RICHMOND, Va. (VCU Odyssey) – Living life with a substance abuse addiction behind bars is a time of personal reflection for inmates. But, thanks to Richmond City Justice Center’s “Recovering from Everyday Addictive Lifestyles” (REAL) program – in collaboration with Sheriff C. T. Woody, Dr. Sarah Scarbrough, and the McShin Foundation – the journey to release may also be a time of personal development.

Richmond City Justice Center, located in in downtown Richmond near Mosby Court, is innovating the transition back into the community for inmates.

REAL began in May of 2014 under the direction of Dr. Sarah Scarbrough, internal program director at RCJC, after obtaining her Ph.D. in public policy from Virginia Commonwealth University.

REAL offers RCJC residents the chance to participate in various lifestyle courses to address trauma and addiction specifically to ensure a successful reentry into the community.

“When 95 percent of the incarcerated population are going to be released, how do you want them coming back into your community?” Scarbrough said. “Better citizens or better criminals? Every day we are interacting with the justice community.”

“Recidivism is a lifestyle,” said Lynwood Rice, a resident at the Richmond City Justice Center who has been incarcerated nearly 10 times throughout the last 21 years. “When I get out, I go back to doing what I’m comfortable doing.”

Rice is currently fulfilling a one-year and three-day sentence, he said. Throughout the last 21 years, the jails he served in had very little rehabilitation to fix his criminal behavior cycle.

“I never had anybody offer me help,” Anthony Walters, a resident at RCJC who has been incarcerated as both a juvenile and adult, said. “I’m so used to being the provider … I’m trying to learn how to accept [when someone compliments me]. I used to be a violent person, but now I’m channelling that into other things.”

Rice and Walters are one of 1,032 men and women housed at RCJC. Virginia has the eighth highest jail incarceration rate in the U.S., with one in every 214 adults behind bars according to a 2013 report by the Justice Policy Institute (JPI).

JPI said the commonwealth has increased its attention on drug offenses as violent and property crimes have decreased.

“Jails and prisons, particularly crowded ones, provide very little treatment or reentry preparation for people who may have substance abuse disorders,” the 2013 JPI study said. “These people, if arrest is appropriate at all, should be diverted to treatment-based interventions.”

According to Scarbrough many of the programs are not “holistic in nature.” She said merely taking away the substance without rehabilitating the addiction proliferates the recidivism cycle.

“That 1960s mentality of ‘locking up and throwing away the key’ isn’t effective,” she said. “If you take away the drugs, you still have the behaviors.”

Recidivism is a continuing national epidemic with a high incarceration and substance abuse elimination price tag in the United States.

The National Institute of Justice defines recidivism as “a person’s relapse into criminal behavior, often after the person receives sanctions or undergoes intervention for a previous crime.”

The United States is the world leader in incarceration, with nearly 2.3 million adults behind bars in 2013, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS). Between 95 and 97 percent of inmates will be released at some point – however, approximately 75 percent will return to either jail or prison within three years of release.

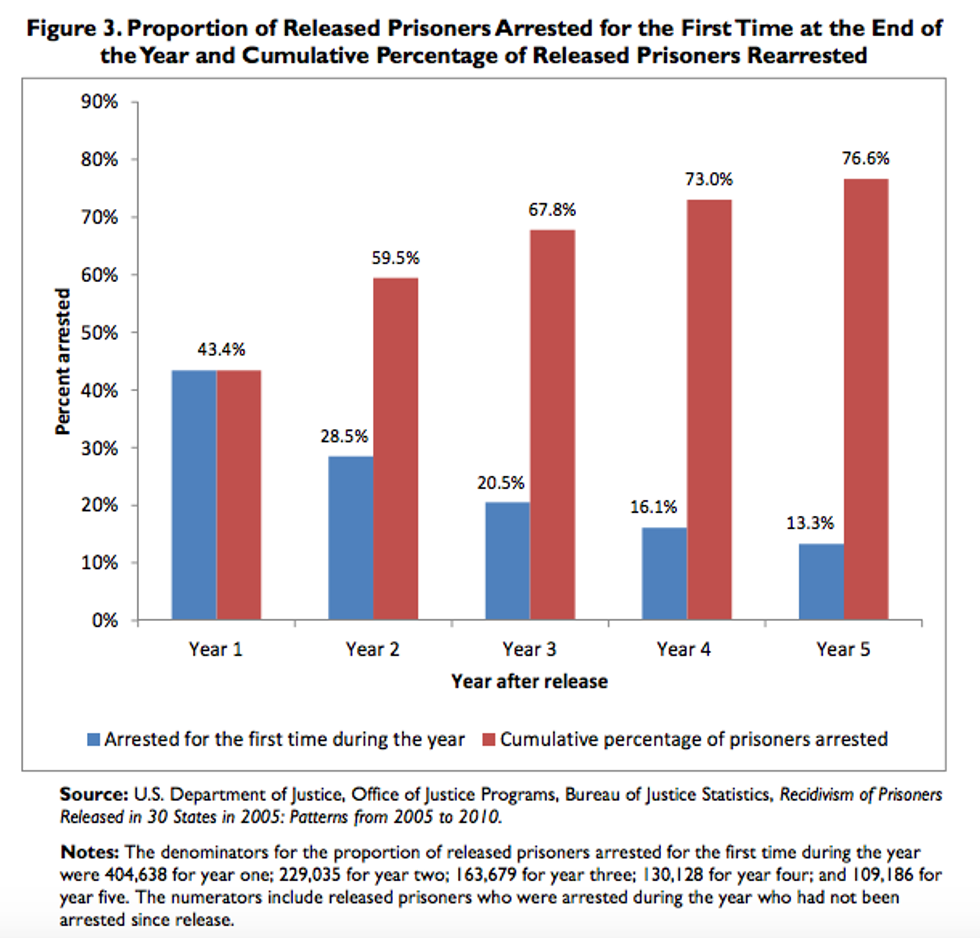

“What most people see is that we have a broken system,” said Snapper Tams, a law student at the University of Richmond and criminal justice advocate. “But the key is, we have a broken system that people now exploit.”Above: Rearrest percentages from the BJS recidivism study from 2005 to 2010. Retrieved from a 2015 report from the Congressional Research Service.

John Shinholser, president and board member emeritus of the McShin Foundation, struggled with substance abuse until 1982.

“There’s an old saying in recovery,” Shinholser said. “You get what you get when you do what you do.”

The McShin Foundation is the sponsor of five recovery and reentry programs in the Richmond metro area, including Scarbrough’s REAL program.

McShin’s mission is to eliminate the “irresponsible and punitive” practices many jails and prisons across the nation adopt to address substance abuse addictions and convictions, Shinholser said.

“You have to humanize the recovery process from addiction,” he said. “Our criminal justice system has demonized.”

So far, McShin has calculated an 18 percent reduction in recidivism and a cost savings of $8 million since the program’s inception in 2008.

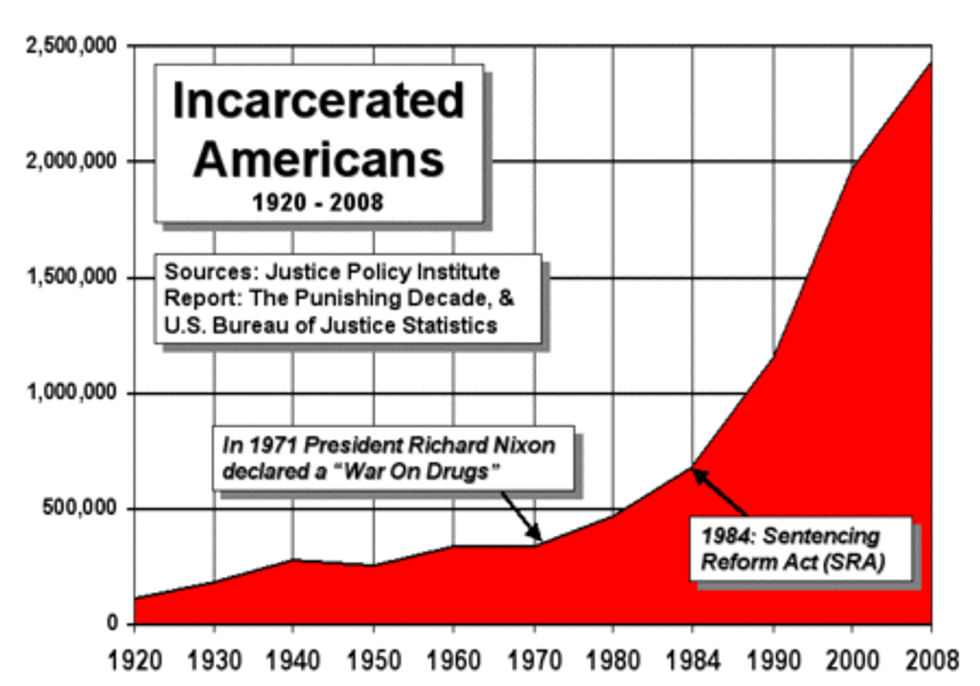

Since 1971, when then president Richard Nixon declared a “war on drugs,” the United States has increased its federal incarceration budget. The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) annual report states that fiscal year 2015’s budget was $8.5 billion.

According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the U.S. drug addiction rate has steadily remained at 1.3 percent from 1970 until today.

Above: Graph depicting U.S. incarceration from 1920-2008.

Nearly every state has some type of inmate reentry program. Most programs are targeted to specific areas of rehabilitation.

Programs such as the faith-based Boaz & Ruth, located in Richmond’s Highland Park neighborhood, have been assisting the incarcerated community for years by providing job opportunities and training to offenders transitioning back into the community.

President and CEO Megan Rollins said since the program’s inception about a decade ago, their recidivism rate has steadily stayed below 14 percent.

“We can help break the cycle through the individual rather than policy change,” Rollins said.

Boaz & Ruth serves about 1,200 people annually and offers ex-offenders the opportunity to work at their clothing and furniture thrift store, a public computer lab, a moving company picking up donations, and catering private events.

Bea Robinson, volunteer and community service coordinator at Boaz & Ruth as well as a graduate of their program has been with the organization since 2005. She came to the organization after serving in a federal prison for obstruction of justice.

Robinson said the only program offered at the federal prison she served at was a drug program. The incentive of that particular program was a sentence reduction, typically up to one year.

“It’s all about your character and how you present yourself,” she said. “[Boaz & Ruth] as far as recidivism, it’s a good deterrent. The lack of education, money, food, housing, clothing [causes recidivism].

“You’ve got people who have been incarcerated or are incarcerated not going through mandatory programs, so they just float around all day long.”

Many programs to help recidivism often have trouble obtaining funding. Programs such as Scarbrough’s REAL are fortunate enough to receive donated classes, which has prompted the start of turning REAL into a non-profit.

According to Rollins, Boaz & Ruth partners with the AmeriCorps organization to obtain funds, but said the resources are not always feasible.

“We have the capacity to serve more,” Rollins said. “But we’re really looking toward more social enterprises that will allow us to pay [people] again. We think it’s critical [to help inmates back into the community].”