Two years ago Netflix made all nine Hellraiser films available for streaming. I watched them all on a week-long binge.

I really couldn’t articulate why I did this. I’d never had any interest in the franchise, and I knew going in that the vast majority of the movies weren’t worth the bandwidth they used to stream it to me. But I continued on. And I watched one after another with a mixture of interest, ridicule, frustration, and confusion. When it was over with and I had watched the final movie—the generically named Hellraiser: Revelations—I wasn’t sure what I had accomplished.

The summer after, I did it again. And this summer I’ve started again, making my way so far through the first three movies so far.

Tim O’Neil recently wrote an article in The A.V. Club titled “The Lonesome Death of Pop Culture Icon Pinhead” as a retrospective of the Hellraiser franchise’s most notable artifact/analysis of Clive Barker’s elegy to the Pinhead character in his new book, The Scarlet Gospels. I’ve never read any Clive Barker, not his novella The Hellbound Heart (which served as the source material for the first movie), and not his newest work. As a kid, I read Stephen King and John Ajvide Lindqvist and endless creepypastas on the internet instead. I might have liked Barker’s works, but he never entered my orbit for whatever reasons. My connection to Barker consists solely of the Hellraiser franchise, something that I’m sure Barker would regard with mixed feelings, at best.

In O’Neil’s article, he talks intelligently about the faults of the series and the position Barker has been put in by the character of his most famous work turning into something he very much can’t control. O’Neil quotes Barker saying that “the moment you make a story or create an image that finds favor with an audience, you’ve effectively lost it.”

Clive Barker

And that tends to show in the Hellraiser movies. Barker was allowed to write and direct the first Hellraiser movie, allegedly by signing over the rights to the franchise for all sequels and further adaptations, and it shows. While not a perfect movie by any means, the first Hellraiser accomplishes what it does by being consistent within the confines of its 93-minute run. The movie is what it is throughout, with no peaks and troughs of quality. It also makes sense. Man seeks otherworldly pleasures, is rewarded with otherworldly torture. His relation to his brother's wife and the lecherous way he pursues his niece all create a cohesive story that does what it sets out to do, with absolutely no hint of building a larger world for sequels to build off of and exploit.But by creating this movie, Barker set his creation free to the world, and it hit a nerve. The movie was a modest success, critically and commercially, at least enough for the studio to begin filming a sequel they released the following year. Barker lost control of his work, and it quickly became its own thing.

And it shows. There’s no internal consistency to the logic of these sequels. I mean none whatsoever. The first movie emphasizes that the Cenobites and Pinhead will come after you if you open up the Lament Configuration (all of these specific names and details are added in subsequent movies, the original Hellraiser doesn’t name any of its satanic antagonists, nor does it illuminate the specifics of the puzzle box other than leaving it as that, a puzzle box) to torture you with a mixture of pleasure and pain. You open the box because you’re curious about its pleasures, and you become the property of the experiences therein. O’Neil sums up what works about the first Hellraiser, “it was a film about sexual politics in the era of the AIDS epidemic…The message isn’t abstinence; it’s safe sex. If you can’t control your desire, you run the risk of being destroyed, or worse, turned into a terrible monster. The Cenobites’ BDSM costumes are…a reminder of the importance of safety and consent.”

This message of sexual politics is well and good enough, the problem is that these are immediately thrown out in the sequels (which Barker became only more tangentially involved in until Hellraiser V: Inferno, at which point he stopped caring altogether). Hellraiser II: Hellbound brings most of the characters from the first movie back, but to no greater effect. Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth seems more interested in exploring the background of Pinhead by turning him into a posh English veteran more emasculated than menacing, and Hellraiser IV: Bloodlines is notable only for showing an aimless Adam Scott wandering around an Alan Smithee production wondering when he’ll get to be in a real movie and for blowing up Pinhead on a space station (no, really). It’s not surprise that this was also the last theatrical release for the series before it was cast into the dark and indifferent world of direct-to-video.

Adam Scott in Hellraiser IV: Bloodlines

The point is, these movies showcase something understandable to any franchise that goes on long past the original point of arrival on its train of thought, be it your Hellraisers or Terminators or Pirates of the Caribbean. Watching these movies in quick succession and being a lifelong fan of horror in any medium or style, it’s illuminating to see horrible executions of a genre I love. I know these movies are bad, I’m aware. But there’s still an allure to most of them that’s probably in the same genus of emotion that people feel when they listen in on their neighbors’ domestic arguments or read about historical calamities like the Reign of Terror: you’re watching something with so much potential devour itself, like Saturn eating his children in real time. And it’s not even just that these movies are cool because of Pinhead or hell or any of that. Pinhead may be the face of the series, but that’s only because the rest of these productions are so drained of any kind of charisma that Pinhead wins by default. They're interesting for their potential to explore what it is that makes desire so dangerous. The first four of these movies exist on a grander scale than their subsequent sequels on the basis that they were made as feature films under the guise of continuing a franchise for the studio respect and financial gains that come with that. Even if everyone involved was aware of how shitty these movies were, they still tried to pass them off as credible entertainment. After the fourth movie, when the series stopped becoming major productions and started getting passed around to whatever struggling industry-types needed something to put on their resume (and for cheap) that a different side of the series began to show.

The direct-to-video glut of the Hellraiser franchise began with the aforementioned Inferno, which…honestly? Wasn’t all that bad. It’s a fairly standard story about a detective trying to solve a case in spite of (or maybe because of) his personal life’s deterioration (a theme that shows up again and again, most recently and notably in True Detective) directed by a guy who seems to have grown up a little too enthused by David Lynch’s films without ever really grasping what makes David Lynch David Lynch. The movie is predictable, but there’s enough inspired stuff in its production and oddities that you want to see where it goes, if only to confirm it for yourself. The follow-up, Hellraiser VI: Hellseeker, follows the dude from the Allstate “Mayhem” commercials as the protagonist from the first two movies screws around with him. Neither of these movies are good, but considering what direction the franchise was heading and the fact that there’s just a lower bar for direct-to-video, they aren’t the worst things ever made. If nothing else, they show the trend of the Hellraiser films and point out what was probably the series’ fatal flaw from the start: besides the bare minimum of shoehorning Pinhead into increasingly convoluted situations, Hellraiser doesn’t have a specific formula, nor does it have the audacity to reinvent itself.

These movies tend to believe they exist on the same planes as Friday the 13th or Nightmare on Elm Street, where the central conceit is clear and repeatable, but that just isn’t the case in these movies. Instead, what each successive movie in the Hellraiser franchise tends to do is ape one or two elements from the previous film and make up everything else as it goes, resulting in movies that slowly evolve in meaningless ways without ever getting an opportunity to address their faults. And with this, they’re especially vulnerable to aping whatever broader trends exist in horror at the time—they are very much the products of their times. The haunted-house Gothics of the ‘80s are the most obvious lineage for the original, but the technological puberty of the mid ‘90s colors the third movie, while an insistence on grit and broody, super-serious characters colors Inferno. Even the found-footage obsessions of the late ‘00s and early ‘10s makes its way into Revelations.

But I want to stop for a minute from the armchair analysis and bad waxing of the poetic to emphasize something that needs it: after having watched Hellraiser VII: Deader two times in the last two years, I have absolutely no idea what is going in this movie. I thought that maybe I hadn’t been paying enough attention and the movie somehow slipped by me while writing this, so I went back and re-watched it hours ago to try and jog my memory, but no, that did nothing. The movie is batshit insane, and not in a way that feels intentional. Whereas the other movies in the series all fall in the face of excess cheese, convoluted plotting, or half-assed efforts from cast and crew (and Deader certainly suffers from all of these), there’s a special kind of lunacy baked into this movie that’s both noticeable to anyone watching this movie from the first 5 minutes and is totally undefinable for the next 85. Deader exists as the only film in the franchise to make me feel in some way uncomfortable or scared, and it did this because I couldn’t understand what I was watching. The movie is the equivalent of stumbling around the dark recesses of YouTube until you find some dimly-lit, basement-produced video of a forty year-old man showing a tutorial of how he meticulously takes care of his collection of My Little Pony toys, with more than a hint of sexual frustration throughout. If Red Letter Media’s Mr. Plinkett were a real person and took himself deadly serious as a filmmaker he would probably make Hellraiser VII: Deader.

Then there’s the baffling Hellraiser: Hellworld, which tries to work as both a meta-analysis of the series and Scooby Doo-esque murder mystery, but which succeeds at neither because it completely stops making sense two-thirds of the way in (although it was nice to see Aliens’ Bishop finding work decades after he was last relevant).

By the time Revelations rolls around, it all seems to be an exercise in putting an asthmatic, incontinent dog to sleep (the movie was filmed for contractual obligations to renew the rights of the series). The original Pinhead actor—screen veteran Doug Bradley—opted not to return for the ninth movie, calling it a day after Hellworld. The replacement, whose name I knew at one point but really doesn’t deserve to be recalled, serves the movie about as well as anything else in it—which is to say, not that well. The film does its best to recall whatever made the first movie successful, what with the familial drama, themes of sexual appetites and abuse, and a throwback to the first movie’s idea of impersonating people by stealing their skin, and in this way it’s at least more honest than most of the other sequels, but it doesn’t work. Maybe it was these ostensible nods to the original that led the marketing behind the movie to claim Revelations was from the "Mind of Clive Barker", something Barker himself responded to on his Twitter feed, claiming that the movie wasn't "even from my butthole." The acting is flat, the production is cheap, and the direction is so uninspired Revelations feels like painting-by-numbers. If you’ve seen the other eight movies in the series and are at least cursorily familiar with standard horror tropes and archetypes, you know everything that’s going to happen in this movie within the first fifteen minutes, minus the weird incestual overtones and an oddly-compelling standoff in the end that feels more reminiscent of the old spaghetti westerns than anything else Pinhead & Co. have offered up in the past.

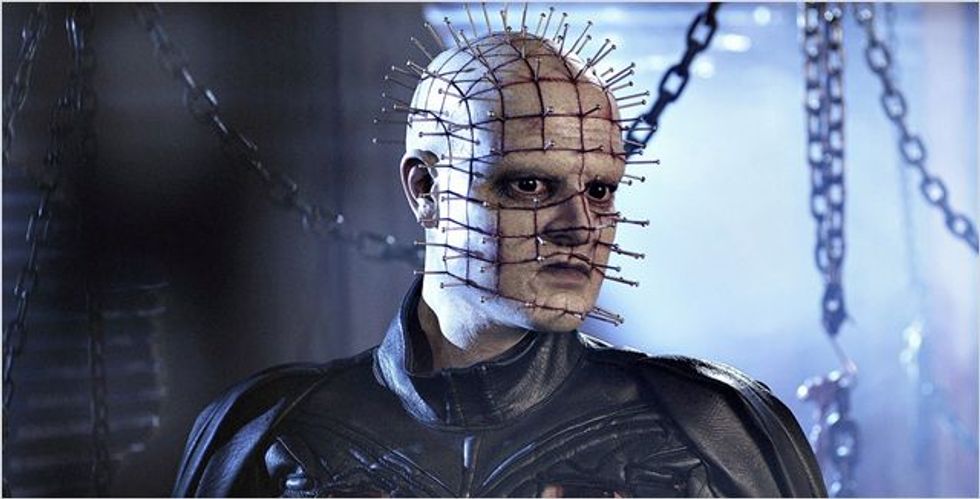

Pinhead in Hellraiser: Revelations, looking more babyfaced than bloodied

And with that, the series has stayed mostly dead, with nothing new being released in the four years since Revelations. Intermittent rumors of a reboot or remake or redoing or whatever pop up now and again, though so far nothing concrete seems to have surface other than an independent take on what a reboot could look like.

And as probably one of like, 14 people who have seen all of the Hellraiser films (and therefore has as much emotional stake in the franchise as anyone could possibly muster), I’m not sure I’d even want a reboot of the series. The Hellraiser movies are an oddity, British horror (at least at the start) going toe-to-toe with American heavyweights in the ‘80s, they never had the cultural impact or financial success of their counterparts, and maybe it’s for this reason that they don’t inspire the same cultural gag-reflex that Texas Chainsaw Massacre reboots or Poltergeist remakes seem to. The saturation that diluted popular horror franchises never seemed to find Hellraiser significant enough to imbue itself into. While, yeah, there are nine of these movies, most flew so under the radar that nobody who values their free time could tell you so. Other movies succumbed to external pressures; Hellraiser was a victim of its own idiosyncrasies. A genuine attempt to revive this series and put it on the big screen again in hopes of turning it into an actual force feels at odds with the aesthetic what we have.

As I watch these movies all the way through for the third time, what makes the most sense about Hellraiser is that it seems to exist independent of any expectations after a certain point. These movies were made for the sake of someone needing something to make, and in that way they showcase a side of the amateurs trying to break into professional filmmaking that’s awkward and bad on an objective level, but endearing on its own terms. Barker may have tried to kill off the Pinhead character in his newest book, but like he admitted, it hasn’t been his baby for a long time, the series and its most important character have lived out a long and semi-natural life cycle, and for all of that, I’m at least thankful I have my own tradition to play into.

I just double-checked, and yeah, all the films are still available on Netflix.

sunrise

StableDiffusion

sunrise

StableDiffusion

bonfire friends

StableDiffusion

bonfire friends

StableDiffusion

sadness

StableDiffusion

sadness

StableDiffusion

purple skies

StableDiffusion

purple skies

StableDiffusion

true love

StableDiffusion

true love

StableDiffusion

My Cheerleader

StableDiffusion

My Cheerleader

StableDiffusion

womans transformation to happiness and love

StableDiffusion

womans transformation to happiness and love

StableDiffusion

future life together of adventures

StableDiffusion

future life together of adventures

StableDiffusion