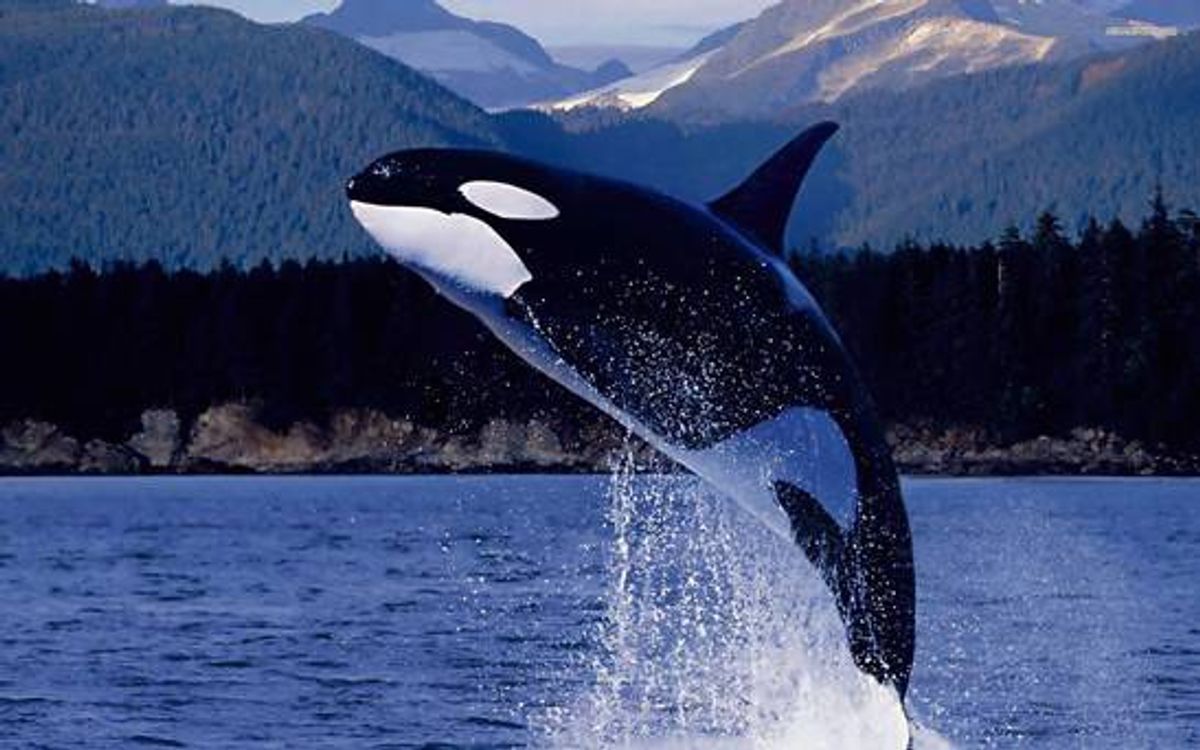

Growing up, I’ve gone to many aquariums and zoos, where I have been awed by the creatures, big and small, who have stared back through glass walls. Many others have also had this experience, including those who have gone to SeaWorld and have seen the live Orca Whale Shows. Some viewers have been amazed by Orca Whales and moved on with their lives. Others have been inspired to work work in conservation or directly with the amazing creatures they saw. Overall, they are good places for learning, research, and entertainment, but what about the well being of the animals existing in the space?

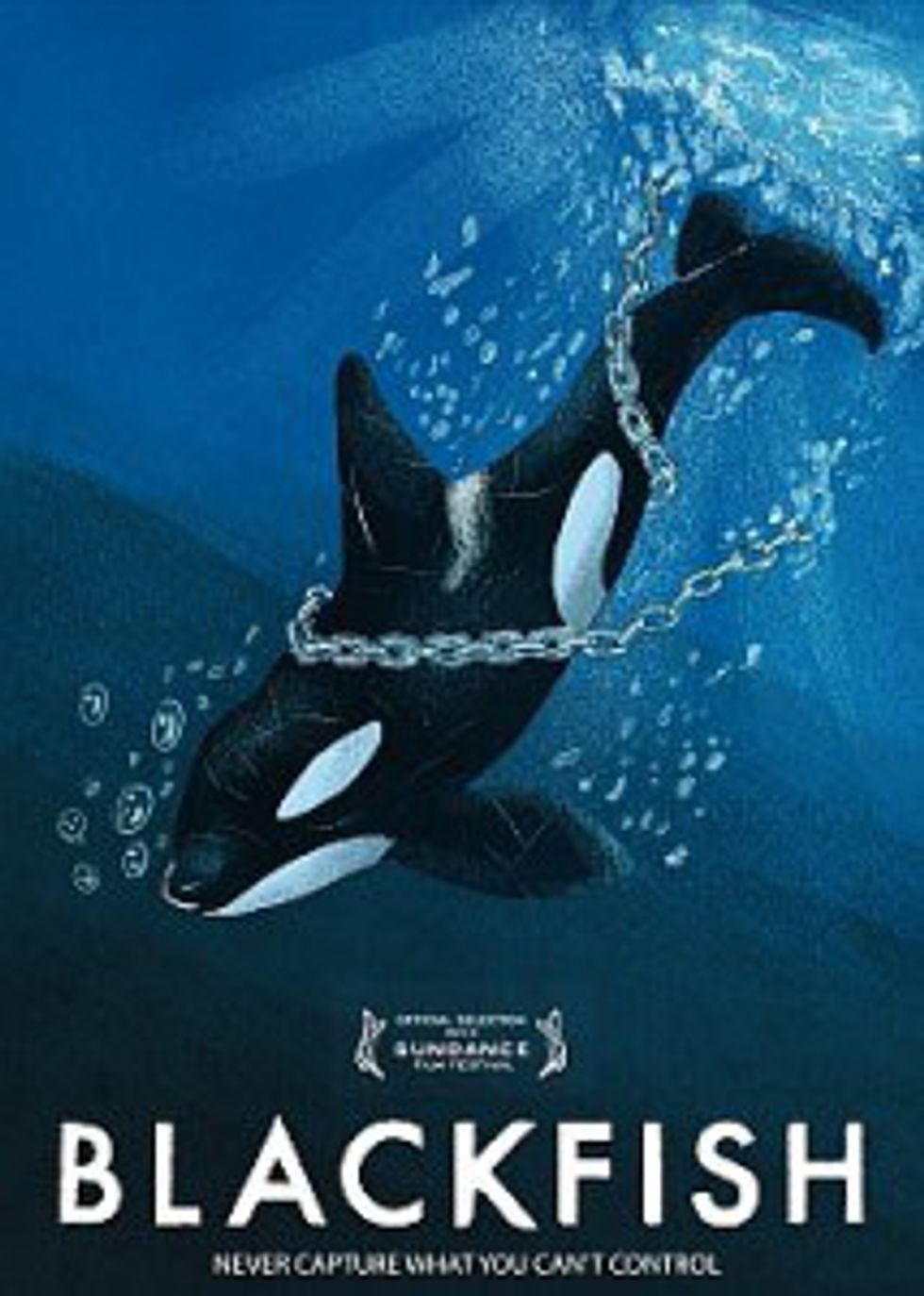

Over the past several years, SeaWorld has made the headlines big time. In 2013, a documentary titled “Blackfish” was released to the public. The documentary follows the story of one of SeaWorld’s male orcas, Tilikum, who was involved in the death and injury of several SeaWorld trainers. The documentary interviews former trainers on their knowledge of incidents involving Tilikum, among other SeaWorld Orcas, as well as several other cases that highlight the impact living in SeaWorld has had on the the whales’ health. Last November, roughly three years after the release of “Blackfish” created a tsunami, SeaWorld announced they were making changes to their Orca show. More recently, on March 17th, the news came out that SeaWorld will be ending their Orca breeding program. So, is that good or bad? Honestly, it's not all black and white.

In the time between the release of “Blackfish” and SeaWorld’s latest announcement, plenty of conversations have focused on SeaWorld and whether animals the size of Orca Whales should be kept in captivity. Many organizations have openly stated their opposition to SeaWorld, including the production crew for Papertowns, who opted to cut the book’s SeaWorld scene from the movie. (Read about it here.) Affecting many viewers on a strong emotional level, “Blackfish” definitely raised questions on the morality of places like zoos and aquariums.

So is it okay to put animals in zoos and other similar situations? Aquariums and zoos are great places for scientists and the public to learn about animals. Due to the negative impact humanity has had on environments around the globe, these places are also a way to save species in danger of extinction due to habitat loss. Observing these animals up close may help conservationists' efforts to save both animals and their habitats. But when animals seem relatively safe from extinction, why not just observe them in the wild? As the mental and physical health of individuals kept in captivity has been examined, we need to re-examine what we are doing. When a species becomes extinct in the wild, captivity is sometimes the better option, but when safety in captivity is a concern, something else needs to be done.

Reintroduction of animals to their natural habitats has been tried several times. In some cases it has worked and populations have been re-established. In other cases, attempts has failed miserably - the individual is too comfortable with humans for its own safety, or it just can’t survive on its own due to injury or lack of survival knowledge. These individuals are taken care of and are usually used to learn about the species and educate the general human population.

Humanity has caused plenty of destruction, both to ourselves and the species around us, due to our global impact. It’s gotten to the point where WE are the cause of the sixth extinction - aka, existing species are dying out faster than new species evolve. So yeah, it’s not YOUR fault specifically, it’s just when you put all of humanity together, we have a HUGE impact on those who co-exist with us.

So if we could actually communicate with animals, what would they tell us?

I think they would tell us to right our wrongs. But what can be done? That’s a question that has been asked for years, and will continue to be asked for a long time. The simple answer is that we need to fix what we’ve done. The long answer involves a lot of planning and problem solving. Ultimately, it comes down to environmental conservation, as well as the safety of species both in captivity and in the wild.