“A cemetery, a surprise, and a death camp,” tour guide Rabbi Yitzhak said, reciting the day’s itinerary at a cheery 7:45am.

A 4 hour long drive took us to a cemetery in Lodz (pronounced Wodge). There, we first learned about how to bury a Jewish person, from pouring water on the body to burying it as soon as possible; dead bodies must be respected. We then learned of an instance in which this was definitely not the case. Rabbi Yitzhak told us of a guy who was preparing a dead body for burial and smoking. When he needed to put down the cigarette and use both hands for his job, he stuck the cigarette IN THE DEAD PERSON’S MOUTH! My own mouth hung open at this and shocked can't even begin to convey my anger at this disrespect.

We then toured the cemetery, and as uncomfortable as this might seem, I really thought that the cemetery was beautiful. We saw some ridiculously exquisite pre-Holocaust graves including this massive memorial.

It was built for a wealthy man, Poznanski, who had so much money that he could afford to line the entrance to his house with gold coins. He and his wife were buried in it, the grave more than large enough for them both. And while this might have been the most elaborate grave, it was not the only beautifully adorned grave; the cemetery was full of them.

Next, we went to a church in the Lodz ghetto and examined a sewer outside of it. Chaim Rumkowsky, the Jewish leader of the ghetto, wanted it to become its own entity. He established currency strictly to be used in the ghetto, and he designed the sewers with Jewish stars on them.

However, Rumkowsky was power-hungry and controlling, and he went too far. He was unfair in his portioning of food, and when the Nazis asked for 1000 people to be sent to Chelmno, a death camp, he selected children for the slaughter. Fortunately, the Russians liberated Lodz, and Rumkowsky was sent to the death. Rumkowsky’s story showed me that violence wasn't just Nazis on Jews (and other groups); it was sometimes Jew on Jew.

After one more stop, we went to our surprise! Walking along the years of our history, we arrived at a cattle car.

Darkness washed over me as I entered, and the pain of the Holocaust pierced the air in the close quarters. Rabbi Yitzhak told us stories of people jumping out of windows to escape the cattle car and sharing a single bin as a toilet, the stench spreading across the car. He shared stories of women who gave birth in the cattle car and of moms and babies dying in the process.

We were shivering from the cold and the horrors, but the next few moments rewrote history and made us smile.

Rabbi Yitzhak told us that we were going to do something in the cattle car that had never been done before, and he invited WashU Rabbi Lazarus to speak. Rabbi Lazarus spoke about one of our madrichot, Maddie. He said the words that we all knew about our sweet and soulful madricha: she is kind, thoughtful, and brings joy to all of those around her. Though there are some uncertainties in her life, Maddie is committed to finding and doing the things that are meaningful to her and to helping others do the same via yoga, meditation, and conversation. He told us that Maddie wanted to be officially given a Hebrew name and she chose Maya as her name.

As Rabbi Lazarus declared her Hebrew name Maya, we witnessed the joy of a rebirth. All of the girls held hands in a circle and danced to celebrate the simcha (joyous occasion). I noticed a beam of light radiating from the window and looked into Maddie’s eyes. She really, truly was happy, and I could tell that something new and beautiful was born inside of her.

Knowing all of the pain of the past, we were able to add some joy to the history of the cattle car, for despite all of the sorrows that have befallen the Jews, we always have the power and strength to rise above and to search for our truest selves. With her new Hebrew name, I know that Maya will be able to do just this, and I'm so grateful to have had shared such a meaningful experience with her that brought into the darkness the light of a better future.

As the light faded, we went to the death camp Chelmno. We walked through sand to find grassy patches and rectangular areas filled with small rocks awaiting us.

Our experience at this death camp was different from that of Majdanek and Auschwitz I/II, for instead of listening to lengthy speeches about history, we took action in the present.

Rabbi Yitzhak instructed us to search for small bone fragments in the open fields. I walked around the patches of grass, finding several white bits that were smooth on one side and more porous on the other, which I identified as small bones.

I returned with my findings to where Rabbi Yitzhak was standing and he took them from my hand. Other students placed theirs into his hand, too, and when he had received all of the bone fragments, he lifted up some of the small rocks in a rectangular area to reveal soil. He carefully placed the bone fragments in a depression in the soil and covered them up, finishing the burial by putting rocks back on top of the soil.

These bone fragments have been lying, unburied, in the grass at Chelmno for 72 years. Eroding, exposed, empty.

With a funeral for the bone fragments, my group was finally able to return these human parts back to the earth, to mourn for the losses in the Holocaust, and to treat the dead with the utmost respect. We made a circle near the buried bones and said Kaddish (a mourning prayer), sang Hatikvah (amongst other songs), and gave our hearts and our souls and our voices to the darkness of the vacant field.

As we left Chelmno, I saw written in the sand the words: WE ARE STILL HERE.

Through all of the Jews’ twisted history, from mass murders and deadly childbirths to endless wandering from land to land, from conflicts with other peoples and within our own to celebration of our culture and customs, and from brises and B’nai Mitzvot and weddings to parents giving up their children to non-Jewish parents out of pure love, the stories of our past reveal our unswerving will to survive. We are still here and we always will be.

I kneeled and drew a heart in the sand at the entrance to the death camp. Looking back at the field, I caught a final glimpse of the rocks covering the now-buried bone fragments. I could still hear our voices ringing in my head, piercing the heavy silence and bringing to the death camp nothing but life and love.

My own heart heavy and full, I rose from the heart in the sand and walked away, leaving my footprints and my undying love behind.

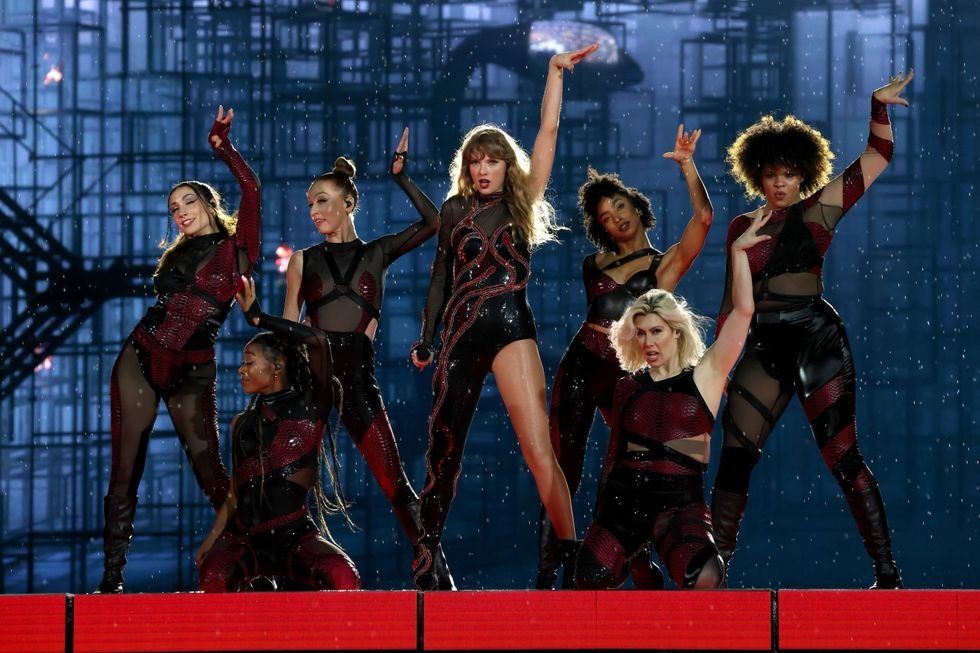

Energetic dance performance under the spotlight.

Energetic dance performance under the spotlight. Taylor Swift in a purple coat, captivating the crowd on stage.

Taylor Swift in a purple coat, captivating the crowd on stage. Taylor Swift shines on stage in a sparkling outfit and boots.

Taylor Swift shines on stage in a sparkling outfit and boots. Taylor Swift and Phoebe Bridgers sharing a joyful duet on stage.

Taylor Swift and Phoebe Bridgers sharing a joyful duet on stage.