Ramadan is the annual 29-30 day duration of fasting that all adult and most young Muslims go through to commemorate the first revelations of the Koran to the prophet Muhammad. During this fast, Muslims adhering to the practice will abstain from any lustful thoughts and will not smoke or consume anything from the break of dawn to the last light. And by that, I mean literally anything. No water, no Gatorade, no candy, nothing at all. For 30 days, no matter how thirsty you may get, you suck it up and wait until the sky turns dark.

In countries such as Brunei where Sharia Law is imposed, eating/drinking/smoking in public during Ramadan—regardless of your religion—is prohibited and punishable by jail time. Restaurants do not allow dine-ins, and even though pregnant women and children are exempt from these regulations, discretion still must be strictly observed.

I asked a few of my Muslim fellows in the army how they manage to keep up with both the demands of the military and their religion, and I was surprised at how nonchalant they were about the whole matter. To them, fasting was an obligation, a practice that they held ever since they were children. It was a part of their lives, and it was natural that they fasted during Ramadan. I was stunned. The most I have ever fasted was a meager 12 hour stretch, and even then I wouldn’t stop complaining.

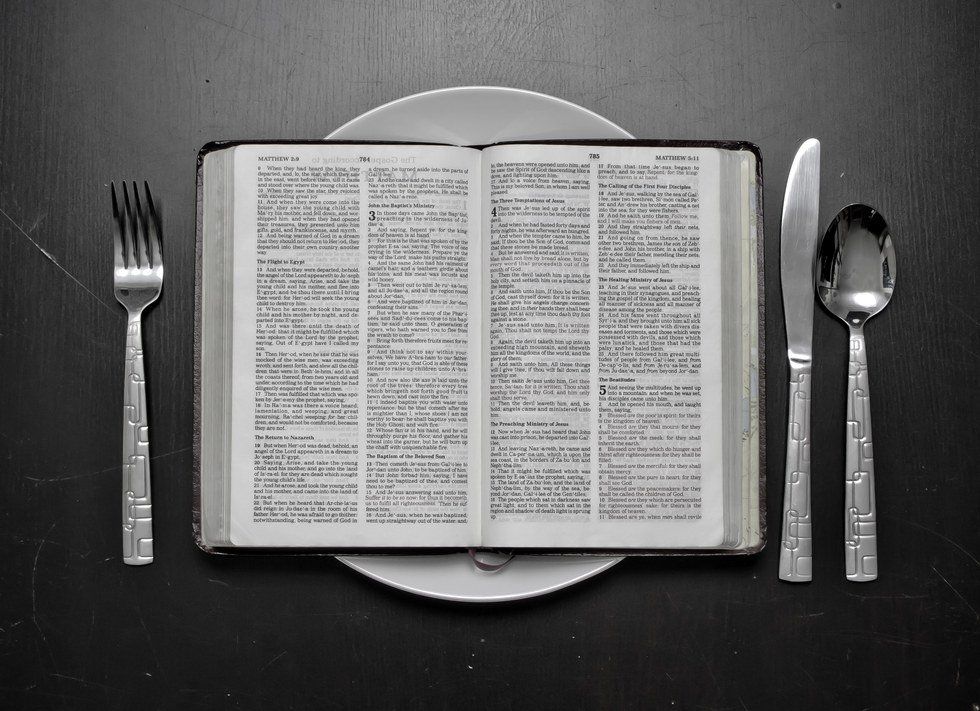

If we compare what most Christians do for Lent with Muslims in Ramadan, the vast disparity makes it rather depressing for the Christians. A youth group leader from Southland once told me that his group of guys actually deigned to suggest that they gave up porn for Lent. Most of the time, people would just settle for giving up a type of food for Lent. We would tell ourselves that it is the idea that counts, that as long as we understand why we give up what we give up and reflect daily on the sacrifice that Christ made for us, we’d be pretty set. After all, Christianity is very much stemmed in intentions.

As a religion of intentions, being a Christian can be very liberating. But in establishing a personal relationship with you Lord and Savior, intention is something ironically easy to overlook. “I mean, I’m sure that as long as I mean well, it’s ok, right?”

Now, I’m not saying that Christianity should become the state religion and fasting should be something that is imposed by force. I know that fasting is something that we should do on our own accord to come closer to God: in depriving ourselves of something essential, we learn to depend on the one from which all good things stem. But Christians these days aren’t exactly keen on fasting. The 30-hour famine is usually a pretty fun occasion. I mean, come one now. Can you really still call it a famine with a straight face? Is the freedom that we find in our salvation an excuse that we now use to avoid exercising discipline?

Jesus died for us so that we can find true freedom in the cleansing power of his blood. We fast, not as penance for our sins. We fast so that in our weakness, we can experience the fullness of God’s Grace. I realize that sounds oddly masochistic, but it’s true: the less we have, the less that we are, the more we come to see the richness of his Grace in our lives. Because when we are strong, we have a tendency to think that we are somehow in control of things.

There is so much for us to learn from the Muslims just in their dutiful adherence to Ramadan alone. As Christians, we have the freedom to serve God and His people out of Love, but this freedom is slowly corroding our practice of faith in the form of complacency. This cannot go on. We are a chosen people, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a people belonging to God, that we may declare praises of him who called us out of darkness into his wonderful light. Let’s start acting like it.