The summer between my sophomore and junior years of high school, I went on a church trip to Alabama, and my youth group volunteered at a women’s shelter with another church from Illinois. Surprisingly, the people from this other church never met anyone with Native American ancestry. Being a member of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, I enthusiastically told them about all the different tribes and nations in Oklahoma... until an unceremonious interruption from a boy in my youth group.

“Don’t be fooled,” he began. “He’s just saying he’s Native because he gets benefits."

I was completely outraged! I couldn't believe someone said such a thing! Yet, in the moment, I was speechless.

Thankfully, the lady whom I spoke to before simply shrugged off the boy's comment and wanted to know more about Native life and culture in Oklahoma, but embarrassment suddenly clouded my charisma, and I couldn't figure out what to say next.

Pow-Wow Dancers at the Choctaw Nation Labor Day Festival, Tushkahoma, Okla. Photo: Wyatt Stanford.

As I grew up, my mother always stressed the importance of our Native American heritage. I was always happy telling people about my pride as one-sixteenth Choctaw and Chickasaw. Often times, I got funny looks or people said, “You don’t look Native American to me” because of my fair complexion and blue eyes, but why does my appearance make pride in my Native American heritage so wrong?

Regardless, I finally realized why pride in my ancestry is not only an important passion; it is a necessity.

Several generations ago, my ancestors walked from Mississippi to Oklahoma on the Trail of Tears. They made it, obviously, and thus, here I am. However, it took many sacrifices along the way, and thousands died during relocation. When I say being Choctaw and Chickasaw makes me proud, I honor those who gave up so much just to live, those lost, and those who through all odds, made it to Indian Territory.

Although I am not full-blood Native American, my blood quantum doesn’t matter and shouldn't matter. Some full-blood Native Americans live completely outside of our culture, and some quarter-bloods still carry on traditional practices in traditional places. Despite these things, it is imperative we, descendants of our Native ancestors, carry on our culture.

During my first semester of school at Eastern Oklahoma State College (Go Mountaineers!), I enrolled in a Honors Humanities course to fulfill one of my Honors Program requirements. As students in the course, "The Arts and Social Change," we examined various types of art and discussed how artists affected change in society. Our final project required our creation of a piece (play, painting, interpretive dance, etc.) inspiring change. I thought about this project all semester, and I planned on creating something responding to student debt in America.

The week before project presentations, I started brainstorming ideas, but my mind went blank.

My heart was so set on this idea. Yet, after some serious thinking, I decided my chosen subject matter wasn’t speaking to me like I thought it did. My feelings about student debt didn’t run deep enough.

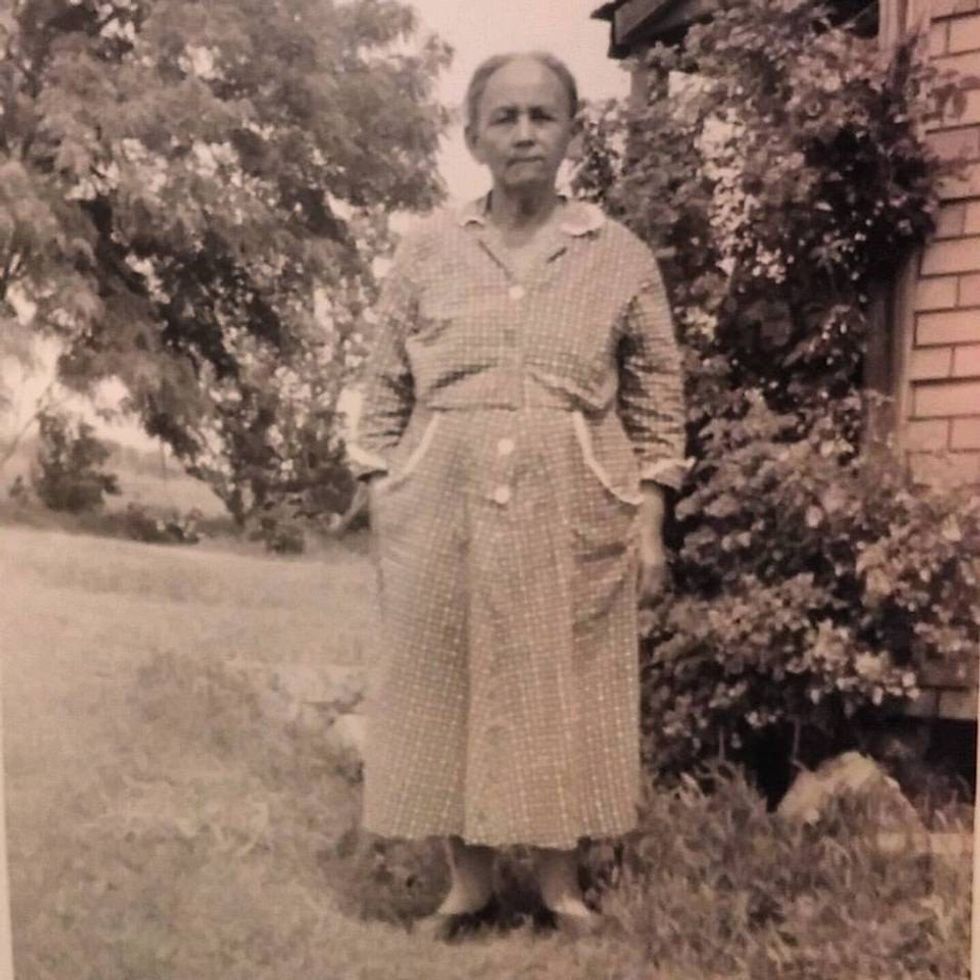

Taking a break from brainstorming, I cleared my mind and walked into my mother’s bedroom. She scattered things hither and thither looking for something, but on the bed was an opened picture box. The picture on top was a small, black and white snapshot of my great-great grandmother, Ida May Carter, my last full-blooded Native American ancestor.

Ida Carter, June 1957.

"That’s it!" I thought. "I need something involving my Native heritage... Why didn’t I think this before?"

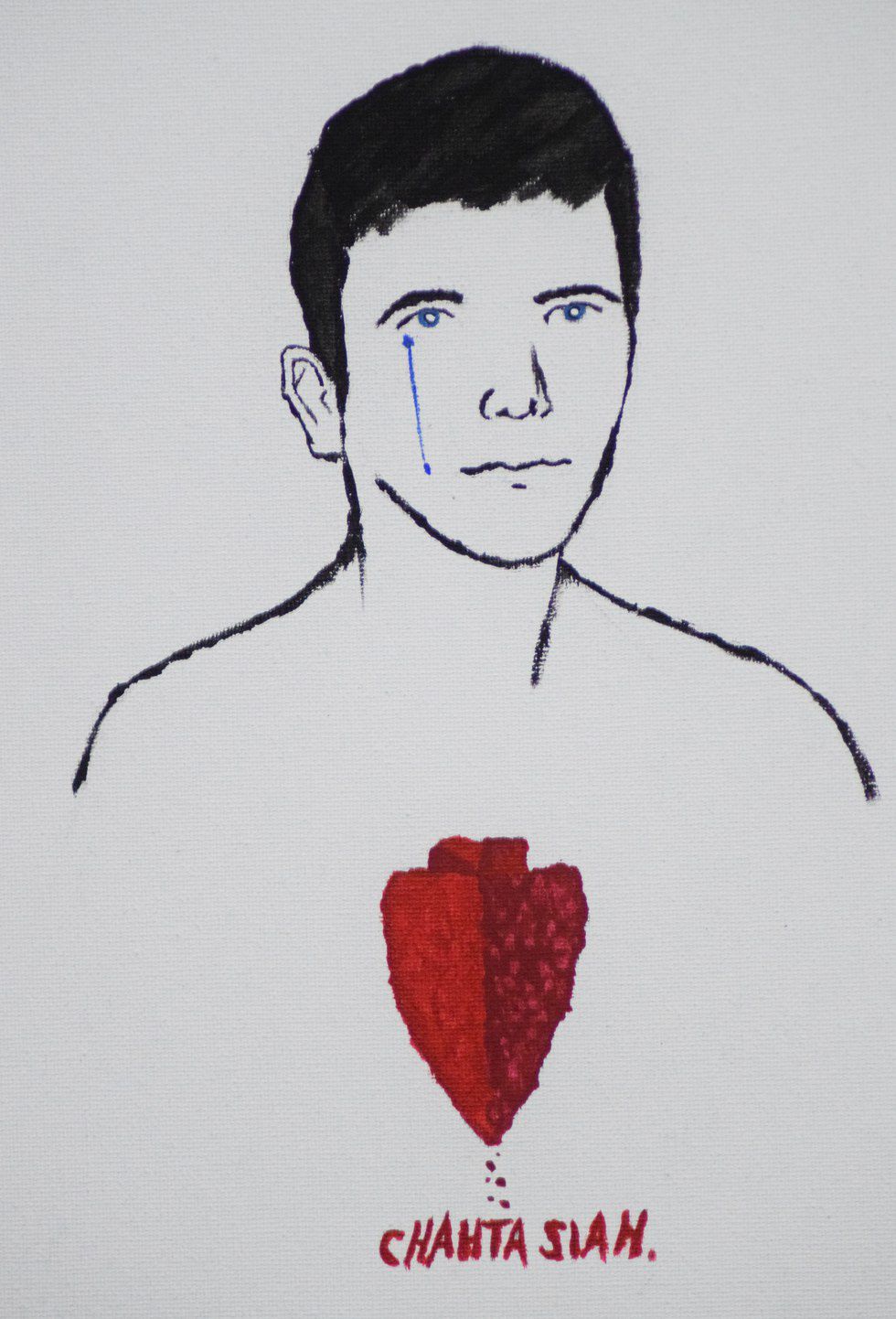

I drafted my compulsory artist statement and checked it repeatedly until I knew it word for word. I crafted a simple self-portrait with heavy symbolism as my final course project, and I was ready to present.

My turn came the first day of presentations. Everyone before me did such amazing work, and I was so nervous. One of my friends designed an outstanding video over the importance of feminism, another made a collage over body shaming, and I hoped my simple painting was just as powerful.

I made my way to the front of the drafty classroom and set the 11 x 14 canvas on the little easel I found in the back of a craft box my mother had in storage. After a deep breath, I began my presentation.

My Self-Portrait for "The Arts and Social Change", 'Portrait of a Modern Native American'

"The blank, white canvas represents my pale skin, my blue eyes, and a small tear represents my ancestors on the Trail of Tears, now seeming like a distant memory. My heart, full of Native pride, dripping the few drops of my Native blood. “I am Choctaw” written in Choctaw with some of the blood." I also spoke about how people quickly judge 'Native-American-ness', and then I ended the presentation stating how important it is continuing Native American culture and practices into the future amid such adversity in the 21st century.

My piece generated much discussion. One of my classmates mentioned his similar negative experiences in the work field, and then another classmate told me outright I changed his viewpoint. He said before my presentation, he completely dismissed people, like me, who said they were Native American and didn’t look the part.

After class, my instructor said I stole the show. I was so proud, and I felt my ancestors were proud, too. Through that project, I discovered why my heritage is so important to me. Not saying "I'm Native American" is like not speaking up for my forefathers and foremothers. Not saying "I'm Native American" allows the uniqueness of my Native cultures to disappear from this earth entirely.

"Chahta sia hoke!" Yes, I am Choctaw!

Yes, I am Native American.

I will always say I am Native American.

Grand Entry, Choctaw Nation Labor Day Festival Pow-Wow, Tushkahoma, Okla. Photo: Wyatt Stanford