There are many notable numbers: 1066, 420, 3.14, and so on, each with a unique meaning. But one number deserves greater attention: 1,041. That’s the percentage rise of the costs of college textbooks have increased in the past three decades: 1,041%.

It is a dangerous number. It makes affordable education difficult. It is political. And as “3” is to trinity and “1.618” is to the golden ratio, “1,041” represents economic malpractice.

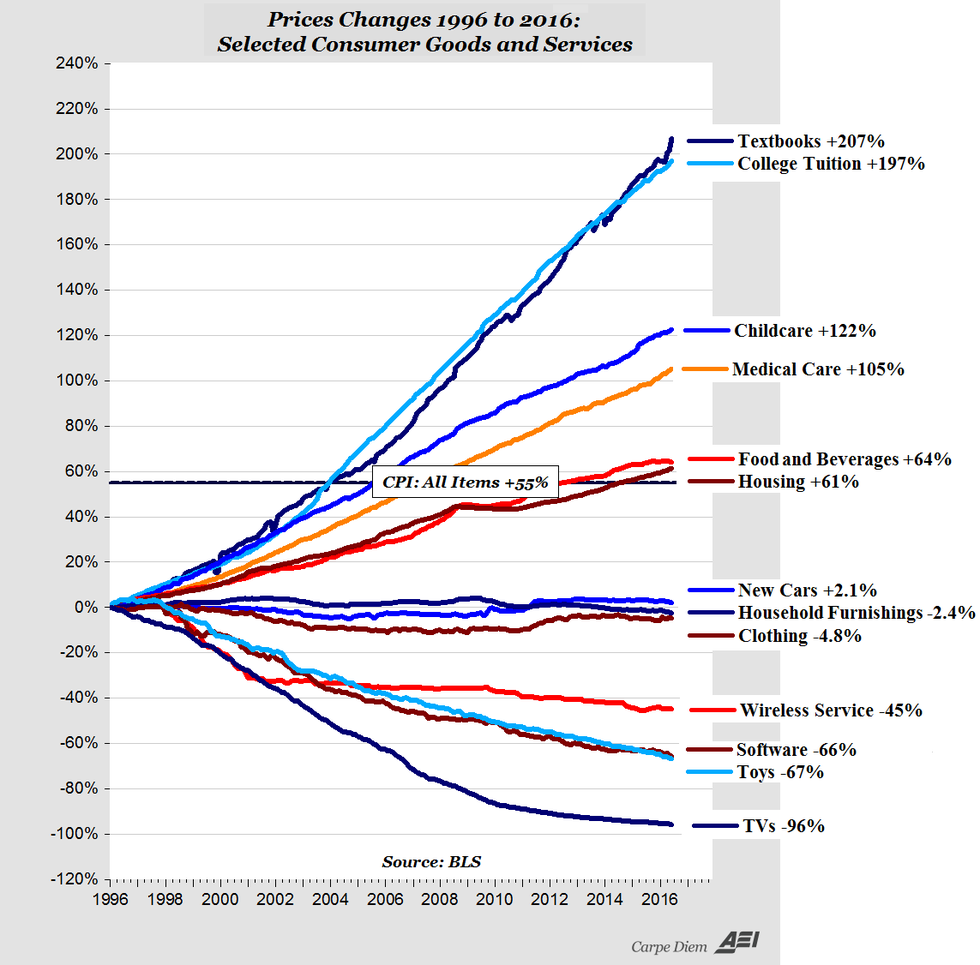

The growth in textbook prices in the past three decades is paradoxical. In a normal ecosystem for goods, the costs of producing goods in a competitive market decrease or remain stable over time because of new technologies. This explains why the costs of novels, cars, films, and furniture have decreased in the past decade. But the exact opposite is true for textbooks.

Intuitively, one would also expect the costs of books for subjects such as languages, algebra, biology, and history -- disciplines which are not regularly updated-- to remain stable. Yet again, that is not the case. For example, The french introductory level Bravo! costs $230 and Stewart . It is unconvincing that much has evolved in the world of French grammar -- unless the 8th edition was updated to include “Le Snapchat” or “Face-de-book” in its vocabulary list.

Perhaps the costs of producing, marketing, and author royalties are simply being passed onto the consumer. This is only partially true. When a former publisher did his own calculation, he found that it costs only $10 to print and $130 to pay authors and market an 800-page textbook, which is then sold for $180 to a poor student. The rest - $40 - goes toward company profits. That’s a 20% margin.

The explanation for such phenomena is oftentimes left up to speculation. And given the reasons for rocketing textbook prices (i.e., undue and constant revisions, software and workbook bundling, and so on), they fall into one textbook definition[1] of an economic idea: oligopoly power.

In a healthy competitive market, firms are able to compete prices to maximize revenue. The lower the cost of a good, the more customers it attracts. For the textbook industry, however, this is not the case. The big three publishers -- Pearson, McGraw Hill, and Houghton have little incentive to compete for lower cost products. They can co-operate to manipulate book prices (and they have!) with immunity from market forces.

Worse, the publishers will resort to excessive rent-seeking behavior to rule out any potential competitors and attempt to sabotage the used-books market. This means that the companies would indulge university departments and college professors with free copies and offers to publish their own books, as one GW professor describes. Professors are notorious for being unaware of the cost -- or even quality -- of the textbooks they assign yet oftentimes require students to purchase new and software-bundled editions. This sort of lobbying exploits professors’ knowledge gaps and strips students of their right to choose.

Students have created backlash against the industry with calls for open-textbook use in class. But an effective movement would entail innovation and systemic change to the demand of books. University departments and faculty must also ally themselves with students and allow for open-textbook usage. Not only will publishers will have to adjust their business model to finally lower book prices, but this creates an ecosystem that allows for new entrants into the industry -- such as an "Uber for textbooks."

Regarding numbers once more. There is another one of significance: 1. That's it, 1 university system in 1 state is what it takes to disrupt the status quo.

[1] Pun Intended

sunrise

StableDiffusion

sunrise

StableDiffusion

bonfire friends

StableDiffusion

bonfire friends

StableDiffusion

sadness

StableDiffusion

sadness

StableDiffusion

purple skies

StableDiffusion

purple skies

StableDiffusion

true love

StableDiffusion

true love

StableDiffusion

My Cheerleader

StableDiffusion

My Cheerleader

StableDiffusion

womans transformation to happiness and love

StableDiffusion

womans transformation to happiness and love

StableDiffusion

future life together of adventures

StableDiffusion

future life together of adventures

StableDiffusion