You might have heard Vaughan Williams's music without knowing it. Ever heard "For All the Saints"? He wrote its tune, so, if you've heard this (extremely popular) hymn at, say, a funeral, you've been exposed to him. He also wrote a beautiful arrangement of "All People That On Earth Do Dwell" for Elizabeth II's coronation, which I happen to know because it's a staple at my university's Baccalaureate Mass. In addition, he wrote a beautiful "O Taste And See" (which I know because we were going to do it this past semester in my university's church choir, though we didn't get around to it) and a personal favorite of mine, "O How Amiable", which we did sing this past semester in my choir and which I think of as one of the most beautiful pieces of music I know. Vaughan Williams, thus, well deserves his fame as a composer of church music. He has left an indelible mark on the use of many beloved and great melodies.

On the other hand, he occupies an important place in the history of British music for producing a distinctively "English" sound, strongly influenced by folksong (from his collecting we get this marvelously fun carol, which I know from singing in my university's Christmas concert) and English Renaissance-era music. Thus, as we can expect, we get a fun "Fantasia on Greensleeves", an English Folk Song Suite, a great set of variations on a popular tune called "Dives and Lazarus", a choral setting of the great Scottish folk song "Loch Lomond", the perennial favorite "Linden Lea", and a fantasia derived from Thomas Tallis. The Englishness of his music is further underscored by how he has a great choral setting ("Valiant For Truth") of a text from John Bunyan's "The Pilgrim's Progress." (Vaughan Williams also set "To Be A Pilgrim" from the same work. His version has the words a bit changed from the original, and I think that this version actually serves Bunyan's spirit a bit better.)

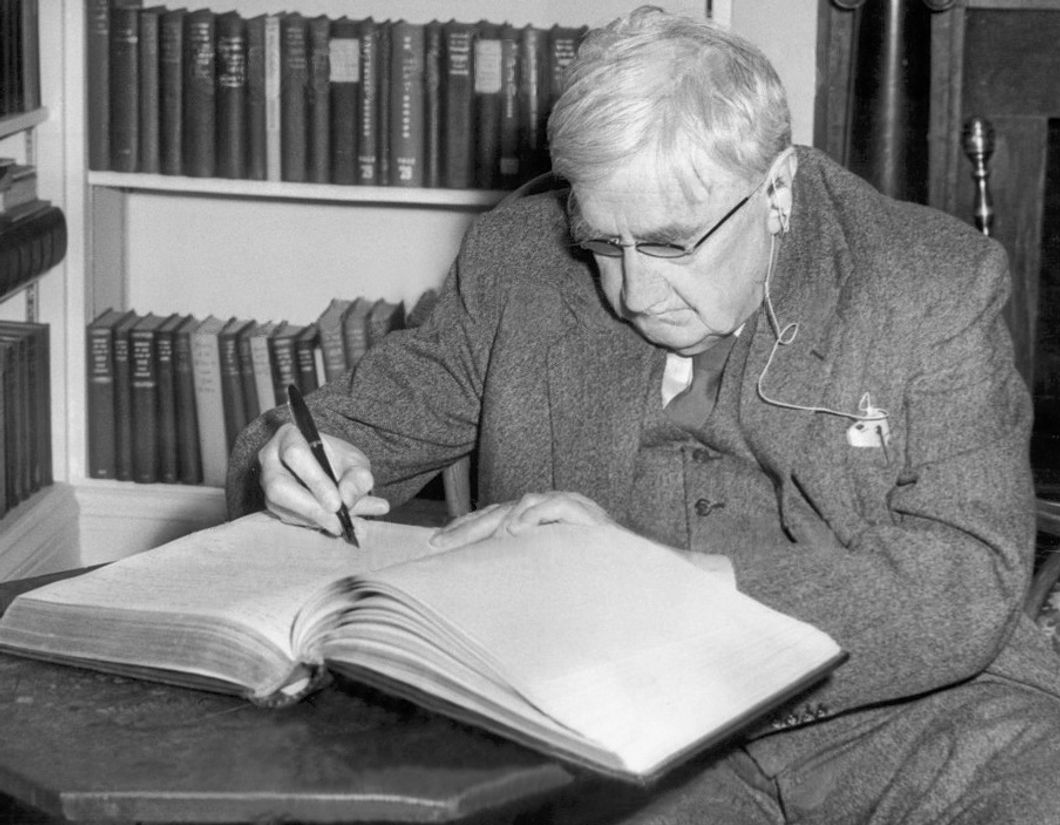

So, here we have Vaughan Williams, the industrious arranger of hymn tunes and folk music. That's all fine and dandy for church ladies and folk tune fanatics, and enough to cement him as an important composer worthy of great affection for augmenting the beauty in our lives. I was not aware, however, until I listened to a bit of his more grandiose compositions, that he was anything but a musical fuddy-duddy. In fact, the greatness of his work, its scale and its scope, really sets him up as deserving to be placed among the greats.

Just listen to his "Dona Nobis Pacem". (I actually really do recommend that you do.) It absolutely blew me away. It is a totally sophisticated interweaving of simple liturgical text, great poetry (Walt Whitman for the win!), chorus, and soprano solo all completely infused by a fervent plea for peace. (He notably wrote it in the period leading up to World War II.) His Benedicite, his "Sancta Civitas" (an oratorio version of the Book of Revelation), his very cool "A Vision of Aeroplanes", and his beautiful polyphonic Mass in G Minor are all worthy of recognition. "Five Mystical Songs" (a setting of poetry by George Herbert) and "The House of Life" (a setting of Dante Gabriel Rossetti) are beautiful, and they are good evidence above all that the composer who found his niche in his country's folk music and religious tradition perfectly wedded that interest with serious music-making.

Vaughan Williams, as great as Britten who followed him, enjoys a wonderful distinction, having achieved something marvelous. He both enriched the progress of modern music (and enriches us when we listen to and perform him) and leaves us humming. What more could a composer wish for?

Lumiere figure at the Disney Store at the Ala Moana Shoppi… | Flickr

Lumiere figure at the Disney Store at the Ala Moana Shoppi… | Flickr

StableDiffusion

StableDiffusion StableDiffusion

StableDiffusion 10. Extra BlanketsJuwenin Home 100% Cotton Knitted Throw Blanket

10. Extra BlanketsJuwenin Home 100% Cotton Knitted Throw Blanket StableDiffusion

StableDiffusion StableDiffusion

StableDiffusion File:Kishlaru familie.jpg - Wikimedia Commons

File:Kishlaru familie.jpg - Wikimedia Commons Photo by Hanna Balan on Unsplash

Photo by Hanna Balan on Unsplash StableDiffusion

StableDiffusion black blue and yellow round illustrationPhoto by

black blue and yellow round illustrationPhoto by

woman holding glass jar

Photo by

woman holding glass jar

Photo by