“Where were you when…?”

For my mother’s generation, the question could be: “Where were you when Kennedy was assassinated?” or “Where were you when the Berlin Wall was torn down?” For my generation, I imagine we might be asked things like: “Where were you when the Arab Spring began?” or “Where were you when Barack Obama was elected president?” But the one question that is definitive for all Americans alive at the time is: “Where were you when 9/11 happened?”

For Oskar Schell, the answer is that he was standing in the living room of his New York City apartment, with the TV on, listening to the telephone ringing.

That’s the simple answer. The truth is far more complicated, and in Stephen Daldry’s (“Billy Elliot”) adaptation of Jonathan Safran Foer’s novel, the truth reveals itself in the story of a young boy struggling to preserve his father’s memories.

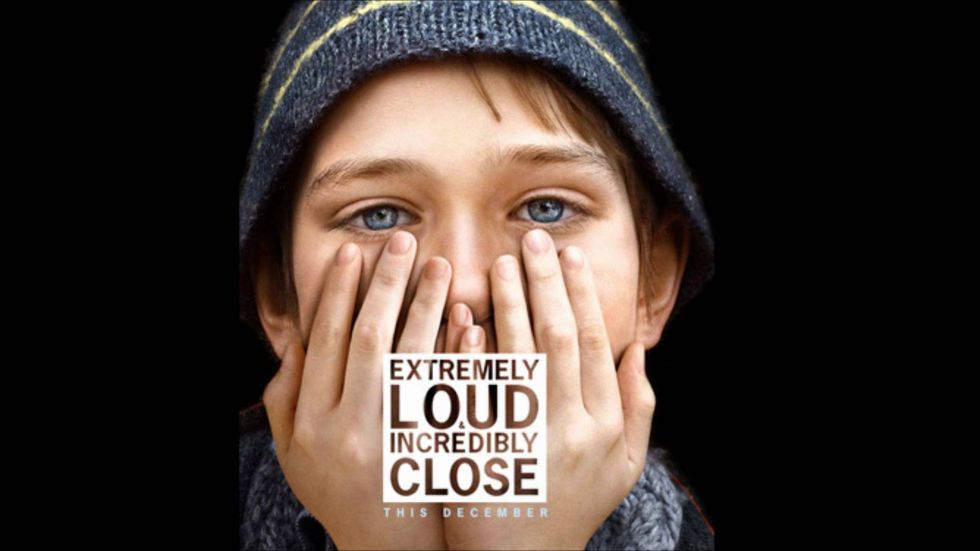

“Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close” (2011) is about a family following the tragic aftermath of 9/11. Nine-year-old Oskar Schell (Thomas Horn), a boy with high-functioning Asperger’s, loses his father (Tom Hanks: “Forrest Gump”) in the attacks, causing a major rift between Oskar and his mother (Sandra Bullock: “Gravity”) that has not healed a year later. The idea of death is something that causes existential crises in the most brilliant of minds; the shock of mass murder even more so. But especially for Oskar, whose life is dictated by statistical information and compartmentalization, 9/11 brings chaos to an otherwise calculated universe. The only way for him to make sense of it all is to find meaning in his father’s death, which he attempts through journeying around New York City in hopes to find the lock that fits a mysterious key his father left behind.

There’s a strange, unsettling line between homage and mockery. Films featuring horrific events sometimes tread this line with as much grace as an elephant on a tightrope. Just go online and read up on some criticism on the relationship between Holocaust and Hollywood or any of the opponents against the Boston Marathon bombing film “Patriots Day”. Do they mean to be insensitive? I certainly hope not. I just think that when one endeavors on an impossible task to accurately describe the point and effects of inhuman events, the resulting production can be decidedly mixed.

And I believe it’s a task that “Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close” just simply was not up to. I applaud its intentions, for it is a film about discovering hope and solace in the face of suffering, but I disprove of its methods.

The movie opens with a silhouette of a man falling in the sky. The image rips apart into ripped, thin panels to reveal a close-up of the young Oskar Schell. The camera slowly pans out. Oskar stares at the audience. His voice whispers over the image: “There are more people alive now then have died in all of human history. But the number of dead people is increasing.”

It’s an eerie, unsettling moment. It’s also pointless and condescending. Not only is the first part incorrect, but the second half of the quote puts so much emphasis on an obvious statement that it feels as though Oskar is saying it just to make himself seem more important than the audience. And this level of pretentiousness never yields; if anything, it increases to where I didn’t know if the point of the movie was to give a heartfelt homage to the 9/11 survivors or for the filmmakers to showboat how clever they can be with airy, philosophical dialogue and contrived plotting.

Do I sound like I’m being a little bit harsh? Yes, and the reason is that I wanted to like this film. I wanted to watch a movie approach the 9/11 victims with the respect and dignity they deserve; instead I felt that the filmmakers treated every single moment of this film as an opportunity to manipulate audience emotions and guilt their way into Oscar nominations (it’s one of the worst reviewed movies on Rotten Tomatoes to be nominated for Best Picture).

The major problem is the direction they take with Oskar’s character. The kid is a brat to everyone (derogatory insults, rude and abrasive commands) he meets. I understand that it’s important to keep an open mind about Oskar’s tremendous grief and his Asperger’s, but the issue is that the film depicts him as a high-functioning, highly intelligent kid and someone who is aware of when he is being offensive to others. So I found a deep disconnect between when Oskar is being impertinent because he’s upset/grieving or when he’s being uncivil for the sake of being uncivil.

And that’s where the film’s preeminence to be clever works against it. If Oskar doesn’t have the tendencies to want to outsmart adults or make pretentious voiceover narration, then the argument can be made that his attitude is chalked up to him simply being a kid. However, the film, in its dramatization, expect the audience to hold Oskar to a higher standard than other children, but when done so, the character rings hollow and seems disengaged from the emotional resonance it wants to project.

As a concept, “Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close” begins from a place of genuine emotion, but in production, the heartfelt messages were overthought and manipulated to the degree that the audience feels more guilt than empathy.

Rating: D+ | 1½ stars