I am the social media coordinator for Wheaton’s branch of Odyssey, and I am frustrated with this platform.

Odyssey has a bad reputation in general. Many may be familiar with this widely-circulated article about why Odyssey is a bad website. However, this criticism attacks specific articles and takes them to be indicative of the whole website, a philosophical fallacy. I agree that the highlighted pieces are not good, but it’s important to keep in mind that these articles were published by Odyssey for a reason. When I first started, I found this platform inane but harmless; as I continued as a contributor, I saw that the environment was actively detrimental to the writing process. Rather than generalize based on a few examples, I wish to talk about the overall structure of the Odyssey that allowed these articles to exist, and why it doesn’t work well as either a social media platform or a publisher.

To begin, I’d like to ask a question: why is the site called “Odyssey,” and why is the writer’s interface called “Muse”? These names invoke images of divine inspiration, of daring adventures and relics of an ancient era romanticized by time. Yet nothing about this platform suggests an epic journey forward building toward some ultimate Homeric goal; it just seems like conglomeration of miscellaneous ideas, and this title is misleading and nonindicative of the function of the site, and falsely ascribes allegorical reverence by invoking the name of a classic title.

Odyssey has no central theme that ties it together. Most other major web-publishing outlets have a common theme or something that ties it together. The only thing that all the articles have in common is that they are generally written by people between the ages of 18-35. This in itself is not an inherently bad thing, as it allows total freedom on the subject matter. But this also means that the platform lacks coherence and focus; there is no clear objective. There are some confusingly labeled categories, such as “Ideas” or “Lifestyle” or "Scene," none of which lend a clue in discovering the scope of the work. Odyssey is trying to be a satire site and a news outlet and a fiction publisher and a clickbait Buzzfeed knock-off all at once, and cannot commit to a single direction. By combining all these elements, it’s not easy to separate parody from earnestness or fiction from anecdote at first glance, and the readers get confused.

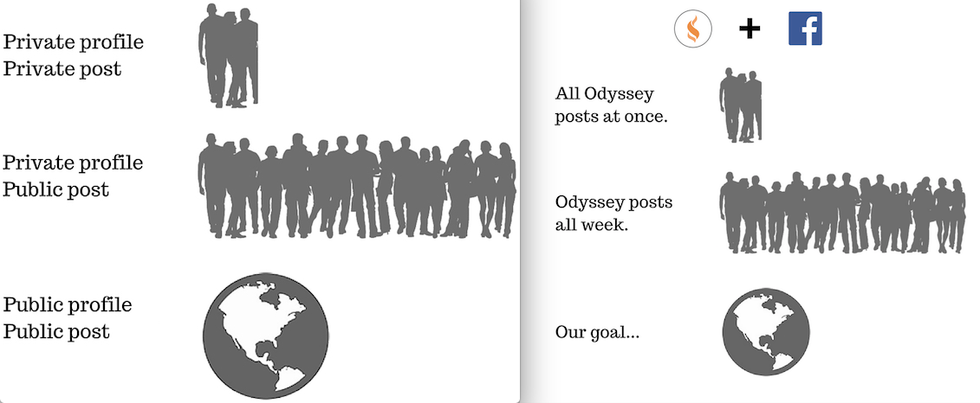

Even the content creators themselves aren’t sure what Odyssey is. This article and this one make it clear that the Odyssey is not a journalistic platform, while this one, from The Odyssey Community itself, encourages journalistic practices in writing. The concept is entirely nebulous with no concrete instantiation, much like this infographic that they keep using in emails with different captions applied:

There’s an underlying lack of consistency even in the naming of the platform; is it Odyssey or THE Odyssey? There is disagreement even among these top two search results:

In an attempt to discover the actual intent of the creation of the Odyssey, I took a look at the “about” page:

This mission statement is not well written, for a start. It reads more like a panicked stress-vomit of buzzwords than a genuine attempt at describing what the platform does, which could be put succinctly as “We publish things written by people.”

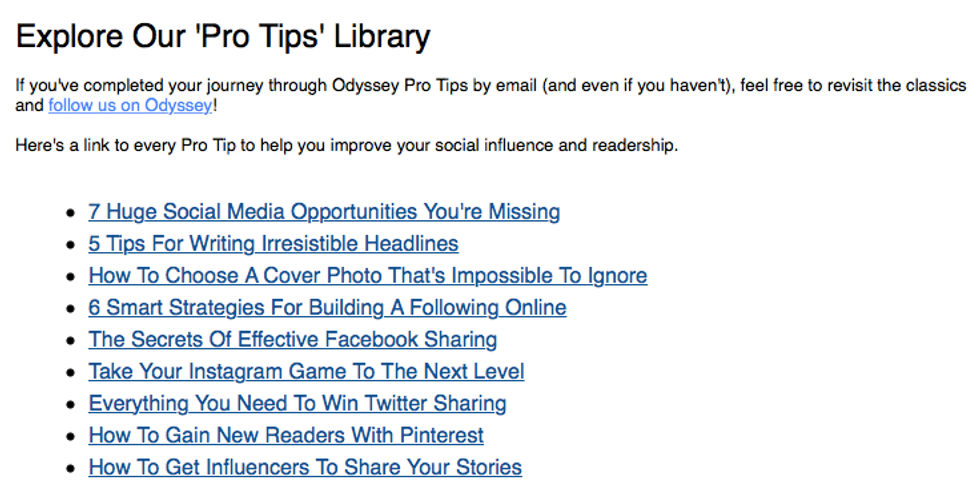

I could talk about the dual use of the verb “democratize,”or the gratuitous use of numerical terms to instill confidence, or the fact that I read this entire thing and still have no idea what this website is. But what I want to focus on is the phrase “organically amplify,” used twice here in reference to the natural dendritic spread of web-based content. Because, to me, nothing about this website is organic. It’s deliberately marketed to attract attention; it’s engineered to be the most efficient clickbait there is. Titles are changed to become more click-worthy. Writers are encouraged to write headlines and subheaders that are deliberately designed to be picked up by Google searches. In the emails sent to contributors, more emphasis is placed on the branding of the content than on the content itself:

All of Odyssey’s “pro tips” are not about how to write good content, they are about how to share the content that you produce. Often articles are not about what the person cares about, but about what will get the most views. Most jobs, in general, reward based on the amount of time spent working toward a goal. I would rather see Odyssey reward consistency or quality rather than sensationalization. Writers should not feel the need to rely solely on pop culture references to get more views.

Odyssey claims to have rebranded itself as a social networking site. And yet, the focus is entirely on sharing content to other sites in hopes of garnering public attention. This offers little support to help aid the writing process, such as lessons on citations, permalinks, leads, or sourcing photos. The business model of Odyssey is solely based on gaining views, not producing good content.

Some would see this as a positive: anyone can have their ideas shared and it has an equal chance of going viral! It sounds almost like a democratic utopia. Nothing gets rejected. Nothing is “not good enough.” Nothing is censored. This kind of acceptance is radical and unapologetic. How could this be bad?

With the promise of an inclusive writer base comes the necessary evil of low-quality writing. There is no form of quality control. Misinformation and poor writing slip past easily; some have typos in the titles that have never been corrected. I support that the young oppressed millennial everyman is getting a voice, but that voice has a responsibility to be factually correct, to be well-written, and to be creative.

Of course, fact-checking is most applicable to news stories, but opinion pieces are not immune. Why do people write opinion pieces? Presumably, they want to portray their position on an issue in a light that either persuades or at least makes justifiable their ideas. Articles that make an argument must be supported by evidence and avoid falling victim to logical fallacy. Odyssey does little to no editing on the material in their articles, so good content is given a bad name by the large quantity of bad articles that slip past. With a simple peer editing process, writers could get multiple challenges to their thinking and articles that fundamentally misunderstand a concept or claim to speak for an entire demographic can be weeded out or improved.

Even if the content is correct and unobjectionable, it often does not add anything new. News articles are usually just summaries of other articles, and most of the gif-laden listicles I’ve read do not provide a new or interesting perspective on a topical issue. Sure, they can be fun to read, but it’s nothing I couldn’t just as easily get from Buzzfeed, which actually pays its freelance contributors. Can one really be proud to say they write for a publication with such low standards for selectivity? I, for one, would not be proud to get into a school, only to realize that 100% of other applicants were let in, plus a few people pulled in off the street to boost numbers. I was given the title of social media coordinator because no one else applied, not because I was qualified for the job.

I think that the large amount of rushed, unoriginal articles can be attributed to the once-a-week deadline, which causes writers to churn out subpar writing on a regular basis. As the social media manager for Wheaton’s branch of Odyssey, I have seen my fair share of articles that were titled something similar to “What It Feels Like To Have Writer’s Block.”

Then again, it’s hard to develop ideas from the community when the process is so individualistic. There is no place for contributors to bounce their thoughts off of others, to get feedback that improves their argument, to receive a fact-check if they need one. The submission process is an echo chamber that only amplifies to creator’s views and doesn’t encourage collaboration. I would love to see a peer review process, in which ideas are questioned and writing is challenged by an outside perspective.

Odyssey, in truth, cannot hold writers to a high standard because the writers do not truly “work” for the company. The company is receiving thousands of pieces of free content per month, and looking into the mouth of this proverbial gift horse would seem inadvisable, as writers may quit once their work is viewed with a more scrutinizing eye. This website is an exercise in glorified volunteerism.

A few months ago, the Wheaton branch was forced to shut down its Facebook page, which significantly limits the potential audience of Wheaton-produced articles. This was done because Odyssey is attempting to become a social network itself. And yet, the success of an article is determined by how often it is shared to other social media platforms like Twitter, Facebook, and Pinterest. Now that college branches have been silenced, Odyssey can promote whatever content it thinks will get an audience through its singular social media presence, and individual communities cannot promote their own content at all. In an attempt to “centralize the brand,” Odyssey ensures that only the content it deems important receives exposure.

One of these articles I was encouraged to post and share on Facebook as the social media coordinator was this one:

As the passive aggressive caption suggests, this article holds no interest to me. The only reason we were asked to share it is because it connects the platform’s brand with a big name. What was deemed important by the company was to appear “legitimate” by getting the opinion of an old cis straight white male on the issues of millennials.

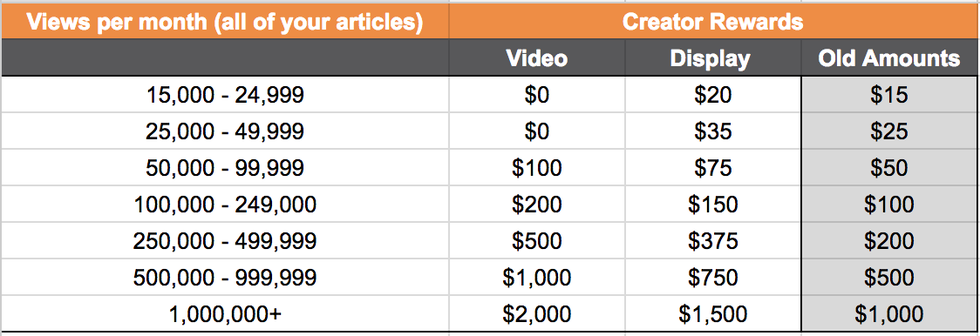

Odyssey is a little bit like the American Dream: it holds up the successes of the few to keep the masses complacent. By showcasing articles which have achieved the status of “viral,” it instills in the hearts of writers that their work may one day be as widely shared as The Dad Bod Article. This is nothing more than an impossible ideal to most contributors; very little of the profits reaped from advertisements ever makes it down to the writers. No matter how often you share an article on Facebook, it still won’t reach an audience. The first incentive reward requires 15,000 page views on a single person’s articles within a month span. Wheaton College only pulls in about 3,000 views per month, total, for all articles published by all authors.

This situation was not much better when the $20 incentive for “most shared article for the community” was in place. The practice fostered competition with fellow writers within a community, which is obviously not the proper environment for ideas to flourish. I also learned that it did not matter where the notifications came from. As I found out through trial and error, you could share your own article on Facebook multiple times under the “only me” option so that the article doesn’t show up to anyone else, and it would still count. If you comment on or “like” your own post, those interactions count as well. While a disingenuous method of getting “shares,” it was still effective to the final numbers that determined whose article was the most engaging. Theoretically, you could be the only one to engage with your own article and it could still win the article of the week incentive. Odyssey only gives credit to raw numbers, not the meaningfulness of the interaction.

Most other media outlets pay you as a writer upon acceptance or upon publication. Odyssey thrives on what is described in another article as free labor. Because Odyssey is so unselective with their material,they cannot afford to pay all those who build up the brand, but only those that they choose to endorse. Because Wheaton no longer has a page set up to distribute our content to our community, it is harder to get the attention or traffic to the people who would theoretically enjoy it the most: our college peers.

There are lots of little things that I don’t like about this website. Lack of paginated result pages; the inherently confusing writer interface; minimalist navigation; infinite scrolling; the color scheme. But what really frustrates me is the business model and the philosophies behind the apparently egalitarian platform.

There is good content on Odyssey. I’ve read articles that were genuinely interesting and made me laugh, but they were few and far between. I don’t come here to attack those who contribute to Odyssey; it is the overall system that I have a problem with. I don’t think I am too good for Odyssey; rather, I wish my writing would be held to a higher standard. I can take my writing to the school newspaper or the literary magazine, where it will be challenged both idea-wise and grammar-wise. Or, if I wish to publish my own opinions and experiences and take accountability for my own writing quality, I can get the same amount of exposure by publishing it to my own blog. I appreciate the intent behind the platform, but it needs to be severely reformed if it actually wants to accomplish its objective of giving millennials a legitimate, respected voice.

I have been an Odyssey contributor for a few months now. I am reluctant to say that I “worked” for the company, for I had never been hired, never received a salary, and honestly did not put a lot of effort into what I did. I was fairly active in my article production, because I had a challenge: to create something that was unpublishable. I continued to write more and more obscure, absurd and a little bit crazy pieces, setting the bar lower and lower for myself, hoping for a day when some editor or another would tell me that my article was not worth publishing. That day never came.

This is my final challenge to Odyssey: You’ve published on the astrological value of cement mixers; will you publish this?