Yogi Berra once said, “Baseball is 90% mental. The other half is physica.”

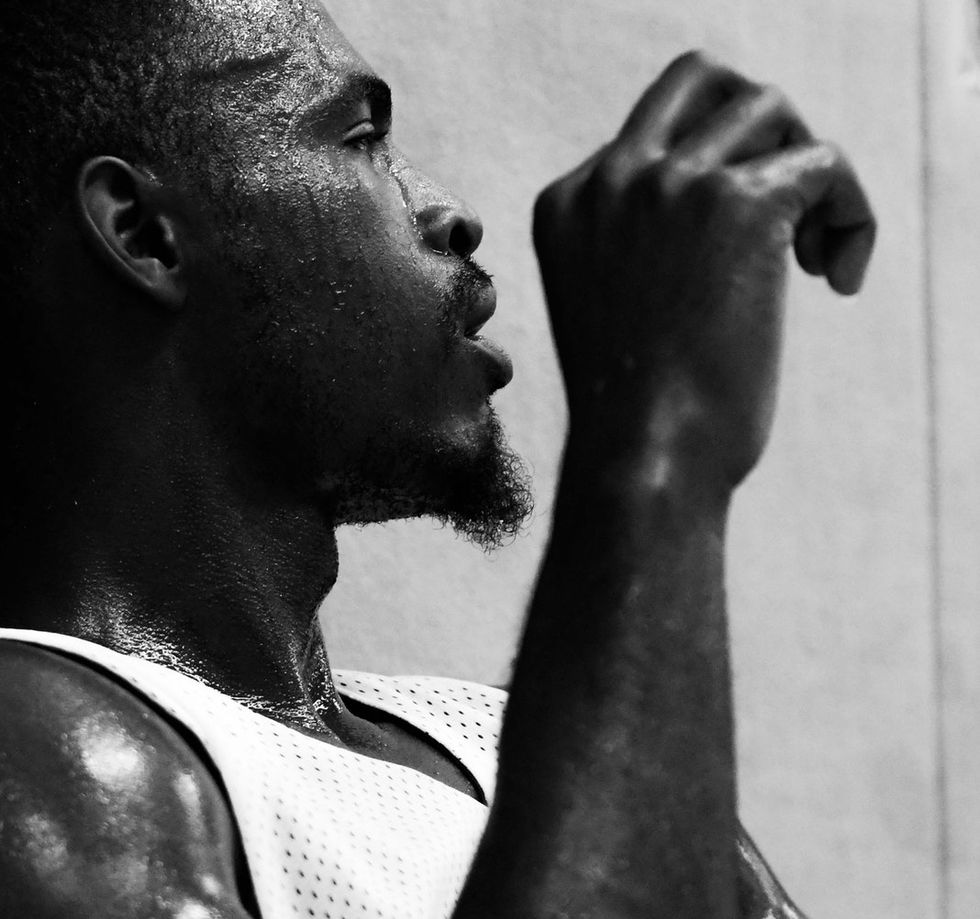

One could replace ‘baseball’ with any other sport and this quote would still reflect any elite athlete’s reality. They operate within an environment where performance and ability measure self-worth, coaches and teammates demand completely impenetrable toughness, and each pressure-filled moment can dictate one’s entire future. Although the general public, including their coaches and trainers, believes these collegiate competitors should maintain, without difficulty, resilient and confident attitudes regardless of their individual situation, the truth reveals a much different story.

According to a series of studies conducted in 2015, that would eventually catalyze the NCAA to perform its own research on the subject of mental health, 33% of student athletes identify as being 'depressed', 23% experience clinically relevant levels of depression, 26% feel a severe need to seek mental health services, 52% have consumed over 5 alcoholic drinks in one sitting more than once a semester, 22% have used illegal drugs as a coping mechanism, 12% have either eating or body image disorders, and almost 10% felt they needed some sort of suicide prevention resource[1].

While yes, college kids who aren’t members of varsity sports teams also often suffer from a plethora of mental disorders, student-athletes face an additional set of unique obstacles when it comes to pursuing assistance for symptoms of ‘non-physical’ illnesses.

A 2017 Ball State University study found that out of the 349 college athletes they surveyed from programs around the country, 54.3% of respondents felt they needed mental health intervention, but more than half of that 54.3% had never used the services available at their university (Moore). Despite both recognition by the athlete of their own internal struggling and the presence of some sort of counseling center or aid at the school, the victim's failure to seek-out (nor receive) help causes a significant and destructive impact on the individual’s future and overall life.

These student-athletes afflicted by mental health issues demonstrate reluctance in soliciting proper treatment because of the pressure on them to maintain a hardened and impenetrable disposition, the widespread taboo stigma associated with the reality of mental illness, and the difficulty to seek out help in a private manner.

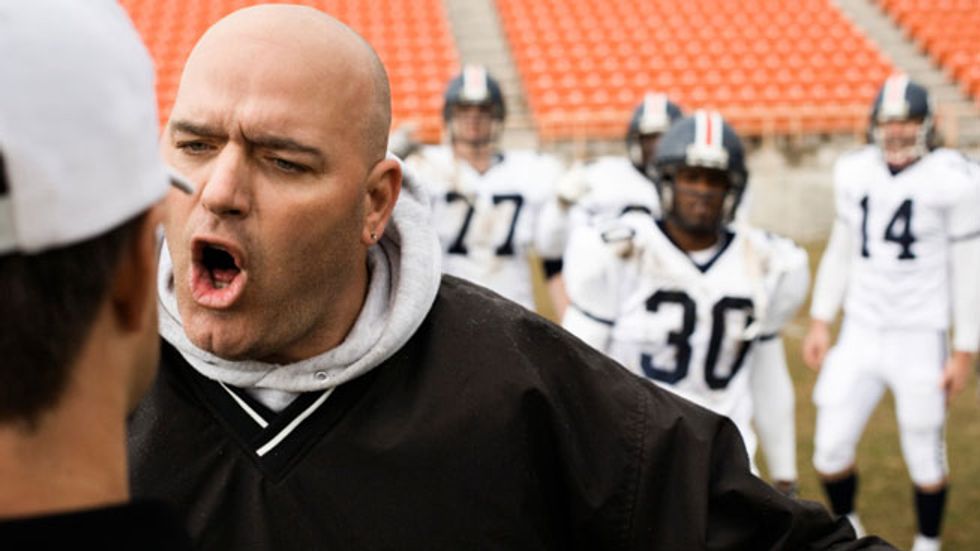

Coaches, parents, and trainers condition their athletes to practice mental toughness in all cognitive aspects of their game; however, by preaching this mantra, they neglect to account for the wide-ranging spectrum of what the psychological facet of sport encompasses, “from resiliency to mental disorders,” (Moore).

Players learn to “rub dirt in” their physical injuries and “suck it up” when it comes to anxiety, frustration, or disappointment. Respondents to the Ball State University report mentioned earlier cited both “feelings of weakness based on athlete identity” and “counter-production towards sports culture” as reasons for their hesitancy to search for help with their emotional and behavioral troubles (Moore). Society perpetuates a stereotype of hardened confidence and undeterred strength upon these athletes to such an extent that when they deviate from these standards they feel as though they betray their own identity as a competitor.

In the athletic community, weakness insinuates failure, and in a diegesis where failure determines a player’s prospective career, one would accordingly choose to hide their insecurities. Athletes fear, and rightfully so, the disapproval of their coaches, and strive to maintain the ideal reputation in the eyes of these figureheads of power.

Ball State University’s research initiative also explored the impact of an athlete’s division (1, 2, or 3) on their reluctance towards seeking treatment. The study found that D1 athletes were the least willing of those included in the survey to utilize their school’s mental health services, and accordingly that the D3 student-athletes were the most likely out of the selected group (Moore).

Division 1 programs typically accentuate the ‘athlete’ aspect of their student-athletes’ titles over their role as a human student of the university, and frequently hold their athletes to a greater standard of resilience, regardless of the more intense and competitive environment that accompanies the higher division designation.

Because the atmosphere generated by coaches and training staffs prioritizes athletic and academic success over behavioral and emotional stability, athletes lack the mental health knowledge to assess their own psychological states.

Generally, sports culture supports ignoring, pushing through, and not burdening others with individual distress as a safeguarded method for dealing with symptoms of conditions like depression, anxiety, eating disorders, substance abuse, or even suicidal ideation. Many programs under NCAA delegation do not educate their students on the importance or logistics of mental health and how it pertains to athletics, and instead replace these crucial lessons with ‘motivational’ talks about mental toughness and ‘fake-it-til-you-make-it positive attitudes’.

A study conducted by Dr. Laura Sudano and Dr. Christopher M. Miles in 2016 surveyed 173 different head athletic trainers at D1 NCAA schools about mental health care providers, their perception of care coordination, and screening for diagnosis at their respective institutions (Sudano, Miles). The results proved the researcher’s hypothesis that there exists “a great variability in resources and current practices and no 'standard of care' for mental health within NCAA athletic care facilities and programs” (Sudano, Miles).

Besides not mandating guidelines for care of athletes suffering with mental disorders or in need of emotional or behavioral support, the NCAA requires no baseline informative presentation or resources for athletes on the impact or presence of mental health disorders within their field. Teams institute a blanket philosophy of physical success over psychological concerns that universities not only condone but also facilitate by proliferating the image of the impervious athlete who can handle stress with unrealistic ease.

Another reason student athletes demonstrate an unwillingness to pursue treatment for their mental illnesses stems from the global misconception of ‘non-physical’ ailments. Mental health awareness is a growing national phenomenon, but many still reject its viability as a legitimate medical concern.

Earlier generations wrote mental afflictions off as the work of the devil, criminal behavior worthy of exile to an asylum, or most commonly, a desperate and pathetic cry for attention. While continuously advancing biomedical and psychological research disproves past theories, many people still today hold on to generalized myths about mental health and its victims.

Their misunderstanding and ignorance often arise from the inability to clearly parallel physical injuries from intangible ones. The diagnosis of a mental disorder requires a more abstract analysis process which can leave individuals wary towards the actuality of the results.

However, if a clinician/psychiatrist has the right materials and tools, they can almost always correctly identify their patient’s emotional or behavioral condition. Unfortunately, less than 43% of the athletic trainers surveyed in the Sudano and Miles study indicated they possessed the proper resources for mental illness (and that’s not even taking into consideration the less-funded Division 2 and 3 schools) (Sudano, Miles).

Athletic training programs have the necessary means to treat physical maladies, but they often lack the essentials to treat the over 1/3rd of their athletes suffering from mental disorders (JIIA). As former college cross-country runner Molly McNamara writes in the NCAA’s comprehensive report on the combination of mind and body within sport from 2014, “We don’t feel shame over having to go to physical therapy for a stress fracture – why should we feel any different about allowing time and treatment to heal anxiety or depression?” (Brown).

The shame she refers to emanates in part from the incapability of most athletic training departments to treat mental afflictions as compared to physical injuries. If an athlete’s administration and training branches refuse to take mental health seriously both financially and logistically, then an athlete will accordingly feel embarrassed and or hesitant to request help in that particular area of health.

The pervasive stigma attached to mental health also coincides with an athlete’s preconceived expectations towards how a training staff member, a coach, or even a psychological expert will respond.

Athletes frequently distrust coaches who introduce foreign mechanical methods or contradicting strategical viewpoints because they develop an attachment to whatever they’ve practiced most. They instinctively trust what’s most familiar to their ‘muscle memory’ (a phenomenon in the sports world in which a behavior becomes perfected and natural through continual repetition). In many cases, athletes would apply this doubtful mindset to something completely new like mental health therapy or treatment because it opposes the ‘mentally tough’ and physically-oriented outlook they’ve been acclimatized to (Lopez & Levy, 2013).

An athlete also might feel like a complaint about a cognitive agony may not be taken seriously or, arguably worse, may be unfixable. They might believe that a non-physical injury fails to compare to a classic physical ailment so therefore it does not warrant a rehab and recovery process of any kind.

Additionally, the Sudano and Miles report shows that part of the athlete’s dubiousness towards potential treatment derives from unqualified staff serving as mental health clinicians. Only 20.5% of their respondents confirmed they had a mental health provider working in their athletic training room.

Some answers as to what the credentials of the school’s current person in charge of counseling or mental health for athletes included: marriage and relationship therapist, clinical social worker, family therapist, and general psychiatrist (Sudano, Miles). Inappropriate staffing (which occurs when schools neglect the mental health aspect of sports) within the athletic training department, causes discomfort within an athlete seeking a reliable means of professional help.

One of the most common factors student-athletes listed as a deterrent from seeking out care in the Ball State University study, as well as the NCAA’s report, involves the individual’s concern towards privacy and discretion (Brown) (Moore).

Athletes fear that their association with the generally taboo domain of mental health could irrevocably tarnish their reputation and or opportunity for playing time. The pressure a coach imposes on his or her players to exhibit perfection both physically and mentally persuades team members to avoid ‘complaining’ about any existing anxiety, depression, self-loathing, or even suicidal thoughts. While a ‘normal’ counseling center perceives grievances from regular college-attendees of this unhealthy nature as serious and worthy of intervention, all too often these expressions of intrapersonal pain within the sports realm get brushed away as signs of weakness or petty grumbles.

A student-athlete may stray from receiving the help they need based solely off of the disclosure risk that comes with confessing their psychological suffering to an outside source. One athlete, who remains anonymous, wrote in the free response section on the Ball State survey, “I do not know who to talk to about my problems. I also do not want my coaches and teammates finding out I need help,” (Moore).

This student’s honest reply demonstrates first-hand the reality of college athletics and how their disregard of the seriousness of mental health causes victims to remain in silence. They observe inaction and taciturnity because they’re afraid that broken confidentiality could lead to their coaches or teammates (people who supposedly have their best interest in mind) discovering their ‘secrets’.

Because inconsistency seems to be the only standard of mental health treatment within the realm of collegiate athletics, student-athletes cannot understand the process holistically nor simply. Without the requisite knowledge of how one receives and undergoes care for mental health as a collegiate varsity sports participant, students approach pronouncing their intangible concerns with hesitation and uncertainty of their rights of privacy.

Aaron Taylor, a former All-American linebacker at Notre Dame, admitted to the NCAA for their study in 2016, years after his graduation, that, “beginning in college and throughout my professional career, I battled depression with the same regularity as blitzing defenses, but the external opponents were much easier to deal with than the internal ones,” (Brown). Throughout his testimony, Taylor reiterates that he would’ve handled his ‘internal opponents’ better had his athletic training staff treated the person rather than physical injuries.

He suggests that coaches and or trainers should demonstrate vulnerability first, creating an atmosphere of acceptance and trust for victims of mental illness. If athletes feel the people that they’re confiding to can relate, empathize, or at least listen receptively to their experience, they will more eagerly reach out for support. A more “emotionally safe” environment allows for athletes to feel more comfortable asking for clarification on the process of mental health treatment, as well as actually partaking in it (Brown).

Most athletes worry about their playing time, scholarship status, and future in their sport, and because their coaches have dominant control over these components, students prefer their coaches were kept in the dark about their mental health disorder symptoms.

The Ball State University survey asked its selected students to rank athletic, academic, behavioral/mental, and advisory services from least comfortable to utilize to most comfortable. Unsurprisingly, the results concluded that athletes were most likely to seek out athletic or academic help, and least likely to employ mental health resources (advisory services like academic advising and career development fell in the middle) (Moore).

Students operate under the assumption that their coaches support their acquisition of auxiliary help in the ‘student’ and ‘athlete’ fields of their role at the university, but not their effort to improve the most ‘human’ part of their identity. It’s more generally acceptable and more commonly practiced for an athlete to publically request help academically and physically, so students aren’t ashamed of the lack of discretion with these amenities and therefore make use of them more frequently.

If the exercising of mental health resources and treatment became more normalized, athletes could partake in them with less fear of the consequences towards their opportunities within their respective sports. Coaches must also introduce and respect a mandate preventing discrimination against athletes suffering from mental disorders during consideration for playing time or status on any given team.

Many objectors deny not only that mental health has an effect on the well-being of athletes, but also the reality that treatment options for these individuals are not conducive to their needs as athletes. The skepticism towards mental illness arises from ignorance and misunderstanding.

Often people write-off symptoms or disorders as mental weakness, a plea for attention, or even laziness. Traditional sports culture fosters the attitude of these excuses by teaching competitors to completely suppress feelings of depression or anxiety while simultaneously preaching an atmosphere of insufficiency where athletes must always strive to improve, where they are “never good enough."

While on a basic level these ideas could serve as motivation or a ‘wake-up-call’ to a disheartened or lethargic player, these concepts should not apply to serious mental concerns because certain difficulties with emotion or behavior could become dangerous for an individual’s health. Society generally handles physical qualms more sincerely and comprehensively than cognitive problems because of how those injuries possess more constitutionality as an ailment because of their visible quality.

However, many mental disorders have physical symptoms in addition to mental ones (like exhaustion, insomnia, loss or swelling of appetite, weight fluctuation, etc.) and they have the same, if not more, of an impact on the athlete’s performance.

While one could argue that almost all universities have some sort of counseling services available to all students (including varsity sport members), they would fail to recognize the lack of standardization of these resources for athletic training programs across the NCAA programs and the disgrace that athletes fear will inevitably come from their coaches and peers should they use these amenities.

Seventy-two percent of NCAA program's only counseling option for athletes is the regular student counseling center, and almost half of the athletic trainers who responded to the Sudano and Miles study believed better care would be provided to student-athletes if mental health services occurred onsite in the athletic training room (Sudano, Miles).

The simple recognition of the widespread existence of mental disorders amongst collegiate athletes cannot save or assuage these victims from their suffering. Not only does the presence and availability of the treatment and therapy essential to these students’ rehabilitation and recovery need to improve, but also the stereotypical atmosphere within sports culture, so that athletes can experience less hesitancy towards seeking out help for their psychological ailments.

The NCAA needs to institute a standardized approach to mental health care and ensure that all the schools within their jurisdiction promote the acceptance of those afflicted by mental disorders. The NCAA regulated method of care should parallel the comprehensive and extensive structure and attention that physical care receives in order to stress the validity of mental health as a significant and real issue.

The stereotypical ‘mental toughness’ that coaches condition their athletes to maintain, the prominent negative perception of mental illness in general, and the fear of a lack of confidentiality and privacy which deter athletes from seeking help can be overcome, but schools must implement change immediately.

Brown, G. Mind, body, and sport: understanding and supporting student-athlete mental wellness. October 2014. https://www.naspa.org/images/uploads/events/Mind_Body_and_Sport.pdf. Accessed February 4, 2016. Google Scholar

[1]Cox, C. (2015). Investigating the prevalence and risk-factors of depression symptoms among NCAA Division I collegiate athletes. Retrieved from Proquest Digital Dissertations. (1592018)

Moore, Matt. “Perceptions of Seeking Behavioral Health Services amongst College Athletes.” Journal of Issues in Intercollegiate Athletics, no. Special, 2017, pp. 130-144. College Sport Research Institute., csri-jiia.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/JIIA_2017_SI_08.pdf.

Sudano, Laura E, and Christopher M Miles. “Mental Health Services in NCAA Division I Athletics: A Survey of Head ATCS.” The American Orthopedic Society for Sports Medicine, vol. 9, no. 3, 1 May 2017. Sage Journals, DOI: 10.1177/19431738116679127