Moral hazard is a term coined to be used in terms of economics, insurance specifically. In short, moral hazard can be defined as the incentive to take steps to guard oneself from consequences being stripped due to a built-in protection against said consequences[1]. In regards to drug use, moral hazard applies when we recognize the safety nets society has implemented for drug users. In this article, I am specifically going to address the safety net provided by over the counter naloxone, often referred to as Narcan. There is heavy debate circulating whether or not said safety nets are of benefit to drug users across the U.S. Specifically, there is concern that they increase drug use by decreasing the incentive to take steps towards addiction recovery. Essentially, the concerns for naloxone is driven by the idea that by providing insurance to protect users from overdose, we are making drug use socially acceptable and more obtainable. In this article, I am going to argue at the views of those concerned about the effects of moral hazard, and I am going to do so with a libertarian view. In this view I plan to articulate the positives of the safety nets provided for drug users and the effect it could have on our society if we further implement safety nets such as naloxone.

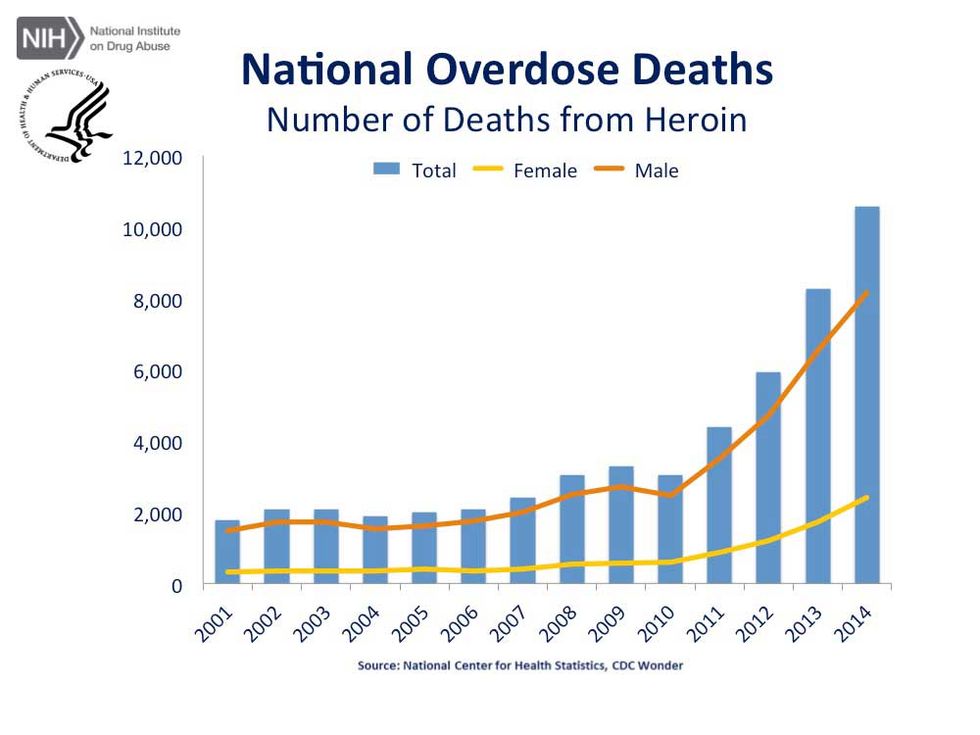

As clearly represented in the chart above, over the years heroin use has seen a large increase in the U.S. When a person is overdosing on an opioid such as heroin, morphine, codeine, oxycodone, methadone or Vicodin, the drug has attached to the opiate receptors within the user’s brain and begun to affect their ability to breath and remain conscious. Naloxone, specifically the well-known brand Narcan, essentially removes and knocks the opioids away from/ off of the opiate receptors of the brain.[2] Taking around an average of 5 minutes to start working, Narcan reverses an overdose, resetting the person's breathing, and allows the user to live. As reported by medical professionals,

“Naloxone has not been shown to produce tolerance or cause physical or psychological dependence. In the presence of physical dependence on opioids, Naloxone will produce withdrawal symptoms. However, in the presence of opioid dependence, opiate withdrawal symptoms may appear within minutes of Naloxone administration and will subside in about 2 hours. The severity and duration of the withdrawal syndrome are related to the dose of Naloxone and to the degree and type of opioid dependence.”[3]

This observation shows that Narcan removes the ability for users to enjoy the rest of their high after injection of the opioid antagonist. The user is put through withdrawal symptoms including, but not limited to, nausea and vomiting, muscle and stomach cramping, goosebumps, agitation, anxiety, sweats, racing heart, and the craving of more opiates. The level of the withdrawal symptoms and the discomfort they produce vary depending on the dependency of the user to the drug. [4]

As referenced in the last paragraph, addiction is an uncomfortable road for any person to find themselves on. Reliance on drugs in order to avoid uncomfortable withdrawal symptoms is so much more than many reference it to be. Recently, controversial opinion pieces have been reaching the mainstream media, producing much controversy on the topic. For example, with an article resulting in over 700 thousand shares, Brianna Lyman of Fordham University shared her thoughts about how drug addiction is not a disease. Specifically, she states in her article

“I’ve watched enablers cosset the addict, consistently making up excuses as to why that person is an addict, why they can’t quit, and best of all; why they have a disease and should be treated as such. But enablers are not the problem, it’s the manipulator -- who is the drug addict.”[5]

Fundamentally, this is a stance many take in order to fight back the safety nets we provide for addicts. People such as Brianna Lyman see treatment for addiction as enabling those addicted to consider themselves sick. That said, many people would also believe that someone experiencing the aforementioned symptoms is, in fact, very ill. People tend to label the choice made by users as a reason to discredit their symptoms, illness, and discomfort.

In 2016, John Tommasi, Senior Lecturer of Economics and finance at The University of New Hampshire reported,

“Within the past two years, we have seen a large increase in the number of heroin OD’s in the northeast. The reason is that heroin is being laced with the cheaper and more potent drug fentanyl. Most heroin addicts would like to quit, and the greater possibility of an OD death would normally be more incentive. However, enter the drug naloxone, sold as Narcan. Very simple, Narcan reverses the effect of the opiate and prevents death; sounds great, and by preventing a death it is. However, Narcan now becomes a form of insurance. According to WMUR/NH, drug dealers are giving away free Narcan (it’s sold over-the-counter) with every bag of heroin they sell, hence insurance and it takes away a motivation for kicking the habit.”[6]

As both a lecturer at a large university and as a police officer, John Tommasi has strong opinions regarding most subjects. In this report, it seems Tommasi’s goals revolved around the want to shed light on the question of whether or not narcan actually increases heroin use. He believes that there is a relation between the two, but would never want to remove narcan as an aid to help save lives.[7] That said, many find themselves asking a similar question. People wonder if implementing the insurance of narcan simply amplifies the idea of moral hazard leading to unsafe actions with the idea that if consequences arise, they can be reversed. If there is the opportunity to reverse the effects of an overdose, it is argued that people will become comfortable within their addiction, no longer attempting to quit their dangerous levels of usage.

So what do you think? Information all on the table, and prepared for discussion.

- Tommasi, John. "Does Narcan Increase Heroin Use?" The Economics of Unintended Consequences & Common Sense. March 2016. Accessed May 02, 2017. http://www.johntommasi.com/blog/archives/03-2016.

[2]. "All About Narcan." Narcan | Naloxone | The Opiate Antidote to Save a Life. Accessed May 02, 2017. http://stopoverdoseil.org/narcan.html.

- "Naloxone." Drugs.com. March 2017. Accessed May 06, 2017. https://www.drugs.com/pro/naloxone.html.

- Naloxone, 2017

- Lyman, Brianna . "Stop Calling Your Drug Addiction A Disease." Odyssey. April 24, 2017. Accessed May 02, 2017. https://www.theodysseyonline.com/stop-calling-drug-addiction-disease.

- Tommasi, John. 2016.

- Tommasi, John. 2016