Earlier last month, Kanye West initiated an outraged rant about Kid Cudi during the Saint Pablo Tour in Tampa, Florida. I know because 1) I was two rows from the concert floor when the drama unfolded and 2) within minutes, it went viral. Admittedly, it had been a while since Cudi’s name had even come to my mind, and so despite my loyalty to Mr. West, I ended up on Cudi’s Spotify page moments after leaving the show.

Soon enough, I found myself cycling through tracks from my teenage playlists: “Day N’ Night,” “Erase Me,” “Pursuit of Happiness.” Like many young adults, I had been consumed with feelings of doubt during that point in my life, which Cudi uniquely tapped into. A few years later, I’m in a better place and realize that life will always be a transition; you’re constantly upgrading to your latest personal iOS. Regardless, these songs still speak to a part of me--the appreciative 16-year old me that desperately needed to hear someone else say that life was hard.

Cudi’s hip-hop beats mesh carefree verses with messages of isolation, doubt, and growth, which blatantly present themselves in his “Soundtrack to My Life,” wherein Cudi’s chorus confesses the following:

I’ve got some issues that nobody can see/

And all of these emotions are pouring out of me/

I bring them to the light for you/

It’s only right.

Fast forward seven years from that song’s release on Man of the Moon: The End of Day and it’s no surprise that Cudi has now formally declared himself as a victim and survivor of depression, while his fans praise him as an advocate and an artist. Recurring themes across Cudi’s albums are the use of drugs, sex, and alcohol to numb emotional pain. Not surprisingly, these themes are popular across most music genres, be it in country or rock. However, the pace of Cudi’s songs seems to almost underplay the depression he constantly shares with listeners. If you weren’t listening closely, you might be able to party the night away to his bass-bumping struggles.

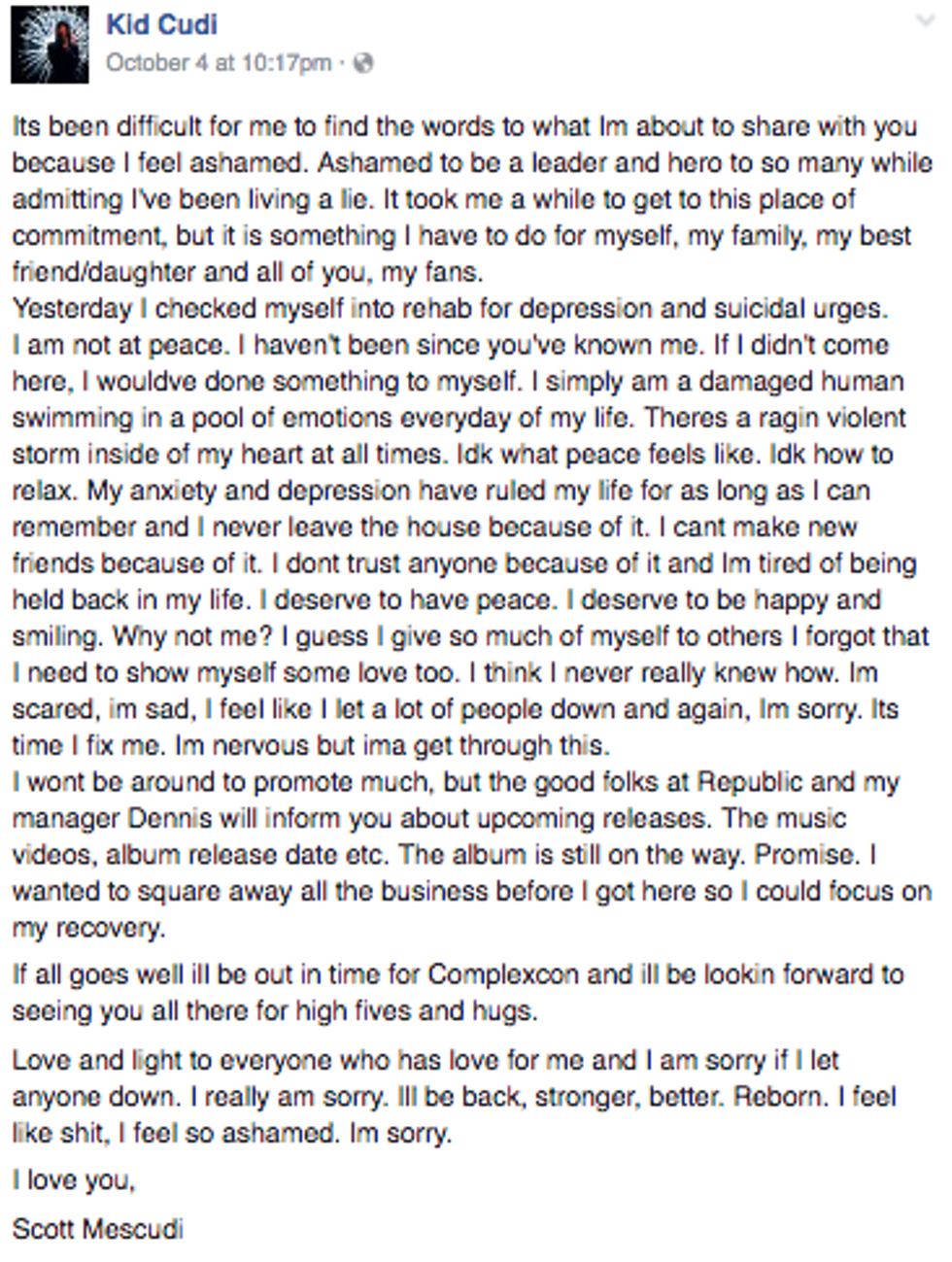

Late night on October 4, Cudi admitted on his Facebook page that he had checked into rehab for both his depression and anxiety, conditions he claims have been affecting him his entire life. In addition to this update, Cudi delivered an apology to his fans, signing off with his legal name, Scott Mescudi. Cudi’s raw emotion left a deep impression with his followers; the post has been liked more than 576,000 times, shared more than 136,000 times and received over 56,000 comments on Facebook alone.

It’s well understood that depression is dismissed in our culture, affecting 15 million Americans and another 40 million when we include anxiety disorders. Americans are told that depression is something you can smile away, but also something that defines you enough to reduce your value. Triggers can come suddenly, or gradually, and are only accelerated with anxiety. The loved ones you know that have depression never forget they have it for long. Depression is the confusion of loneliness in a bustling room paired with the shame of dark thoughts that swim in an empty room. Having depression means acknowledging that there is no ultimate victory; there is no endpoint in a lifelong battle with yourself. You may win on one day, but it will win on others.

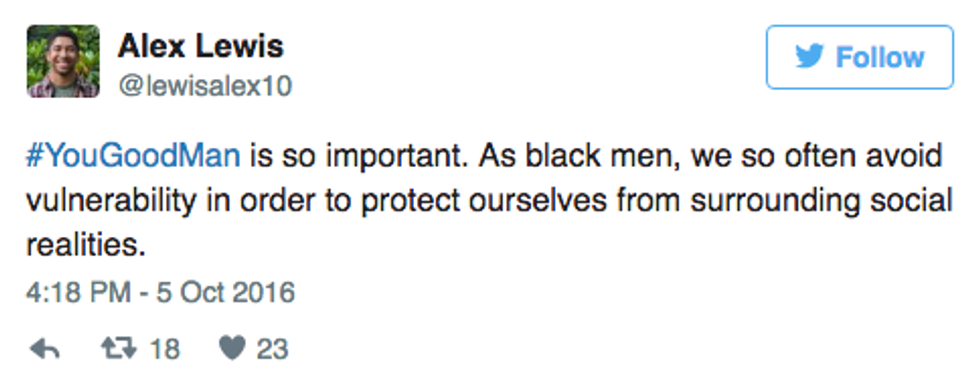

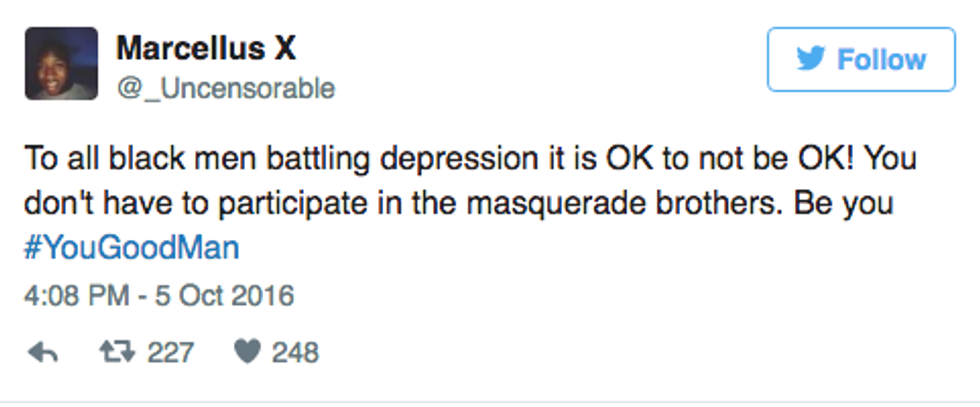

However, we are also told one’s value remains influenced by their skin color, and in a society where the Black community has to riot in the streets to be heard, there are unique factors that contribute to Black mental health that America isn’t properly acknowledging. There’s a stigma to being depressed that multiples for our men. We don’t give one another consent to be vulnerable, and for men we call that behavior “weakness.” We’ve been raising our sons, encouraging our brothers, and urging our friends to “man up” and swallow their own inner turmoil. We have given them the options to either admit defeat or suffer in silence. In both nonverbal and verbal ways, we never stop telling men to avoid vulnerability, and then one day it becomes their default.

Although Cudi isn’t the first celebrity to openly discuss depression nor will he be the last, he does represent a key underrepresented demographic: the black male in America. His exit from social media early last week sparked a necessary conversation with tweets pouring in to talk about mental health, particularly for Black men, with the trending question #YouGoodMan.

Mental health is gradually easing its stigma in the US, but as with many privileges, this trend has started from the top-down. Mental health services are disproportionately available within White communities, those with the luxury and finances to set aside regular time in counselors’ offices. A cruel reality in the US is that our Black communities are overrepresented in our prisons and underrepresented in our mental health spheres. Our Black teenagers are more likely to attempt suicide than our White teenagers, and our Black adults are 20 percent more likely to report serious psychological distress than those in White communities. It’s our system that’s broken, not our people.

The ultimate source of healing ironically has to come from within during mental health treatment, as Cudi himself suggests. He had to square away his business to be in the right state of mind for a personal transformation. Today, we are all rooting for him now and upon his return. In the meanwhile though, we have to turn these conversations outward and keep them alive. As a White woman, I'll never know the experiences of the Black community, but I do know that we can all do our part to heal together. Although the path to peace may be a long one, it can take us places we’ve never been.