They say a person is most likely to die between the ages of 18 and 25. If you make it past that, statistically, you’re pretty safe till your 60s — unless of course you’re one of those artsy geniuses, in that case watch your back at 27, and don’t carry around white lighters whatever you do.

Since I’ve been climbing the treacherous eight-pronged ladder into early adulthood, I have both experienced and watched my peers experience the aftermath of life’s single inevitability. Whatever your thought’s on the afterlife, I think it’s fair to say that those who suffer most from death are the people left behind rather than the dearly departed themselves. The one universal truth about grief is that no two people feel or understand it in the same way. As a preface to the rest of this article, I want to emphasize my recognition of that fact, and express unconditional support to those grieving in whatever way works for them. But this is an opinion piece, so here it goes.

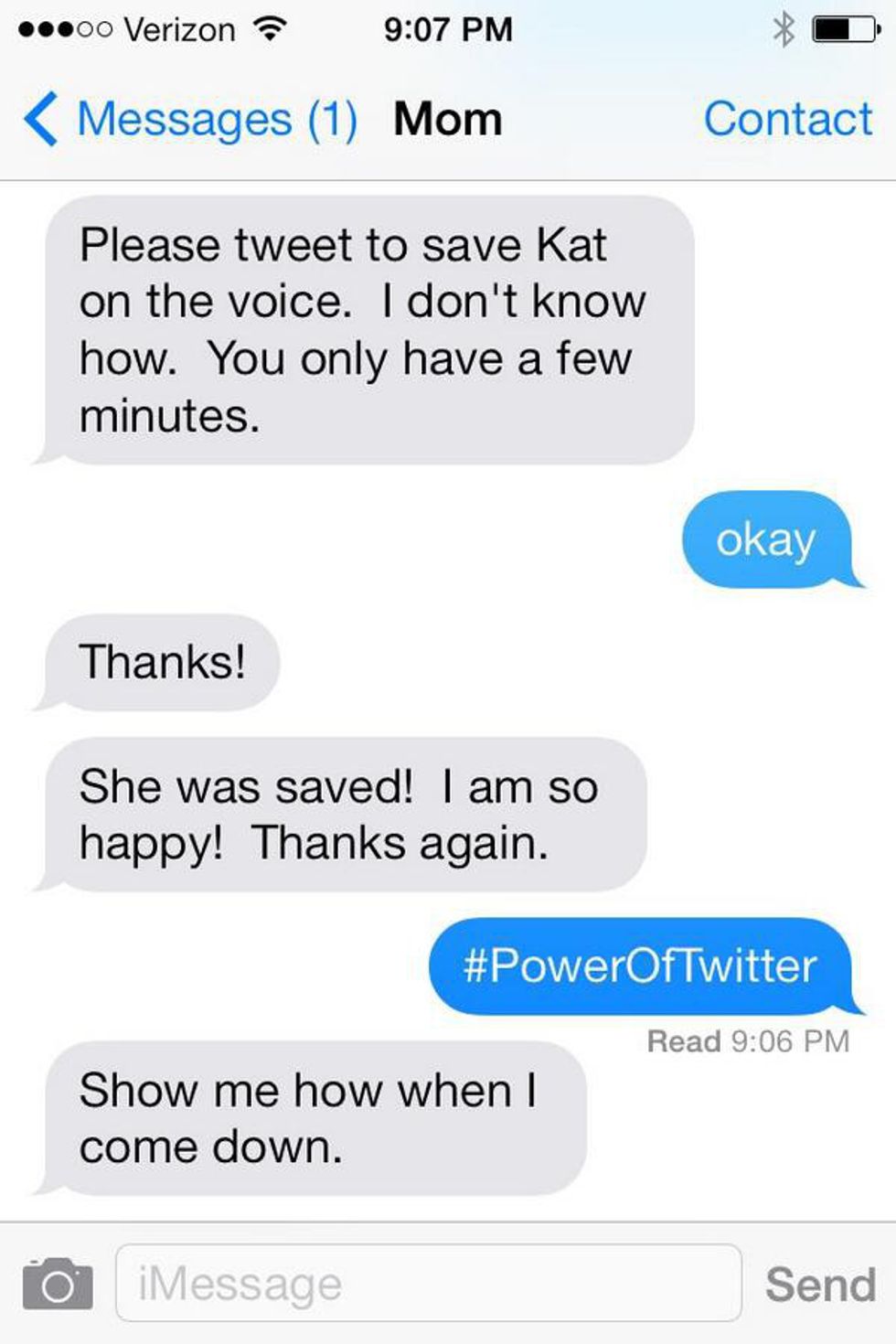

The other fun statistic on 18 to 25 year-olds is that we have a huge presence on social media, I mean we should, we were there when it was born. Try not to cringe as you recall your MySpace page, and think back to the day you transitioned to Facebook. As I’ve watched Facebook grow and develop like a younger sibling that while exciting and wonderful at first, is getting progressively more irritating as the novelty wears off — I have witnessed the rise of the online phenomena of ‘Facebook grieving’. As a part of the generation who pioneered sharing their lives online, I have always been deeply unsettled by what this movement has done to death. We have all seen the slew of wall post’s and statuses, “rest in paradise”, “you will be missed”. These phrases, while they come from the right place have begun to sound more like Hallmark cards than actual feelings.

Thanks to us, people from most age demographics are now participating in the social media community, as a result when someone dies, Facebook feeds damn near blow up with condolences. So in response, I am here with a friendly PSA: think before you post. Please.For those of us who have lost, or just for your average decent human being, the emotional reflex to news of a death is to be empathetic to the departed’s loved ones– to want to reach out and share in the human experience. These kind urges are good and I would never advocate against them, but I would like to suggest that we reconsider what is quickly becoming a norm in how the modern person deals with loss.

It is often argued that social media cheapens human interaction. While normally I believe this is a melodramatic and annoyingly one-sided argument. I lean towards that thinking when it comes to ‘grieving’ on a social media platform. These public online displays are not always wanted. They can actually be incredibly insensitive and hurtful to those closest with the deceased. Allow me to elaborate. People say you cannot compare levels of grief. I disagree. I would never claim to grieve the same amount for an old schoolmate as I did/do for my father, or as I would for my closest friend were she to die.The people who are hit the hardest, are those who shared their entire lives with someone who is now gone. Who knew them inside-out, around, and backward. Generally, this group consists of a very select few.

Those few must be allowed to grieve in a way that is healthiest and the most comfortable for them as an individual. For some that might include seeking the support of their community, while others may find solace in quiet reflection and internal dialogue. The point is: their process should be their choice. You (speaking generally of course), as someone living outside of that inner circle or even as one of the members of that group, do not have the right to introduce another’s suffering to the public eye. For you, what was an “oh what a terrible shame” moment at the kitchen table, is the most painful and life-shattering event of their reality — one that they will confront every day. In this scenario, how dare you ambivalently post a one-sentence condolence status, directed at no one in particular might I add, thereby simplifying someone else’s deepest emotion into Facebook feed spam?

Now having said that — I am aware some might not react as bitterly or as defensive as what I have described, there is something to be said for what social media can do for outreach. But some will absolutely react negatively — me, I will react that way. Earlier I called death “life’s single inevitability”. I retract that — there are two. The second is, if I feel this way, others will too… and of course, others will not. As an advocate for those of us who are private grievers allow me to list the issues that we will have with indiscriminate Facebook commiserations.

- It will seem insincere for someone who otherwise would not know or frankly care to try and involve themselves in the drama of our pain

- Not all publicity is good publicity (see the rant a paragraph up)

- We will resent feeling obligated to accept and respond graciously to posts that are there for everyone to view.

- We do not want extra daily reminders that the person we love is gone– there are enough that torment us in actual reality without little red notification bubbles.

In an era of progress and consideration, I think it would be insane not to address how we understand and relate to the grieving. Would you think twice before posting, “CONGRATULATIONS ON YOUR RECENT SEX CHANGE!” on an acquaintance’s wall? I bloody well hope so, because that is something that they likely would not appreciate you weighing in on and publicizing (*had they not opened up the platform for you to do so). While you might genuinely want to express your support, perhaps a private message might be more appropriate, or even better, a phone call? If you would take these steps of consideration in this circumstance, why not when dealing with death and the bereaved?

But what kind of person would I be to preach sensitivity, and not offer some possible ways to positively address loss? Though you may not be on the front line of grieving for the recently deceased, everyone whose lives they touched do grieve on varying levels, and sharing the burden in a community can be cathartic once someone is ready to. So rather than a status update, or a wall post — create a private Facebook group where those who wish to express their grief and share healing stories are free to do so. This will ensure that those who do not wish to, will not be bombarded with reminders and feel that their loss is inescapable on a media platform. I would also encourage that we social media junkies take a step back and focus on handling grief more directly and personally than sympathies through a screen. Finally and most importantly, if you are unsure of how to go about expressing your sorrow and empathy for your fellow human, I implore you, say so. “I’m sorry”, is a tired phrase that has lost its meaning in overuse. Coming from a fellow griever, a direct, sincere, non-clichéd expression that you are sad and confused too is likely the most comforting condolence a person can offer.