If you've taken Lifetime Fitness at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, you know the struggle. You think you'll come to college and be done with P.E. classes, but nope. You'll have to take LFIT, a mandated, one credit hour class on health and wellness. LFIT combines exercise (from walking and yoga to running and sports) with modules about different aspects of the body and health.

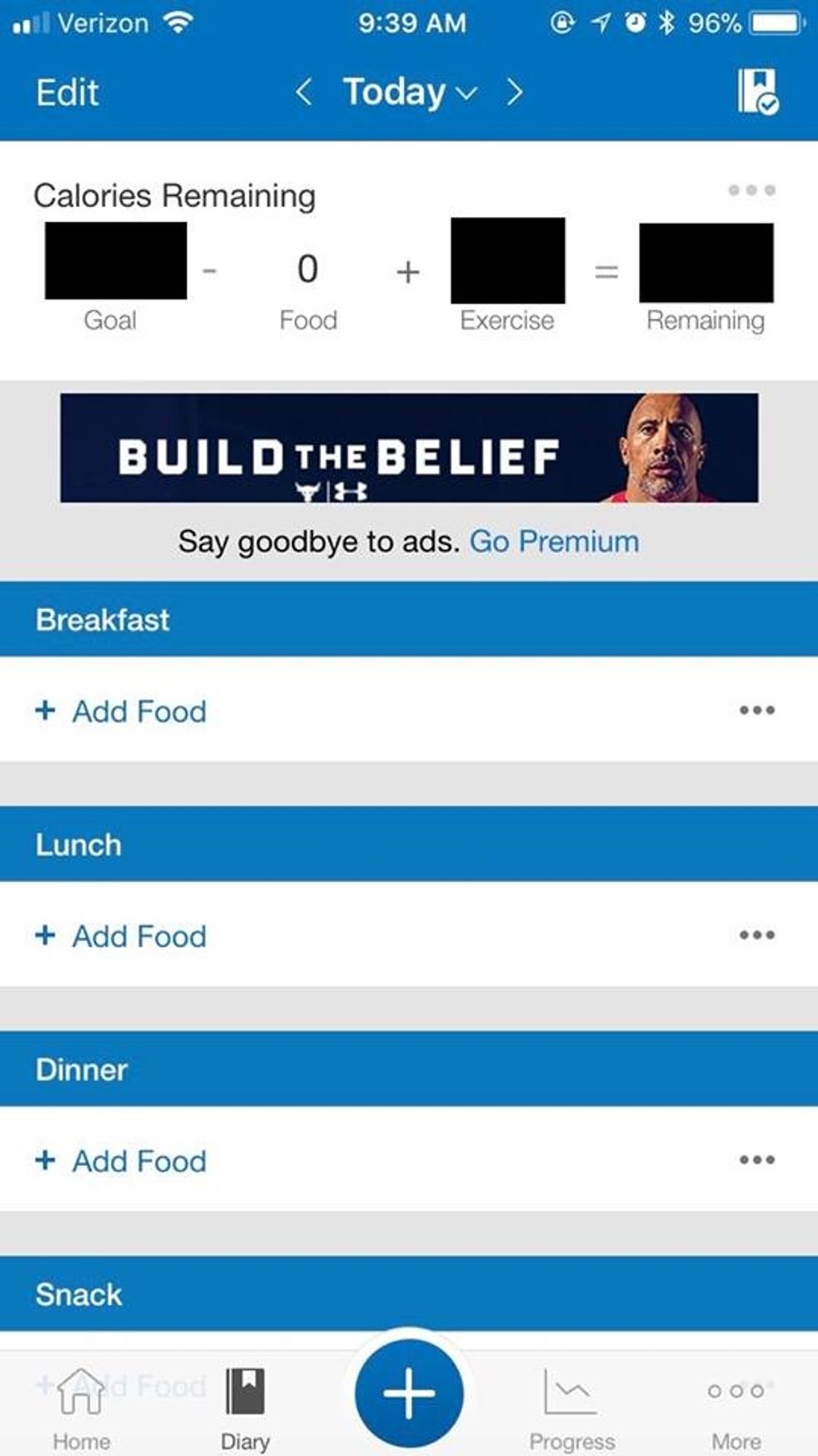

What's worse than getting up early to go run and get sweaty before your next class is the "dietary analysis unit" around the third week into the class. For this assignment, you have to track what you eat and drink every day -- including gum -- for a week into MyFitnessPal, a dieting app in which you can track your calories and projected weight loss. MyFitnessPal also requires you to say if you're looking to lose, maintain, or gain weight, and will tell you how many calories you can eat depending on your goal, as well as your projected weight loss if you eat that amount. The amount of calories you're "allowed" also depends on how much you exercise.

After the week of tracking, you write a reflection on what your diet looks like and how you can change it for the better. If you choose not to do this main assignment because you've struggled with an eating disorder, you can opt to do the alternate assignment, in which you essentially write two pages about macronutrients and how you can incorporate them into your diet. Since the graduate student teaching the class presents the alternate assignment in this way -- as the go-to option for people who have struggled with an eating disorder -- students who choose to do it instead of the main assignment have to self-identify their mental illness to their instructor, which can feel ostracizing.

I can't even begin to tell you how many ways this is problematic and for how many people, nor can I express how much hard work has gone into reforming this assignment -- but we'll get there later.

Colleen Daly, a student who graduated in 2013, experienced this firsthand. The uncomfortable feelings from the assignment contributed to the development of her eating disorder, in which exercise became an anxiety rather than an activity she enjoyed, as discussed in an Embody Carolina intro video.

She dedicated the rest of her time in college to eating disorder advocacy. In 2012, she ran for and won Miss UNC, a homecoming queen-style competition that showcases a senior woman who creates a service project that is a part of her platform. Embody Carolina was Daly's platform, her way of giving back; she wanted future students to have the opportunity to be trained on how to support friends with eating disorders. In addition to trainings, Embody Carolina focuses on eating disorder awareness, fighting stigma, and body positivity. It's now a part of the Campus Y, the Center for Social Justice and Innovation on UNC-Chapel Hill's campus.

Eating disorders in college do not exist in a vacuum. Dieting is the biggest predictor of an eating disorder, and both food-shaming and body-shaming are incredibly prominent on college campuses, fueled in part by new students' fear of gaining the "freshman fifteen," which isn't real.

Furthermore, so many inaccurate ideas about health and bodies and food exist and can sometimes play a role in the development of eating disorders and health complications from disordered eating behaviors and unhealthy weight loss. Educating people about the truth that food doesn't have moral value, that we are not good or bad people for what we eat, and that we should trust our body's cravings -- and not telling them that cancer is a disease of choice, I'm not kidding -- is undoubtedly and imminently crucial.

However, the dietary section of LFIT isn't the only problem -- the lack of a solid mental health module embodies a vital part of this conversation as well. Mental health can also exemplify a life-and-death situation, is a prominent problem for many college students, and definitely plays a part in what makes up your health, mind, body, and quality of life. Mental health issues such as variations of depression and anxiety, Borderline Personality Disorder and more have high rates of comorbidity with eating disorders, in which they feed off of each other.

While mental health and true healthy eating -- trusting your body, listening to your cravings, not judging yourself for what you eat, and being flexible with your eating and exercising -- should be discussed much earlier on in life, we must discuss it openly in college. Understanding that healthy eating is comprised of more than just fruits and vegetables and that we are not "good" or "bad" people depending on what we eat leads to a healthy, happy, and satisfying life. Those of us in Embody and the Undergraduate Executive Branch of Student Government -- with the support of the Center of Excellence for Eating Disorders, one of the most prestigious eating disorder centers in the country -- agree that healthy eating is not about calorie counts and numbers, but about our relationship with food and our flexibility surrounding it. Ellyn Satter, a therapist, and dietician has an awesome definition of healthy or "normal" eating:

"Normal eating is going to the table hungry and eating until you are satisfied. It is being able to choose the food you like and eat it and truly get enough of it -- not just stop eating because you think you should.

Normal eating is being able to give some thought to your food selection so you get nutritious food, but not being so wary and restrictive that you miss out on enjoyable food. Normal eating is giving yourself permission to eat sometimes because you are happy, sad, or bored, or just because it feels good.

Normal eating is three meals a day, or four or five, or it can be choosing to munch along the way. It is leaving some cookies on the plate because you know you can have some again tomorrow, or it is eating more now because they taste so wonderful. Normal eating is overeating at times, feeling stuffed and uncomfortable. And it can be undereating at times and wishing you had more.

Normal eating is trusting your body… Normal eating takes up some of your time and attention but keeps its place as only one important area of your life. In short, normal eating is flexible. It varies in response to your hunger, your schedule, your proximity to food, and your feelings."

Additionally, calorie-tracking apps aren't as useful as they may seem when it comes to healthy eating. Dietician Abby Langer has found that counting calories can increase guilt about eating and leave out other prominent aspects of health and weight, such as stress level, sleep, and exercise. In this sense, the dietary analysis unit and its use of MyFitnessPal isn't achieving what it's intending to achieve: a healthy lifestyle. Furthermore, many students may not anticipate the original assignment to be triggering -- like Colleen Daly -- showing that the alternate assignment needs to be revised as well.

It can be hard, unnecessary, and violating for students with eating disorders to have to self-identify. In addition, those struggling may also felt patronized, invalidated, and offended by the alternate assignment, which clearly doesn't take into account effective strategies in helping people with eating disorders achieve a healthy relationship with food, their bodies, and their cravings.

Embody and the Executive Branch are comprised of students working to reform this dietary analysis unit, as well as other parts of LFIT, into a holistic curriculum that encourages healthy relationships between yourself, your body, and health that can be integrated into your daily lives for years to come. We believe this reform is more sustainable than tracking calories, drinks, and gum every single day, and eliminates the emphasis on numbers that can trigger people into becoming unhealthily focused on what they eat and how much they exercise.

During the four years that the Executive Branch and Embody have worked on LFIT reform, many suggestions arose: focusing on dietary exchanges rather than numbers, keeping track of feelings you have after eating a certain food and why, and many more.

The Executive Branch also created a survey about LFIT for all students who had taken the course; they distributed the survey in the spring semester of 2018 and provided a space for students to express their thoughts on the beneficial and harmful aspects of LFIT, as well as suggestions on ways to improve it, such as food journaling and dietary exchanges, in which you can write your feelings and actions surrounding what you eat and work to eat foods with similar nutrition without focusing too much on numbers, respectively. Many felt that these avenues embodied a more sustainable and healthy way to understand healthy eating and a healthy relationship with food.

Thankfully, the EXSS department implemented some helpful changes -- such as leaving the scale outside of the room that everyone sits in, so people can weigh themselves only if they choose and not in front of other people -- but a lot of work with the dietary analysis unit remains problematic and needs work.

If you can't tell, I'm irritated, in shock, disgusted, and disappointed. It's 2018, and people are more than ready to help implement change. UNC and EXSS, let's do better. Let's remind our students why we have reason to hope that these crucial changes will be made, and let's keep our students truly healthy and happy.

If you believe that you or a friend are struggling with disordered eating, dieting, or body image, know that all experiences are valid and no one is alone. Consider coming to an Embody Carolina training to become a better ally, and check out www.nationaleatingdisorders.org for resources.