With a familiar vigor he asked,

“What do you want to work on today?” He almost always says the same thing. I often wonder if he recycles these phrases with all of his students. I replied,

“I have new music today.” I sounded prouder than I had planned for. He looked pleased. It’s always fun to start new pieces. I think of it as a first date that you know won’t be too weird. This man is smart. I want to call him brilliant, but I’m not sure if I even know what that means yet. He has a wealth of knowledge that one can’t help but admire and respect, but I wasn’t sure that he would know these spirituals. They were by Black contemporary composers.

I placed the music on the piano and as walked around to other side I could hear what sounded like the beginning of a sigh fall from Prof. Short’s lips. It was subtle. Unchanged, I found my singing position. He began to play the first spiritual, “Lil’ David”. I love this song. Evelyn Simpson-Curenton set the text so playfully. Her use of persistent motion in the accompaniment and rhythmic surprises ensures that the most simple of text will never be boring. The song came to an end and without a word Prof. Short swiftly removed the music from the piano and began to read. He was reading the notes that the composer had written. Splinters of mumbled words buzzed through the air as he continued to read. Finally words I could understand,

“Well that’s insulting!” he exclaimed. I thought quietly to myself. What? Was he serious?

We started the next song. This one more subdued and intimate than the first – “Balm in Gilead”. I don’t know a single soul that doesn’t love this song. It has a way of becoming a spiritual event rather than a musical happening. I was fully prepared to have church with this one, but the usually expressive and interpretive Prof. Short played the piano as if he had a hang nail on every other finger. His playing lacked its usual inflection and he never pushed me to make more intelligible decision. You’ll know when he likes a song because he has a habit of groaning along with the contour of the melody, but he was dead silent this day. I sang as best I could, given the circumstances, but at this point I kind of wanted things to be over. I got the impression that he just didn’t like my musical selections.

We probably went through two more before stopping. It was only upon the final note of the final spiritual that Prof. Short said,

“Oh, well that one was nice.” Before he uttered those words, I could have convinced myself that this was all in my head – that I was being overly sensitive, but in saying what he said he basically communicated that the others weren’t good. I had no way of preparing myself for the wave of confusion that was to come over me. I was frustrated and disappointed. I was slightly disenchanted and outright offended. I had chosen these pieces so carefully. I had lived with them for weeks. I looked up the composer and listened to their compositional styles. I watched interviews of them. I wanted to know them, because I wanted these songs to represent me.

Prof. Short had nothing against Negro spirituals. In fact, he told me that he loves many of them – just the traditional ones. The boom-chuck-boom-chuck, hoedown, out-in-the-field kind.

I pride myself on my taste in music, so I’m sure that some, or most of what I was feeling was a result of a respected figure not liking my taste in music. That’s fine, but there was this other feeling that I just couldn’t shake. I walked out of that room feeling like I had been stripped of something and I just couldn’t put my finger on it. Day-in and day-out I walk into that building and I go to class. I sit there with 15 to 20 other people and we learn. With names like Jean Baptiste Lully, Monteverdi, Cacini, and Gluck, zooming by my mind’s eye, I’ll zone out and wonder, “Where are all the Black people?” We can’t pretend that they weren’t there, can we? Don’t get me wrong, there are times were we pop up, but it’s usually when we get to Jazz or spirituals. And if we do ever get to that point, it’s a pretty short unit.

For almost four years I have been singing music by all of these great composers. I mean it. They have been great composers, but they aren’t faultless creatures. Sometimes, they write not-so-great music – these are what Prof. Short calls “throw away songs”. These are the songs that you can sing in a performance if you wish, but you have to pair them with something to make it better; similar to an okay bottle of wine that needs to be paired with an herb infused sharp cheddar or goat cheese and chocolate chips. These songs just sound better in a group. I have few like that, but even the throw away songs got a better response out of him than the spirituals. It was as if my spirituals were a step below that. To him, they were below the throw-aways.

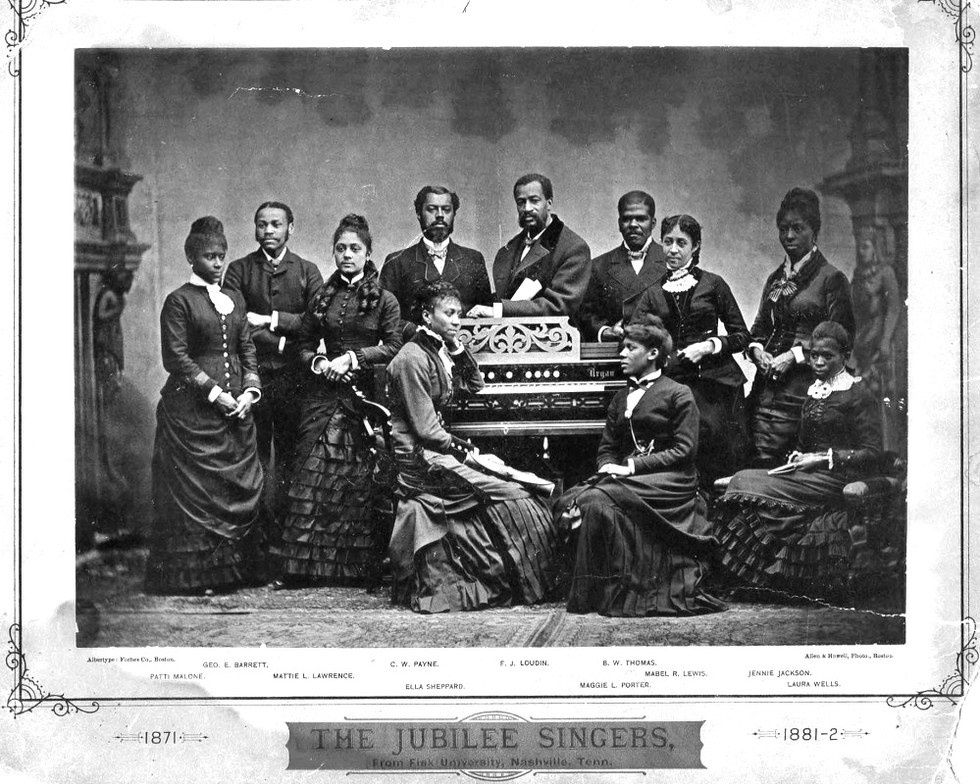

I’ve chosen not to sing Negro spirituals during the course of my undergrad for a very specific reason. In a world dominated by white faces and musical voices there is a very limited window of opportunity for learning about the Black tradition. What I know about the art form has been reduced to what I can gather from my Black upbringing, church and watching those who have come before me – scholars like Roland Hayes, Paul Robeson and Paul Adkins. It has always been my stance that being Black is not the only qualifier for singing Negro spirituals. In fact, it’s extremely arrogant to think that way. One of the greatest offenses we can commit against the Negro spiritual tradition is share an ill prepared and disconnected spiritual with an audience. Conversely, it is of the highest honors to share the voices of the voiceless. The fact that we have documented spirituals to sing at all was a feat in itself.

African slaves were never supposed to be human beings. The cognitive dissonance that European and White Americans faced was so great that they came up with entire social and religious theories to justify the enslavement of a people. Africans were a “Godless” people. They were small-brained, moral-less, and lazy. They needed to be beaten into submission. Their instruments needed to be taken away. All traces of their “heathen” life erased. The African family needed to be separated – not because it was the only way, but because they were a resilient people. They were the ones to replace the beat of the drum with complex hands claps – singing to the tempo of the work they had been forced to do from sun-up to sun-down. They were the ones to maintain the ‘call and response’ structure of their former lives. They were the ones to maintain the improvisatory elements of the music they once sang continents ago. Even though the right to conscience had always been at the core of Americas existence, that type human courtesy was never meant to been extended toward the African slaves. The two edged sword of the Americans was melted down and used for shackles and chains, and what was left over was rammed down African throats. As resourceful and creative as they were, the Africans took the Bible stories used as weapons against their humanity and turned them into song. They turned them into songs of hope – into messages of freedom. They took that White-American, “western music”, fused it with their own and turned that into the precursor of the Blues and Jazz and modern Gospel.

If I’m being totally transparent, at the core of my offense was my own residual guilt. I felt guilty for existing in a space where I allowed the erasure of my own people and myself from my art form. When I walked into that room with Prof. Short, I carried my music and my guilt. Singing the Negro spirituals was my way of finally curving my complacency toward Black erasure in western music. I figured out that it was going to take more than a recital to do that.