Do you know how much dust a bookshelf can accumulate after sitting, relatively untouched, for approximately ten years.

I do, and the answer is “a lot.”

In related news, I recently went through a shelf full of books from my childhood and early teenage years. Though at first I wasn’t paying much attention to the titles, as I thumbed through old covers memories of worn paper and familiar characters came flooding back to me. This one I bought from a book order in elementary school (and this one, and this one). This one my mom lent to me and never got back. This one I purchased after reading the first half on the floor of a used bookstore.

The more I paid attention, the more I began to notice a trend—so many of my old, beloved stories had female protagonists. These were novels that I read between the ages of about six and fifteen, and I noticed myself picking up book after book that featured a strong, heroic girl or young woman as its main character. From Annie in Mary Pope Osborne’s The Magic Treehouse series, who goes on magical adventures across space and time, to Alanna, who becomes a knight in Tamora Pierce’s Song of the Lioness quartet, my childhood was absolutely flooded by strong female influences gilded on the page.

Unfortunately, my experience with reading is far from universal. My parents encouraged me to find independent, intelligent, and perseverant women in my fiction, characters that I could learn from and relate to as a young girl. This trend was one that I continued as I grew up and began to choose novels for myself. However, a startling study by Florida State University a few years ago found that less than a third of children’s books written between 1900 and 2000— 100 years of literature— featured an adult woman or female animal in a prominent role. By contrast, adult men and male animals were featured in… take a guess… every single book in the study.

I think most of us are on the same page about why the systematic underrepresentation, misrepresentation, or outright erasure of women in media, including but not limited to books, is problematic. Just in case there’s any question, though, let me break it down.

We construct our understanding of the world based upon what we see, hear, and experience, starting during childhood and continuing throughout our lives. Inarguably, the conception of the world that we develop during childhood and adolescence plays a significant role in the way that we approach our circumstances and ourselves well into adulthood. There are countless factors that play a role in cultivating our understanding, and media is no small part of that. In addition to what we gather from our family, friends, and teachers, what we see on billboards, on television screens, and between the pages of books shapes who we become.

So for me to see girls being the heroes of their own stories rather than relegated to the position of damsel in distress? That was huge! It was so important to my own self-perception to see perspectives preaching that girls can and should be smart, hard-working, and independent. I wanted to be as adventurous as Piratica, as strong a leader as Bluestar, and as curious a learner as Laura Ingalls Wilder. Reading about characters like these helped to ingrain what my parents always wanted to teach me: that girls could do and be anything they set their heart to.

But as I said before, my experience is, regrettably, not one that is shared by many young people. Although media attention in recent years has helped to encourage the publication of books by and about women (and other marginalized groups), there is a continued disparity that prevents a lot of children from getting the opportunity to see themselves on the page. In a study that went viral earlier this year, it was found that less than 20 percent of children’s books depicted female characters in a job, compared to 80 percent of male characters. 25 percent did not feature female characters at all.

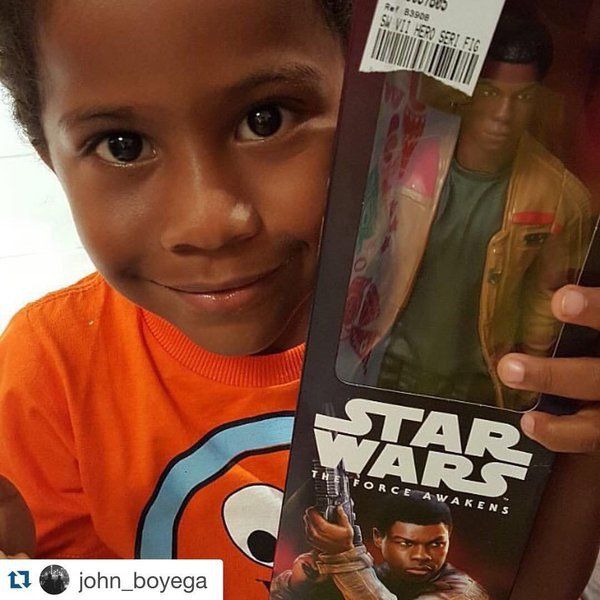

And what about other minority groups? A study last year showed that only about 8 percent of children's books featured Black main characters, and an even smaller percentage spotlighted Latinx, Asian, or Native American protagonists. The experience of people of color, and women of color in particular, is thereby marginalized from childhood in yet another way.

That’s not even accounting for LGBT+ youth, which is still treated as a taboo discussion topic by many. Many continue to cling to the antiquated (and fundamentally homo-/transphobic) belief that understanding or even seeing gender and romantic diversity is somehow damaging to children. This is in spite of the fact that they are inundated with images of heterosexual romance from a very young age— and, more importantly, despite the fact that some children may identify as LGBT+ themselves starting at a very young age.

As a matter of fact, I wasn’t able to find statistics regarding LGBT+ representation in children’s literature at all; the best I could do was a study on YA fiction, which is still very relevant for teen audiences. In 2014, “mainstream publishers published 47 YA books…. a 59 percent increase from 2012.” That sounds really great, until you realize that more than 10,000 YA books are published annually, meaning that LGBT fiction made up a measly .47% of that market, a much less encouraging statistic.

So what can we do? Obviously there is a long-standing and continuing problem with representation in literature for young people across the board. More and more light is being shed on the issue, so what now? First of all, become the audience. If you want to encourage the production of more literature targeted toward marginalized groups, consume that literature. Buy books with female protagonists for your daughters, your nieces, your sisters, AND for your sons and brothers. Support writers of color. Endorse indie publishers specializing in LGBT fiction. Recommend novels featuring diverse casts of characters and affirming messages. Make sure that writers and publishers alike are aware that there is an audience and an economy for these kinds of stories. Hell, if you’re a writer, go tell these kinds of stories yourselves, and make sure that everyone gets to hear your unique and beautiful voice. Help to build fictional worlds that are representative of the remarkable, wonderful diversity present in our real one.

Finally, follow the example of some of our smart, strong, sassy young heroines and make a stand. Don’t let anyone tell you that you can’t be a hero. Don’t let anyone convince you that you are less than. And if anyone tries to stop you from reaching your full, incredible potential, you just tell them where to shove it. You’ve got books to read and dragons to slay.