A close friend of mine recently referenced this Twitter post by shut up, mike @shutupmikeginn: ”We get it poets: things are like other things." An oblivious jab at poetry’s use of metaphor, simile, and relating through comparison in general. I chuckled heartily upon hearing it and then...cried a little in the corner. It’s curt. It’s simple. What’s more, the observation it makes seems (on its face) even to be an apt critique of the art form. The effect is a biting belittlement of poetry.

Poets belabor worlds, toiling to complicate and build. We spend eons, draft after draft, and for what: merely to say that things are like other things? With such a phrase, one’s easily beguiled into thinking less of poets, their poems, & poetry as a whole. It forms an implicit voice, echoing: why even bother, poets? Why labor a metaphor? Why zap massive bouts of energy in a simile or hours into an analogy? Why not just say the sun was big, orange, and rising? Why not say sad, mad, or happy?

Dispassionate, I fell quiet. After a split second repose, I swiftly remembered something, though: my love of poetry! With verve, I responded: “Things are like other things, but, isn’t that so cool?” I proceeded to gush over how there’s something profound in the way we relate through metaphors and similes. In the moment, however, I was less than elegant and hardly prophetic.

Being a both a lover and (on my good days) a practitioner of poetry, I became curious about these mechanisms of comparison; these modes by which we relate: what they are, how do we make them, and why even use them. After mulling these questions over, I decided I’d conduct an investigation. Across an intermittent series of interviews, articles and prompts, I’ll be exploring the workhorses of poetry: metaphor and simile. For our purpose in this week’s article, we’ll be focusing on metaphor.

As defined by "Encyclopedia Britannica," a metaphor is a "Figure of speechthat implies comparison between two unlike entities, as distinguished from simile, an explicit comparison signaled by the words like or as.” So, we‘re comparing two unlike things...but what’s so important about the differences between metaphor and simile? Let’s take a look at this example I’ve written:

Metaphor: My excitement is bright sun welling in a prism of frost.

and

Simile: My excitement is like bright sun welling in a prism of frost.

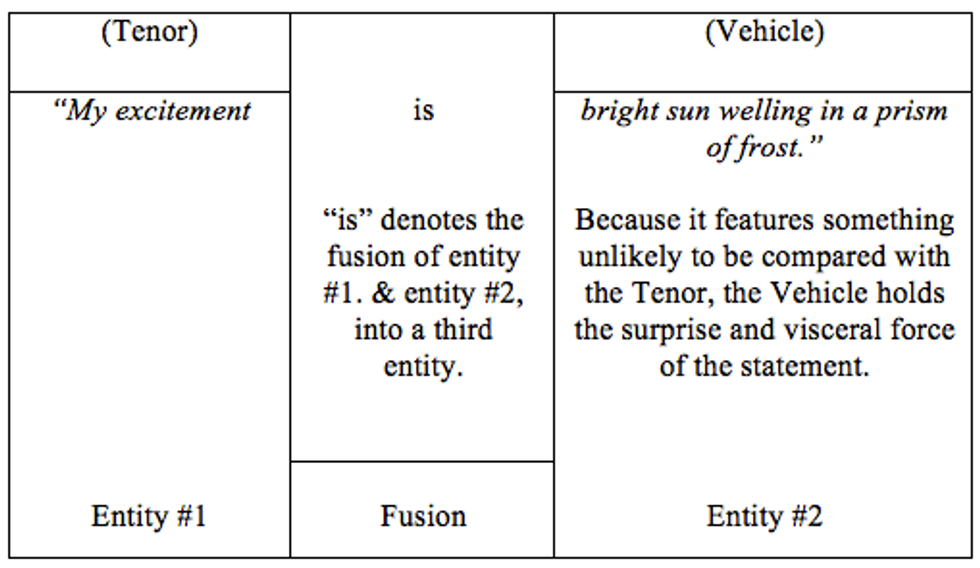

Notice how the metaphor creates a qualitative leap, fusing the speaker’s excitement with the sun’s light (swelled in an ice prism)—Whereas, the simile is merely making a comparison; this is like this, as if to say that while they share similarities, they still remain separate. In a metaphor, the word “is” merges one with the other, avowing or implying that a third entity has formed. This qualitative, entity merging “is” exudes confidence and force, giving metaphors their boldness. But what are the gears and cogs of metaphor; what’s under the hood?

Through my research, I discovered a section in "Literary Terms: A Dictionary" that explores the anatomy of a metaphor, it reads: “In The philosophy of rhetoric (1936) I. A. Richards distinguished the two parts of a metaphor by the terms tenor and vehicle. The tenor is an idea with which another idea (the vehicle) is identified. It is in the vehicle that the force of such a comparison lies. When Macbeth says that life is but a walking shadow, life is the tenor of the metaphor in which walking shadow is the vehicle.”

With this in mind, here’s our example from before: My excitement isbright sun welling in a prism of frost.

In terms of metaphors, the best engage our senses. They imbue the reader with vivid imagery, and sensory information, allowing them a more visceral experience. This brings us to our next discussion point: Why make a metaphor?

Just as with many other figures of speech, Metaphors are a staple in every day conversation: Emily’s an early bird while I’m totally a night owl, or my room’s a disaster during final exams. Metaphors (and similes) create imagery around concepts that might otherwise seem flat. Though, as my research has unearthed, there is somewhat of an expiration to how long we consider a metaphor, a metaphor. “When a metaphor, such as “the arm of the chair” has become so common that it is no longer seen as such, it is called a dead metaphor…” (Literary Terms: A Dictionary, 142).

Generally, I think conversational metaphors create fast moving vehicles (pun intended) for our concepts to travel on, resulting in communicative shortcuts. Saying “I prefer to wake up early” or “I prefer activities in the morning, as opposed to doing things at night” is cumbersome and boring. Whereas “I’m an early bird” travels fast, transporting our meaning, or the concept of being a morning person into an imagistic world where it’s more quickly understood. Image, in this way, is employed to give us and our ideas a universal meeting place. Metaphors don’t just make for great idioms; they also make for great poetry.

Part Two:

Sad, happy, mad, excited—these are as good as closed doors! Reading them doesn’t tell you much about whom, or what they are in reference to. They’re superficial words which evoke little beyond our personal associations or stock definitions. Speaking only to a fraction of the worlds they’re meant to represent, these words leave you guessing at the gate, and, not to mention, they’re just plain boring! But in a Metaphor, new dimensionality is added to an idea/ word/ emotion etc.

I discovered this helpful list of famous metaphors on http://literarydevices.net/a-huge-list-of-short-metaphor-examples/.

“Art washes away from the soul the dust of everyday life.” –Pablo Picasso

“Conscience is a man’s compass.” – Vincent Van Gogh

“Chaos is a friend of mine.” – Bob Dylan

“All religions, arts and sciences are branches of the same tree.” – Albert Einstein

“Dying is a wild night and a new road.” – Emily Dickinson

“Fill your paper with the breathings of your heart.” –William Wordsworth

Notice how the vehicles of each metaphor grant the reader new terms under which to view the tenor. In Vincent Van Gogh’s “conscience is a man’s compass.” conscience comes packaged with a conceptual and imagistic aid. A compass (the vehicle) gives conscience (the tenor) a staircase beyond its stock definition.

Tenor and vehicle are linked by “is”. Innately unlike one another, yet link them through a few obscure attributes and “Bam” - there it is! When this link is strong enough, it persuades us to ascend a stair that extends beyond logic. One can’t literally be friends with chaos. Religion, science, art – these aren’t literal branches anchored to a literal tree. But the mutual characteristics of vehicle and tenor are strangely apt and so we don’t refute the staircase. With our inner critic unarmed, we’re prepared for a communion that partakes of impossibilities. Because metaphors bypass logic, they free themselves from the laws of gravity. They sharpen our imaginations to consider with new and strange specificity.

They’re not just figures of speech, they’re also figures of abstract consideration “Many critics regard the making of metaphors as a system of thought antedating or bypassing logic” (Encyclopedia Britannica.). And with them, poets establish that the rules are no longer tethered to literalism. Takemy example for instance: by fusing excitement with sun glinting off ice (stating that one is the other) I created a new entity - a new, illogical kind excitement. Now this concept has textures that it hadn’t prior.

Here’s one from Emily Dickinson’s 314: “‘Hope is the thing with feathers, that perches in the soul.” Notice how the vehicle spurs the reader’s imagination to grapple with the stranger, more specific essence of hope. A feathered thing that perches in the soul becomes an illuminating staircase, extending beyond what we thought we knew of hope (old flat comes packaged in strange new and language is revitalized). Emily Dickenson could have defined hope the same way as Dictionary.com: “a feeling of expectation and desire for a certain thing to happen” or “a feeling of trust.” But there would have been nothing added to make hope belong to the reader. In the poem, the reader’s imagination must claim the staircase, thinking of one thing through the terms of another; They complete the metaphor. They finish the image that the poet constructed and left for them there. This makes it theirs.

To be continued…

Energetic dance performance under the spotlight.

Energetic dance performance under the spotlight. Taylor Swift in a purple coat, captivating the crowd on stage.

Taylor Swift in a purple coat, captivating the crowd on stage. Taylor Swift shines on stage in a sparkling outfit and boots.

Taylor Swift shines on stage in a sparkling outfit and boots. Taylor Swift and Phoebe Bridgers sharing a joyful duet on stage.

Taylor Swift and Phoebe Bridgers sharing a joyful duet on stage.