Every time a mass shooting breaks out in the United States, it seems that the discussion that follows treads the same old ground—the question of causation. Blame the firearms? Blame mental health? Blame the media? This question stymies any progress on the gun control debate. However, a country with a similar culture and history provides the probable answer—Australia.

The Land Down Under has a history that seems to take pages straight out of a U.S. history textbook. From the moment the British citizens of the First Fleet landed in Botany Bay in 1787 to found the first European settlement in Australia—a moment as iconic as the landing of the Mayflower in Cape Cod—they came into conflict with the local indigenous people. Over disputes of game, property, and livestock, the European settlers made extensive use of firearms to fight off attacks by the Aborigines. In true colonial fashion, they massacred Aboriginal groups with superior firepower. With the unexplored portions of Australia serving as their equivalent of the American Frontier, the settlers had relied on their guns to protect them.

In 1854, gold miners in Victoria took up guns against the government in a spectacular battle (of only 15 minutes) known as the Eureka Rebellion. And in the process, they indirectly set the foundation for the birth of democracy in Australia. It’s a long story, but Australians have looked back upon the moment as the closest thing they had to a revolution like that of the American War of Independence. So, firearms figure prominently in Australian culture as they do in American culture—but no constitutional right to bear arms.

And with a history like that, Australians were known to embrace firearms. Surveys by NewsPoll in 1996 put the number of gun owners over 18 in Australia at 1.3 million in a population of just 18.3 million. Research by the Commonwealth in the same year found that 10 percent of Australians owned a firearm. 16 percent lived in households which contained a firearm. In comparison, in the U.S., three in ten U.S. adults own a gun, and 36 percent are open to own a gun in the future, according to a Pew Research Center survey in June 2017. And like the gun–loving U.S., Australia had its share of mass shootings.

A spree of shootings, both gang violence and lone shooter incidents, broke out in the 1980s. Motorcycle gang violence in Sydney, 1984, led to the Milperra massacre, which left 7 dead and 28 injured. In Victoria, 1987, lone shooters caused the Hoddle Street massacre, which left 7 dead and 19 injured, and the Queen Street massacre, which left 9 dead and 5 injured. The affected states implemented minor gun control measures to tackle the issue, but the mass shootings continued intermittently into the 1990s. Despite the outcry, the government responded tepidly, leaving the issue unresolved.

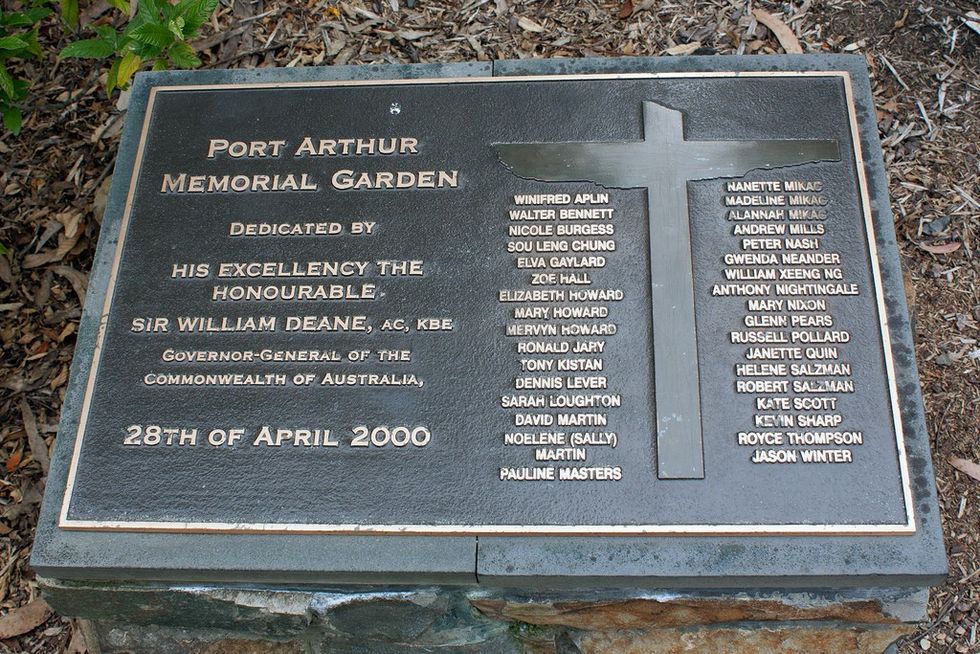

The Port Arthur massacre was the watershed in Australia’s history of gun control. A lone shooter with a semi–automatic carbine and a battle rifle killed 35 and injured 24 in Tasmania, April 28–29, 1996. And the government, including both the reigning Liberal–National Coalition and the oppositional Labor Party, did something highly unusual in Australian politics—they worked together in decisive and rapid manner. Prime Minister John Howard introduced strict gun control laws and devised the National Firearms Agreement. Only 12 days after the massacre, the state governments passed the laws necessary to put the agreement into effect. It restricted the private ownership of semi–automatic rifles, semi–automatic shotguns, and pump–action shotguns; it introduced uniform firearms licensing; it included a gun buy–back provision that would play a big role in mollifying Australia’s gun culture.

All of these national measures received widespread support, from the cities to the rural areas. Still, a few gun owners attempted to join the Liberal Party to influence the government, but they were denied membership. The Attorney–General Department stated that the Commonwealth Government would set the costs of buy–back measure and the setup of new licensing and registration systems across the States and Territories. The government spent millions on a public education campaign on the new gun control laws, upgrades for police information systems, firearm basic training programs, and buy–back funds, all of which were paid for with an increased Medicare levy. In time, the temporary gun buy–back program took around 650,000 assault weapons out of civilian hands—one–sixth of the national stock.

But now that the guns were regulated, did the mass shootings cease?

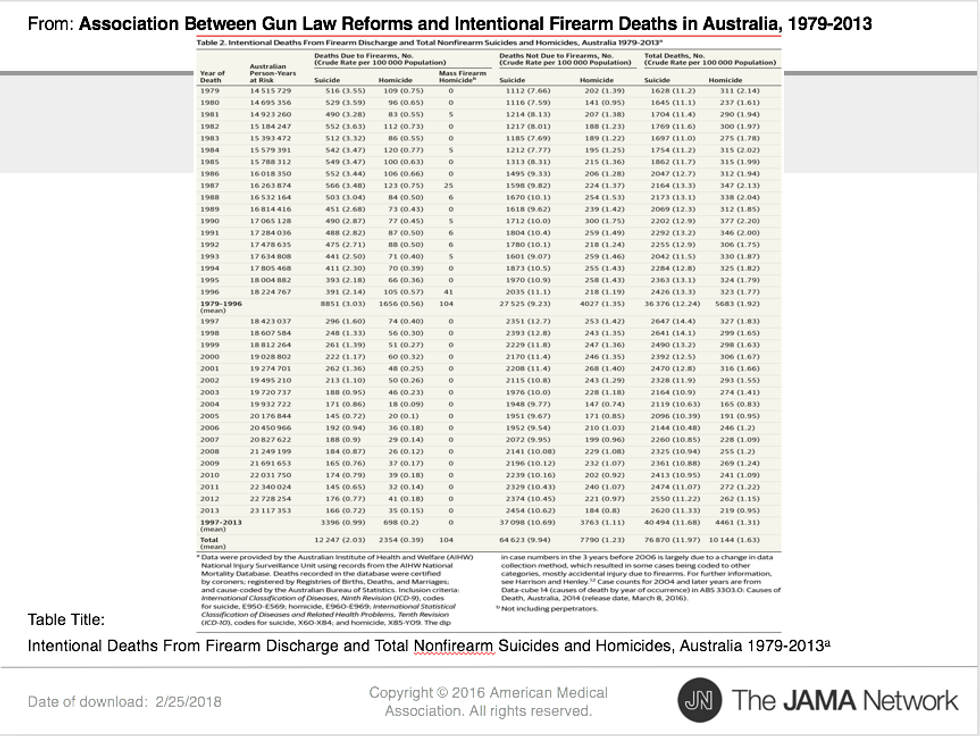

Well, there were certainly less mass shootings. A June 2016 study by the School of Public Health in the University of Sydney found that in the years 1979–1996, 13 mass shootings occurred (the criteria is higher in Australia at 5 victims or more than in the U.S. at 4 or more) with 104 killed and 52 wounded. In the years 1997–2016, after the Port Arthur massacre and bans, no mass shootings (by definition) occurred. The data is more convincing in terms of overall deaths due to firearms, which declined from a mean annual rate of 3.6 people per 100,000 in 1979–1996 to a rate of 1.2 per 100,000 in 1997–2013. Meanwhile, the mean annual rate of total non–firearm suicide and homicide deaths in the same periods increased only from 10.6 people per 100,000 to 11.8 per 100,000. Gun–related deaths fell sharply after the gun control measures were put in place. The causation is clear.

By this precedent, at least, we have evidence that suggests that increased gun control lowers the rate of homicides and suicides by firearms. This is the case for other nations like Norway, Canada, and the United Kingdom, but the case of Australia is especially important to examine because of the similarities in their gun cultures and histories. Of course, the U.S. has a larger population, a bigger national stock of guns, and an absurdly strong gun lobby, but it’s certain that the proliferation of firearms is chiefly to blame for the proliferation of mass shootings.