These post-election days witness the Earlham community simmering with emotions. Anger, fear, doubt, and devastation. This atmosphere reminds me of what happened after the Paris massacre last year. Many people called November 13, 2015 "France's September 11." Now, some re-evoke the label to lament Trump's victory. When the epitomes of peace, democracy and equality are under attack from both outside and inside, it's hard not to panic.

What surprises me most about these events, however, is how surprised we were. By "we," I mean those who unwaveringly (and naively) believed in the impossibility of the rise of Trump, who overtly denies the American ideals that we hold sacred. This illusion was corroborated by myriad pre-election polls, which overwhelmingly leaned towards Clinton's presidency. It turned out that there are more Trump supporters than we assumed, and we never understand them enough.

Earlier this year, we were similarly surprised by another triumph of majority rule in its purest (and most extreme) form: Brexit. Unpredictable, of course, but not necessarily so if you spent time wandering around London streets and really talking to people like my Economics professor. "What differentiated them from us," he said, "was that we could see hope in the future, while they could only see despair." This reminds me of a similar conversation with my Chinese professor in the aftermath of the Paris attack last year, as we discussed the history of terrorism, and how it emerged from the fear of being left behind in a world ceaselessly progressing ahead.

I believe that many Americans have the reason to believe that they were deserted. Most major news agencies, indeed, categorically associated support for Trump with racism, sexism, xenophobia, etc. Like Brexit supporters, Trump voters rarely had their stories told with the respect and sympathy they deserved. At least until now, when Washington Post, for example, began asking the silent majority why they chose Trump. We thus read "confessions" of immigrants, Muslims, women, among others, wondering why we never really heard their voices before.

No, we didn't completely mute them. Yet, we simplified their stories substantially to fit our narratives about ignorant, conservative and fearful "others", who were clearly on the wrong side of history. So self-absorbed we were in our media success that we almost forgot them and found ourselves dumbfounded when they finally rose up.

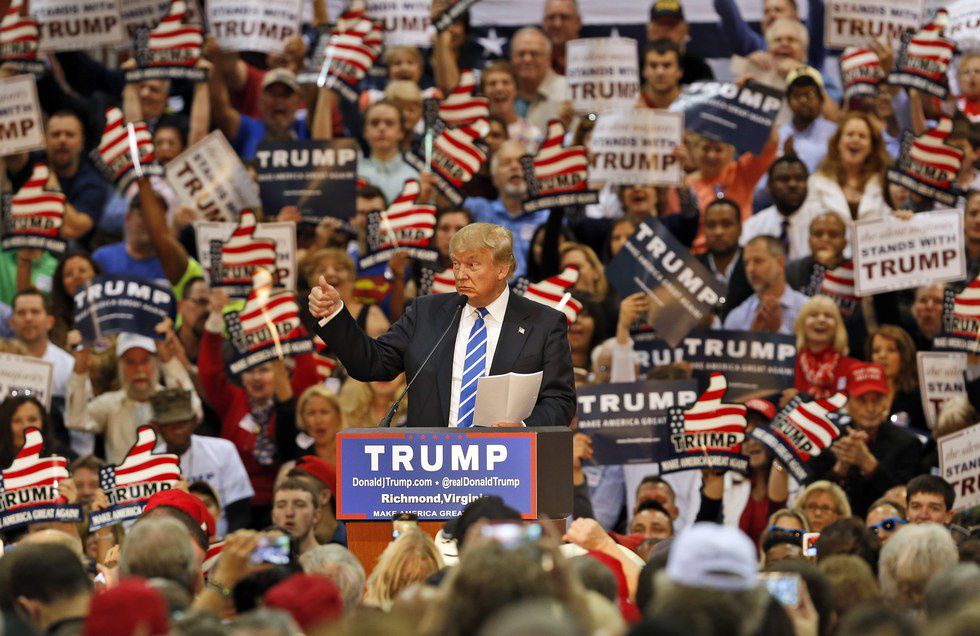

As the veil is gradually lowered, we realize that they are not just the aggressive crowds rallying sexist and racist slogans at Trump's campaigns. Neither are they merely ignorant rednecks who sacrifice common interests for their selfish benefits. Like us, they can see both sides of the coin and can also visualize negative impact from Trump's reign. However, unlike us, they don't have the comfort of sharing personal stories that backup their reasoning. Even labeling their narratives "confessions" indicates a sense of oppression. Sure, it is undoubtedly wrong to make other groups feel uncomfortable by physical or verbal attacks like Trump did. However, if there is a great number of people who can't freely express their personal experience, it's because we choose to categorically judge them merely by their choice.

As I ponder about these unknown "others", I realize that I don't know any Trump supporters personally. Earlham College is a blue dot in the red sea of Indiana, which means that only a few steps outside campus can bring me to explore multifarious stories of Trump voters. Yet I never did so. It's ironic that we college students are willing to cross the ocean for an off-campus semester with people from other cultures, but can't care enough about those in our proximity. It's hilarious that we bring international students together to promote cultural diversity, but can't bear to talk with those who don't share our vision, as if such people have no share in the "better world" we are visualizing.

Speaking about self-righteousness itself sounds self-righteous, as if merely acknowledging differences and vowing to open our hearts can immediately solve the problem. After all, it is unfair to assume that liberals are all self-absorbed and arrogant beings who only shout out big yet blank slogans and treat others as less than humans. We can still love people without accepting their political identity. Indeed, as I asked people whether there was any Trump supporter whose decision they could understand, most said no. There are close relatives and friends whose political affinity they cannot accept, however well they know such people.

This reminds me of a study in social psychology, which points out that close relationship with an individual from the prejudiced group can actually seduce one into wrongly assuming that he is completely unbiased towards that group. I still remember how embarrassed I was when realizing that I still harbored many misconceptions about athlete students, though one of my best friends is in the Cross-country team. Much as I appreciate her, her passion for running is something I know but can never fully empathize and in fact never tried to understand.

This elicits two implications in reflecting the election. First, crucial as political identity is to a person, it is not everything. Hence, it is a mistake to ignore myriad individual differences and visualize all Trump supporters as little Trumps who are equally racist, sexist and xenophobic. What's most dangerous about Trump's rhetoric is essentially its dichotomous nature. He speaks as if the world has only two types of people: those who want to make America great again and those who do not. By absolutely dismissing Trump supporters as abhorrent rednecks, we, unfortunately, fall into Trump's trap by estranging a large portion of the population, who do not necessarily go against the ideals we believe in.

The second, more internalized implication is how hard it is to genuinely empathize with "others". I first realized this when sitting in the post-election forum at Earlham, hearing my friends share their stories and seeing them cry. Though I am an international and female student who will possibly be disadvantaged by Trump's presidency, I don't have parents who confront the risk of being expelled. Neither will I face the immediate threats of increasing discrimination, as I can still spend another two years at Earlham — the little yet safe blue dot. I can offer them, my friends, sympathetic ears and hugs, but how can I genuinely connect to the pains I have never experienced?

You may wonder why I am so preoccupied with emotion, which should not have anything to do with political judgment. Indeed, Brexit and Trump presidency did raise some concern about the majority rule and the excessive role of emotions in voters' decision. My answer is: empathy is the key to establishing mutual respect and trust, which is the absolute requirement of politics. Given the inevitable co-existence of different groups and opinions, politics is the most viable method of reconciling distinct interests without resorting to dictatorship or violence. It is an engagement in endless debates which finally bring all sides involved to a compromise and joint efforts for the common good. The democratic debate involves two sides who have such well-established reasons that their exchange of ideas will help themselves and spectators explore the complexity of the original issue.

In these democratic debates, though only one person may win, his vision and the plan will change a great deal during the debating and executing process. A common problem in teamwork, therefore, is associating the idea with the person too strongly, to the extent that the denial of the idea is the dismissal of the whole person. The only way to prevent this from happening, as I mentioned, is maintaining mutual respect among different groups. However, we are now at a stage when political conversations have become a lost art. At presidential debates, personal attacks prevail over discussions about policies. Among American people, Clinton's supporters criticize Trump's voters as ignorant red-necks, who, feeling their voices unheard, react by rallying even louder at Trump's campaigns. Trump's dichotomous rhetoric may facilitate disorder, but his rise is essentially a product of the longtime chaos and disillusion in politics.

This disillusion refers not only to the anti-elite mindset but essentially to the loss of empathy among different groups, indicating an increasing division in the American society. Ironically, though both Trump and Clinton are not typical representatives of their parties' ideologies, the antagonism between their supporters is greater than it was in most past elections. This political division can be explained by Jonathan Haidt's in The Righteous Mind: "The reason is not that some are good and others are evil. Indeed, the explanation is that our minds were designed for groupish righteousness. This makes it difficult — but not impossible — to connect with those who live in other matrices."

However, most of us underestimate how difficult it is to truly empathize with others. Such an attempt is a book named Strangers in Their Own Land by the sociologist Arlie Hochschild. This project began when Hochschild tried to get to know why people who would benefit most from “liberal” government intervention actually abhorred the idea. She realized she knew no one in the Tea Party and decided to spend five years in Lousiana genuinely exploring their multifarious stories without imposing her judgment. Her experiment proved that a liberal could learn to empathize with Trump supporters and understand their decisions. More importantly, their stories revealed that unlike our generalizations about them, these Tea Party members shared some fundamental values with us, like respect for nature, hope for future's generations. There may be differences in the extent to which we and they value these ideals, but the two groups are certainly not as different as we assume

Surely, there are many elements related to the election and the current division in the American society, including pragmatic factors like economic and political interests. Cultivating empathy is not the panacea for this issue, but it is probably the most viable thing each individual from both sides can do to ameliorate the situation. Since the Paris massacre and then Brexit, the question of empathy has received more attention, yet we may need another lesson to realize how paramount and yet difficult it is to truly appreciate others' stories before judging their political identity. Only by listening without judgment can we rebuild mutual respect, rediscover the art of democratic conversations, and employ politics to heal this divisive society. It will take long, and it won't satisfy any particular groups completely, but it is the only way to progress towards shared ideals without making any groups feel that they are deserted.

As I ponder about this challenge, I feel frustrated when thinking about myriad differences among us that may take tremendous efforts to overcome. There are so many people whose values seem so different from me that it is impossible to empathize with all of them, now that I realize how hard it is to truly empathize. However, as my friend says, we can only do our best given what we have in our immediate community and leave the rest to God, I can join my Earlham friends in efforts to heal each other without categorically resenting Trump voters. I will still protest actions of racism, sexism and xenophobia, but I will also object to categorically labeling groups of people as racist, sexist or xenophobic merely because of their political or religious identities. I will still speak up for what I believe, with the hope of impacting others, but I respect their right to make the final decision based on their particular experience and ideals, which they value as much as I value mine. I will actively check my privilege of origin, which may prevent me from understanding the sufferings of disadvantaged groups, but I will also check my privilege of education, which may seduce me into belittling people whose past experience didn't prepare them for the issues I'm now conscious of.

As I think about my college - the little blue dot - I see blue not as the symbol of a particular party but as the color of thriving love and peace. During the WWII, this school was the refuge of Japanese-American students who faced the danger of being confined in the government's internment camps. In the aftermath of the September 11 incident, the dean refused to hand the information of international students to the FBI. Even after the Paris massacre last year, we stayed strong, prayed, sang, hugged and healed each other without giving in to fear and hatred. Even now after the election, in the midst of all the sadness, fear and disappointment on campus, my professor still came into the class and congratulated Trump's supporters on their victory while upholding the basic ideals of the American democracy. Meanwhile, everyone on campus still hugs, listens, sings and tries every way possible to give each other encouragement and sympathy. In this little blue dot, love prevails over fear and resentment, to the extent that people whose different political identity from the majority of voters of the college should not feel estranged.

Behind this attitude is an unwavering belief in the college's values of love and peace and the nation's legacy of democracy. This democracy, which thrives in the foundation of mutual trust, civil debates and joint actions, will not be demolished by a single person's extreme actions and dichotomous rhetoric. A historic moment like this gives us the courage to step back, reevaluate ourselves and reconnect to our values, so that we can build upon them with reinforced faith and love.