When I think of Haiti, I think of the sea salt air mixed with dust and pollution. When I think of Haiti, I remember colorful traditional clothes bathing in the light of the sun. When I think of Haiti, I think of our remarkable history that only serves to demonstrate the perseverance and passion of my people. When I think of Haiti, I think of my father, my mother, my brother and my proud heritage. But most of all, when I think of Haiti, I think of a nation plagued by decades of suffering, waiting to be freed.

It didn’t take long for me to take notice of the suffering; it’s everywhere. It’s in the kid you go to school with that never seems to have anything to eat in his lunchbox. It’s in the eyes of the teacher who loves what she teaches, but the measly pay of a teacher in a nation so destitute made her lose the fire she once had when she started out. It’s in the father who wanted his child to be better than him, but because he can’t afford a private school, opts for the public school system that frankly doesn’t do enough to enrich these aspiring souls. It’s in the mother who can’t afford to eat and is forced to make do by eating dirt mixed with her blood and tears and hunger. Finally, the suffering is in me, me when I start to feel guilty about how fortunate I am to have the life I had.

I remember being 6 years old and deciding that simply reading my favorite make-believe books like “Les Aventures d'Alice au pays des merveilles”("Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland"), wasn’t going to cut it. So I made a decision that any sane child would: I decided to be more involved in the state of my nation. I wanted to know why there was so much suffering around me, and what I could do.

I would come home after school, after a grueling day in the city — shoes sandy white, covered in dust from the rocks on the streets, my white and yellow uniform tainted from adventures during recess, and my mind worn out often from learning another 10 sets of French verbs — and pick up “Le Nouvelliste.” My parents made a point to always be informed about current events, so it was no surprise that they subscribed to one of the largest newspapers published in Haiti. Hunched over with my 50-pound backpack and clutching the newspaper in my hands, feeling its texture, I couldn't possibly be happier in this very moment. I instantly got sucked into the world the writers at “Le Nouvelliste” have allowed the people of Haiti to explore. My eyes darted from word to word, feeling and touching every sentence — often in pain and in awe — until the very last page.

This daily routine of mine started when I began second grade, and I was 7. After enough years of doing this and feeling the cries and suffering of the nation, I set out some goals that I thought were important to change the state of Haiti. There were a lot of them, but there were a few that I knew were imperative to accomplish and needed to be done no matter what:

1. Become a doctor and provide free clinics.

2. Become President of Haiti.

3. End Corruption — punish every last government parasite official.

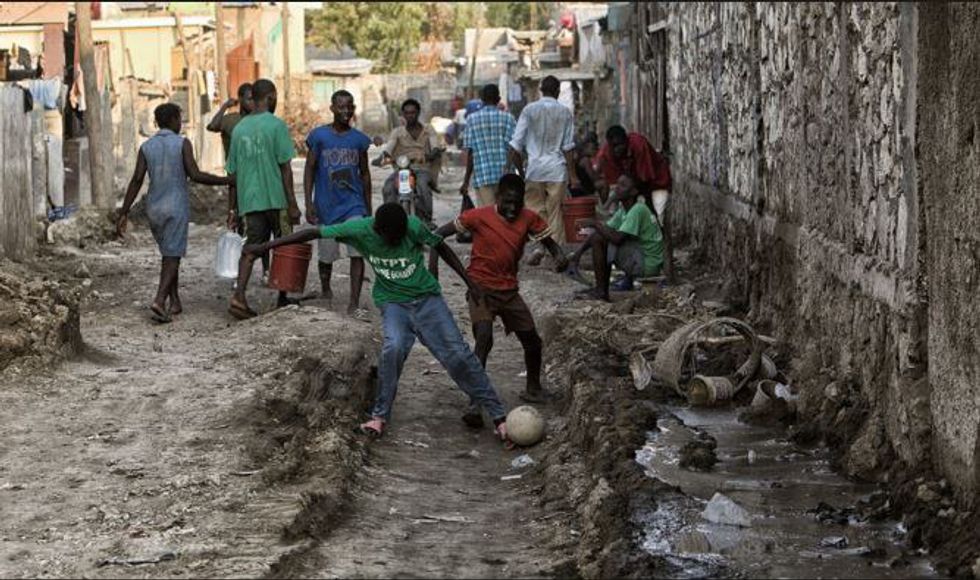

4. Systematically destroy every slum in the capital — particularly “Cité Soleil.”

5. Open up an orphanage for the children that you see every day on your way to school selling packs of water on the streets or offering to clean your car with dirty, foul rags.

6. Establish a better public school system.

Why were those particular goals so fundamental to Haiti? Why wasn’t the president — or any of his predecessors for that matter — trying to accomplish the exact same goals that a 9-year-old girl took only a couple of years to think of? As I got older and wiser, the answer to those questions became all too clear. I was determined to accomplish those goals by any means necessary, but first, I had to grow up. I needed to establish myself as a successful individual so that when it came time to put those plans to fruition, the Haitian community would trust me with their lives and future.

After I started living in the U.S., I realized the importance of why I set those goals. Kids my age who grew up here didn’t necessarily have the insight of being this concerned with the state of their country at a very young age, and I think it’s important for people to know that in a country like mine, being that young and already being concerned with things bigger than “What games should I play during recess today?” is crucial. I suppose I had my childhood taken away from me at a very young age, and I’m not sad about it. I never will be. I’m glad that I was given the opportunity to be able to see beyond the scope of a normal child.

I’ve been giving a lot of thought recently to the goals I set up for Haiti should I become President. I realized that there are individuals in Haiti who don’t want the country to be better; they’d rather see it slowly die out and suffer than help it. The poverty gap between the populace is bigger than you’d ever imagine, and to those who are at the top it means a lot — it means power. Having power allows them to continuously trample on the poor, promote corruption and, at best, manipulate elections of government officials. Should I become President, I need help. I need not only the help of fellow Haitian college students who are working really hard right now for a career that will allow them to impact Haiti, but the Haitian populace as well. I realize that after decades of promises and failures, they have lost hope. Hope drives us to not give up even in the darkest days, and they have been in the dark for so long that it is being weeded out in their hearts. I write this piece in the hopes that it will reach individuals living in Haiti right now that have lost that shining light. I want you to know that Haiti won’t always be like this. There is still hope.