Some context for this article first: growing up, I was a big Linkin Park fan. After years of my music taste being determined mostly by what my parents listened to, Linkin Park was the first band that I felt like I had found for myself. Linkin Park appealed to me because they sang about anxiety, fear, sadness, frustration and difficulty dealing with life in a genuine way that made me feel like I had a rock band that really cared about me. Linkin Park's lead singer Chester Bennington was a huge part of why the band connected with me so much. Not only did he have one of the most technically incredible voices in rock in the 2000s, his lyrics were always fascinating and comforting to me. As an angsty, often lonely kid, Chester helped me a lot. As time went on, my music taste grew and changed as I did. I didn't listen to Linkin Park as much anymore, but I still loved their songs when I heard them, and appreciated the efforts the band made to be open about sadness and depression and to make the world better.

On July 20, 2017, while I was on break at work, I learned that Chester Bennington had taken his own life. I was absolutely distraught. Throughout 2016 and into 2017, there had been many high-profile celebrity deaths, but this one was different for me. Chester had been one of my favorite singers and someone I greatly admired. I understand that mourning celebrities can sometimes be a bit shallow; after all, I never actually got the chance to meet Chester, and I didn't really know him. But that's the thing about great artists: you don't grow attached to them because you know them, you grow attached to them because you feel like they know you.

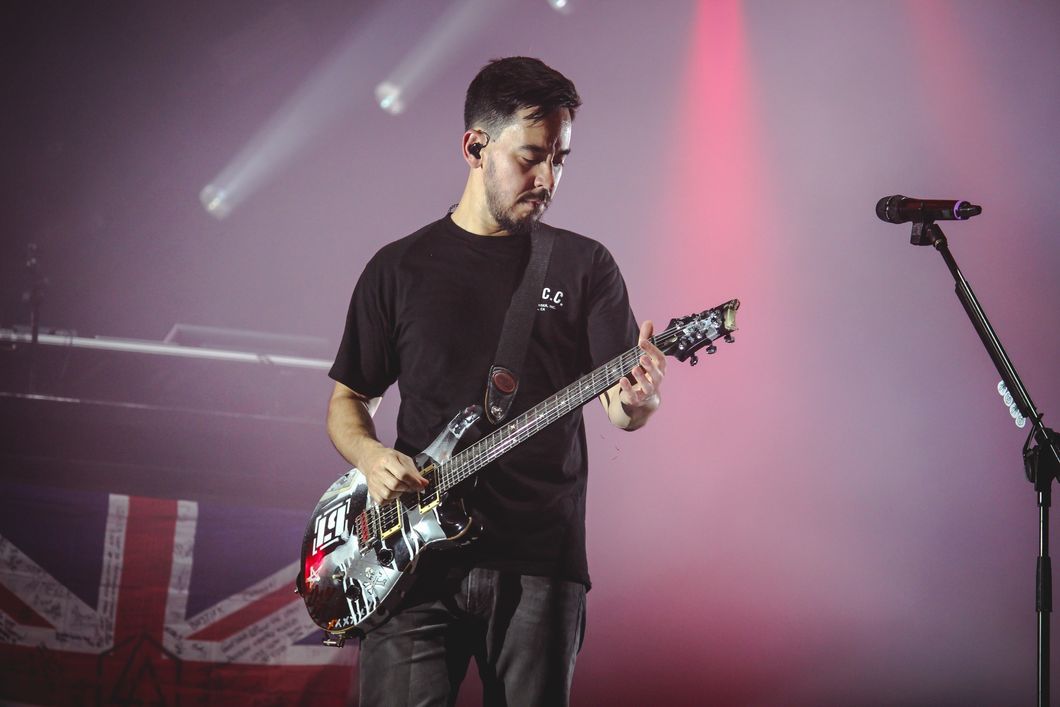

It's been almost a full year since Chester's death. I still listen to Linkin Park's music, but it's a little bit harder now. On June 15, 2018, Linkin Park's other frontman and Chester's close friend Mike Shinoda released an album called "Post Traumatic." Judging by the name, I had a feeling that this album would deal heavily with Chester's death. With a bit of hesitation, I decided to give it a listen, and I gotta be honest, my brain has been left a little bit broken.

It's important to a lot of music critics that an album has the ability to stand on its own as a piece of entertainment, to be of good quality when you separate it from the context in which it was written. While oftentimes I agree with that idea, every now and then an album comes along that I do not think should be separated from its real world context. David Bowie's "Blackstar" is like that. Kendrick Lamar's "To Pimp a Butterfly" is like that. Mike Shinoda's "Post Traumatic" is also like that.

Now, I'm not gonna draw any comparisons of quality between those other albums and "Post Traumatic." If we're looking at this album strictly from how musically innovative or lyrically complex this album is, it's average. But that's not what I want to say about this album. If you're looking for a traditional review, go to Pitchfork or Allmusic, where complex creatives works can get slapped with a quick and easy "3 out of 5 stars" and be quickly forgotten about.

What I realized about Post Traumatic is that it is essentially Mike Shinoda's step-by-step healing process in album form. In my opinion, the album can be split into two halves. The first half is extremely devoid of optimism and is most likely set in the early stages of Mike's grieving process. The healing has not yet begun, and Mike is still dealing with the immediate consequences of losing his friend and the singer in his band. While Shinoda's depression following the death of his friend is of course discussed, Shinoda addresses another important aspect of the context surrounding the album: the expectation for musicians to sell their pain as an entertainment product. This is something that was on my mind during the release of Linkin Park's 2017 album "One More Light." Like much of Linkin Park's previous work, the album dealt with themes of depression and grief, but was not well received by music critics. Much like "Post Traumatic," if the album is simply taken as a piece of entertainment, it's completely average. But then Chester committed suicide, and it became clear that this completely average album was written from a dark place in a mind that was losing the fight with depression.

There's an unfathomable amount of music available to us today, and a lot of it discusses depression, grief and anxiety. That's not a bad thing; in fact, it's a great thing. Great music, and great art in general, often springs forth from an artist's deepest, darkest, most complex emotions, and the fact that so many artists choose to bare their souls to the world through their art is a gift. I think this sheer quantity is the reason that people who listen to music critically forget the real nature of art. Art is neither entertainment nor real life; it is both.

"Post Traumatic" is a grieving process in the form of music, and it shouldn't really matter if that grieving process is "musically innovative" or not. Mike Shinoda had no responsibility to share his process with the public, but he chose to. This choice probably did not stem from a desire for critical acclaim. Mike Shinoda knew that Linkin Park fans needed closure over Chester's death, and he knew that he might be able to help. That's why I can't review this album. Because I don't think it's right to review someone's healing process just because it has been published in the form of entertainment. All I can do is tell you whether or not I recommend it. Which I do, wholeheartedly. Not because it is great piece of entertainment, but because it is real life.