- 17.

HelloFlo. “First Moon Party.” YouTube. 17 Jun 2014.

--. “The Period Fairy.” YouTube. 12 May 2015.

Kotex Company. “Smile-Sister, Smile!” Ladies Home Journal, 1942. Duke Ad Access.

Leiss, William, et. al. Selection from “Two Approaches to the Study of Advertisements.” from Social Communication in Advertising: Consumption in the Mediated Marketplace. London: Routledge, 1997. 197-228.