Today was an early wake-up. There is so much we must see and do and learn in Poland, and it must be all packed into a few short days.

We boarded the bus, bundled up in layers of clothing and clutching bags of bread for breakfast and lunch, and we tried to mentally prepare ourselves for the day, but it was no use. There is no preparation for seeing a death camp.

As the bus began to move, my friend looked out the window and said, "I have never seen something so gray in my life."

He was right.

The sky was painted gray and the haze clouded all of the buildings and people and land in Poland. It was as if we were still stuck in the 1940s, nearly 80 years behind the present and unable to move on from the horrors of the past.

Our first stop of the day was at a Yeshiva in Lublin.

There, Rabbi Yitzhak and Rabbi Trepp, two of the trip leaders, told us stories about Jews during the time of the Holocaust, and what really struck me was the strength of the Jewish spirit. Although the Nazis tried to kill the Jews’ bodies, they could not kill their souls. The Rabbis told us that some Jews even sang as they were going to the camps or being shot. They sang old songs from the past and came up with new songs and chants, such as one in Yiddish which translates to “We will outlive you.” This, being chanted at the Nazis, is a testament to the resilience of the Jewish culture and soul, for both will last as long as Jewish people shall live.

We next rode to Majdanek, which is a death camp in Lublin. There are three types of camps: concentration, labor, and death. Death camps are the ones with gas chambers. Majdanek initially was not a death camp and was rather a place where Jews were dumped and forced to sort out other Jews’ belongings from the other camps. Evilly strategic, the Nazis cleverly coerced the Jews into the camps by telling them that they were just being relocated. This caused the Jews to bring all of their most valuable belongings to the camps, which the Nazis then stole.

Life was hard in Majdanek. We were assured of this right when we walked into the camp. We first started down a slippery slope and then struggled up the stairs that followed until we reached a huge, jagged rock. With the rock, symbolizing the burden of the weight of the Holocaust and the struggle for a future, suspended above two cylindrical rocks, my group was able to freely walk under it. It was not so easy for Jews during the Holocaust to do the same.

After entering into Majdanek, however, things only got worse for these Jews. All of their possessions were taken from them, even their shoes. After cutting the soles out of the shoes and searching them for hidden valuables, the Germans piled the shoes into metal storage nets.

An interesting fact that Rabbi Yitzhak pointed out is that people’s feet mold the shoes they wear and leave an imprint on them. Like their shoes, each of these Jews has left an imprint on the lives, memories, and hearts of their loved ones and of the people who strive to remember them today.

They were then stripped naked, their heads were shaved by other Jews, they were washed, and then they were given light clothing, almost like pajamas, to wear in the freezing Polish weather. The ones who lived, at least. Once Majdanek became a death camp in the early 1940s, the Jews faced an even more grim fate.

20,000 Jews were gassed in Majdanek. They took a life-ending shower. And even in the bleakest situation, some Jews still managed to cling to their loved ones and to pray.

My group sang the Shema (a prayer for God to hear the Jews) in their honor, and our prayer echoed through the gas chambers. It was a cry for our history and a defiant strength to remember it forever.

After looking at several rooms filled with shoes and bunks, we went to the Russian memorial.

The dome opened to reveal a massive mound of what looked like dirt underneath. It was shocking to me that after nearly 80 years, the dirt was still there! Yet the reason for its longevity is because the pile was not of dirt. It was rather a blend of cremated human bodies and feces. The Germans combined life and waste to further degrade the Jews. In life, the Germans were upset at the Jews because they accused them of acting like they were above morality. So in the Holocaust, and especially in death, they treated the Jews like complete and total waste, putting them below morality and showing them the ultimate disrespect.

Lastly, we stopped at the crematorium. This was for the people who were not gassed, which was over 50,000 Jews, who died of various causes in the camp including cold, starvation, and being overworked. After seeing the weight of the waste in the Russian memorial, we were able to see the means for it, which shocked us into the realization of the terrors in our own history. Gathering together, we sang the Israeli national anthem, Hatikvah (hope), as a prayer for the Jews who died in the Holocaust and as a desire for a better tomorrow. It dawned on me that it is our right and responsibility to carry on the stories of the past so that they will never be forgotten. We’re on this trip not just to see Holocaust sites, but to remember them and to pass on our history to our children and their descendants so that history will not repeat itself.

Our last site of the day was the coffin of Rabbi Noam Elimelech, the first Chassid. He strove to uplift people’s spirits, particularly those who were poor, and did so especially through song. This led to Lubavitch, and the rabbi’s work is still extremely present in Judaism today. At his coffin, we first prayed and then sang a tune over Vodka (I didn’t drink any; I promise, Mom!) in the hope of uplifting people’s spirits after such a heavy day.

I am going to bed feeling hope and sickness and strength churning in my heart and stomach and mind. I should have expected not to see clarity through the gray in Poland, but I don’t think that I anticipated having such conflicting feelings about the sites I’m seeing. I think this is a good thing though. History isn’t meant to be black-and-white, and my swirling thoughts give me a lot to process about the Holocaust.

Tomorrow, we are seeing Auschwitz. I’m predicting gray.

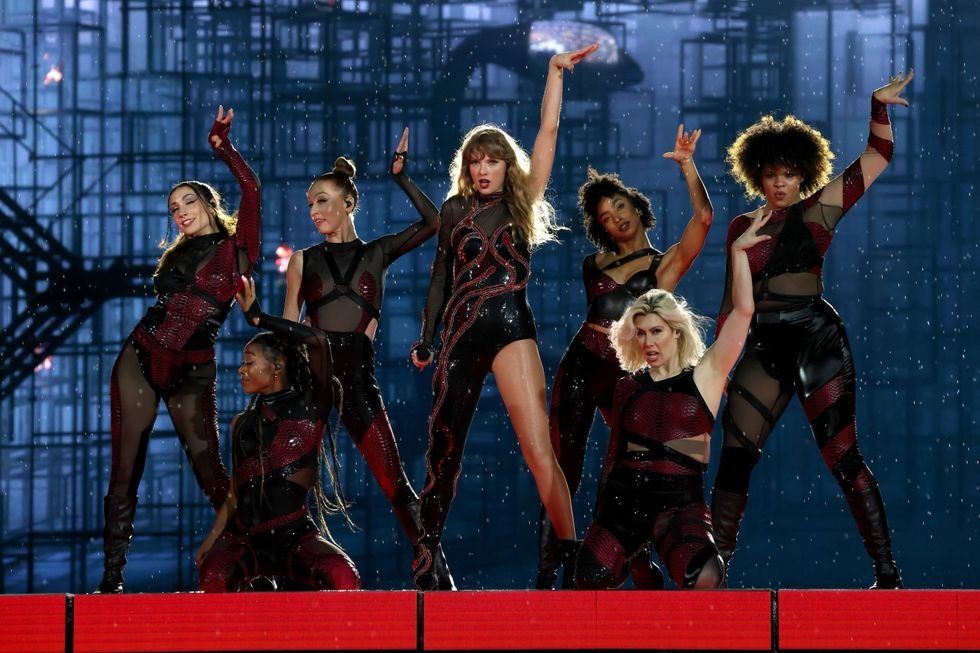

Energetic dance performance under the spotlight.

Energetic dance performance under the spotlight. Taylor Swift in a purple coat, captivating the crowd on stage.

Taylor Swift in a purple coat, captivating the crowd on stage. Taylor Swift shines on stage in a sparkling outfit and boots.

Taylor Swift shines on stage in a sparkling outfit and boots. Taylor Swift and Phoebe Bridgers sharing a joyful duet on stage.

Taylor Swift and Phoebe Bridgers sharing a joyful duet on stage.