I pull over onto the gravel shoulder and turn off the engine, locking myself inside of my car as junkers fly past. Behind me is Ilchester Bridge and the sound of Patapsco’s waters. On the left, across the street, are the ruins of an old paper mill. Much of the structure was scooped out after an ancient fire, leaving a field of rubble, but what was left standing is now covered in a layer of graffiti. Some of it is encouraging – “2016 IS NOT THE END” – and some, less so: “Tell me that you love Me, Even though it’s fucking fake.” The wall tells me where I’ve arrived: ELKRIDGE. I start up the car again and drive into the main part of town.

Old Ellicott City has always been a fixture of my childhood; my earliest memories of living in Maryland involve making a ceramic plate in a now-shuttered pottery place for my seventh birthday, and visiting the B&O Railroad Museum inside an old train car. Last July, an unprecedented flood swept the historical town off its feet, wiping out almost every single shop on Main Street. The town was older than the United States, but it only took a few hours of heavy rain for the waters of the nearby Patapsco River to rise fourteen-and-a-half feet and betray its inhabitants. All the asphalt on one side of the road fell away, and cars were swept up the street with people still inside them. The violent waters had peeled back layers of history, stripping emotions raw as shop owners were forced to flee from their homes and their livelihoods. Over spring break, I had the chance to visit the town for the first time since it all happened.

Although it had been months since the disaster, I was still expecting the shattered glass and three-tone alarms and personal belongings saturated with water to be strewn about the streets. I had hoped that, by drifting through the town as I would have naturally, by picking out the tiny details in what had changed since my last visit, I’d be able to pinpoint exactly what I’d lost. Then, maybe, I would be able to feel something other than the voyeuristic detachment I’d gotten from watching videos of the flood on YouTube.

My wandering ended up being a little less than natural, but I saw more of the surrounding residential area, and explored how the town is more than just the Main Street I usually see. As a child, I never thought much about those who chose to shack up in a place I believed to be so old and irrelevant to the rest of the community. But these people have a hell of a lot more resilience than I thought; in just a few months, they had managed to rebuild their businesses and homes from the ground up. It gave me a sense of pride, as if their accomplishments and recognition were my own.

In the parking lot, a group of orange-clad construction workers on a smoke break direct me around their dirt-caked equipment and over some wooden planks until I’m on Main Street proper. I start at the top of the hill and work my way down the left side of the street, making occasional detours as I go. The top-of-the-hill seems more modern, with insurance and real estate offices giving way to antique toy stores and spice sellers further down. This must mean that the more traditional stores that gave OEC its spirit were hit the hardest, so I start to walk a little faster.

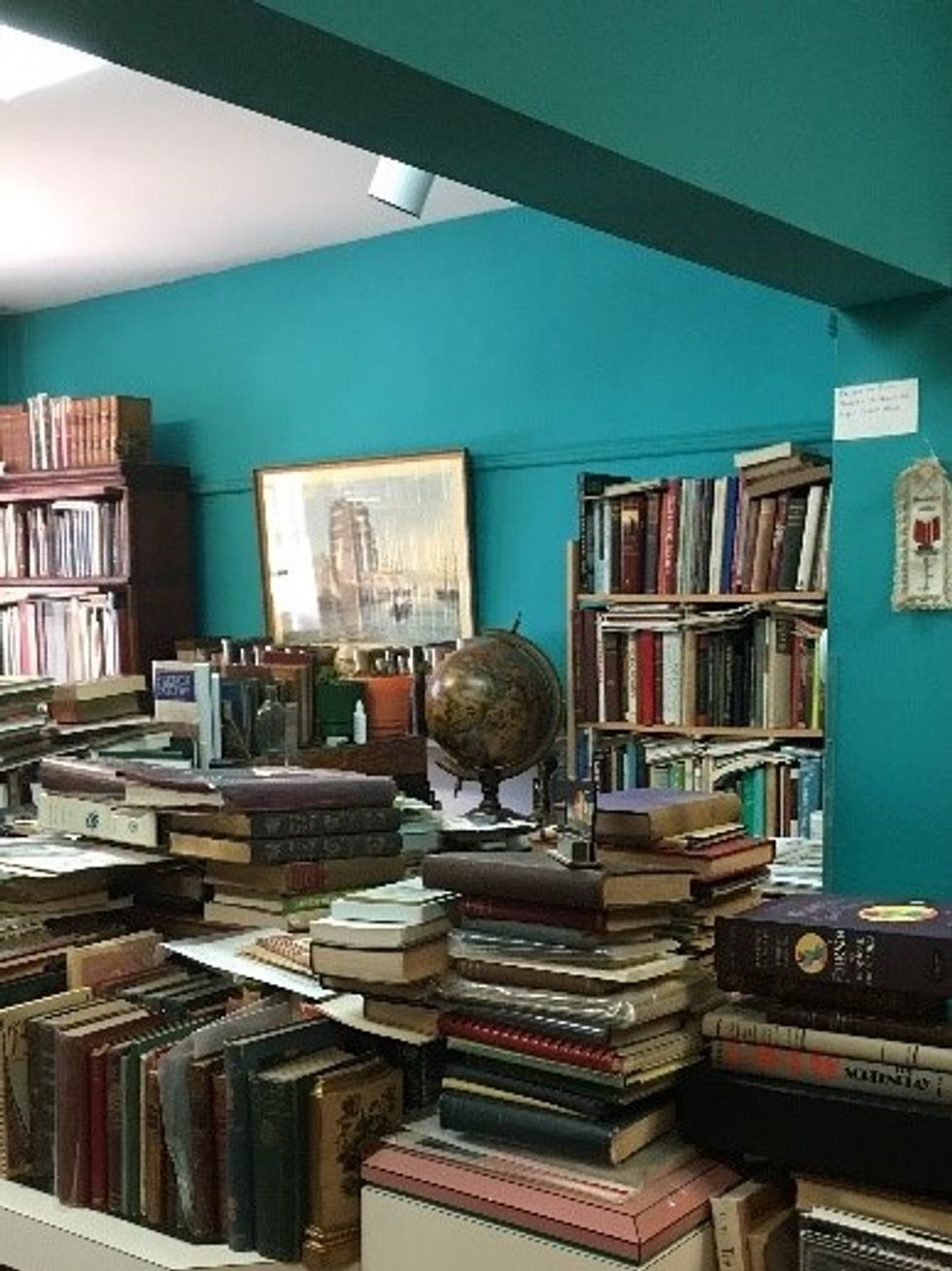

I briefly poke my head inside an antique bookstore, but I keep losing the elderly storeowner among the handwritten essays of Montaígne and stack upon stack of reinterpreted Shakespeare. He doesn’t seem very eager to talk to me anyway, so I continue down the street, passing piles of rolled-up Oriental rugs, wide-open doors and water bowls set out for passing dogs.

I am stopped by a sign: WE ARE BACK!! it shouts at me. PARK RIDGE TRADING CO. Olive Oils, Flavored Balsamics, Spices & Herbs, Local Jams & Honey. Back? I think to myself. I don’t even remember this place existing before the flood. But the doors are open and, for once, the smell of olive oil is enticing.

I look around for a few minutes before I realize that there is nothing in here I really had any reason to buy. I don’t even know how to use olive oil. I always feel guilty, though, when I leave a local business without buying anything, so I meander towards the cash register and pick out a small square of fudge and two vintage magnets I expect my mother will appreciate (which she did). I strike up a conversation with the shop owner, Donna, as she wraps my magnets carefully so they won’t screw with my debit card. To my surprise, when asked about how OEC was recovering from the flood, Donna gives me the full scoop:

Apparently, everyone on Main Street had lost their businesses (and their homes, since many lived in the apartments above), and 5% of those affected wouldn’t be coming back. Those who were temporarily homeless were sheltered and fed by the farmers’ market, or were shuffled from house to house until something more permanent was figured out. Donna and her family were lucky; she left at 6:30PM that night, before the water got deep. Her husband and son almost stayed in OEC that night to play some Pokémon Go, but decided at the last minute that they were too tired after a day at the beach. Donna then points to a sign above our heads.

“That’s the water line, there. That’s how high it got that night. Everything,” she gestures to the store I’m standing in. “All of this was gone, gutted. We lost our whole inventory.”

She quickly adds how lucky she was, though. Most of Park Ridge’s stock was shipped in from another location, so even when their wooden furniture still smelled of petroleum once it had dried in the sun, they were still able to order new ones. Some businesses had really lost everything: the men who had pulled a woman from a floating car had lost all of the framing equipment in the basement of their gallery that same night, so they had been forced to close.

Even with the changeover, Old Ellicott City’s character couldn’t be diminished; Donna flies through another story that had spread about how, in the wake of the disaster, a handful of homeless people had volunteered to clean up the garbage knotted in the grass of people’s backyards. As the woman’s eyes light up with the memory, I chastise myself for thinking that the man in the antique bookstore would have had what I had been looking for; I’m still learning that, in the real world, the best stories don’t always come from where I’d expect. Just as a quality paper blossoms from many, many drafts, the kind of experience I wanted from OEC required that I go through the process of trial-and-error with various people, places, and things. At this point of the day, the culmination of my drift had not quite hit me yet, but I was getting closer.

Ironically, Donna is interrupted by a phone call about bad credit, so I smile at her and take my leave. I reflect on how lucky I am that I can leave, knowing that these people’s lives will go on, for better or for worse, once I get in my car and drive away. For several minutes, a long train passes over the bridge marking the town’s entrance. It lends to an eerie soundtrack as I continue down the street, running my hand along the ancient rock that juts into the red brick sidewalk. A tiny sign asks politely that I refrain from climbing all over the 300-million-old structure, as if I’d be able to put a dent in it with my knockoff Toms.

Before I know it, I’ve wandered onto a residential road that climbs up and away from Main Street. From up here I can see the full effect of how Old Ellicott City has avoided death by building on top of itself; the façades that looked so jaded from the front mask absolute chaos in the back, where sleeper sofas and charcoal grills are strewn about like it’s some sort of Easter egg hunt. The apartments are squashed together, backyards and patios overlapping in some places. All I saw were a bunch of nooks and crannies to disappear into, and none of it made sense.

The sun actually feels hot today, so I decide to pop a squat on the steps of one of many churches on the residential street to cool off before my discomfort starts to show in the pits of my shirt. This church has a sign telling me that it offers free community breakfast and dinners twice a week. Across the street, a large blue-shirted woman stares defeatedly at the pile of leaves she’d swept into the plastic lid of a trashcan. I watch her watch the trash for a few minutes until she stands and empties the leaves into the can and continues dragging it up the sidewalk. I turn to look where she’s walking; the houses further up the street do look considerably nicer. I don’t care for that, so I turn back. The hills enclosing the center of the town seem designed to corral me back to Main Street anyway, so it’s not too difficult.

I make a quick round of the other side of the street, noting the discrepancies: painters on ladders and Tyvek Homewrap replace the storefronts once adorned with outdated community event posters and advertisements; the $5 tarot reading place has lost its neon sign; doors are painted over, as inaccessible as a doll’s house. I pause in front of what used to be Bean Hollow, a trendy café that got hit the hardest by the waters. I went there once with my friends in high school, and was pleasantly surprised to discover the secret drawers under the tables that had brimmed with journals and loose pages, each one telling a different story.

“I guess the owners are rebuilding it,” says a woman passing behind you to her partner. Not all of it.

Tacky dresses made for younger, thinner people float in the breeze outside a yoga store that used to be where I bought sage and spiritual stones made by the Navajo in Arizona. In the Phoenix, a nothing-special-pub that I had never even noticed before, a pretty girl with thick eyebrows tells me that she just started working here two weeks ago, when the owners reopened for the first time since the flood. Everything had to be replaced but the floor.

Some things remain unchanged, at least on the outside: Tea on the Tiber, as old as my surviving grandmother, is surprisingly intact, even with Patapsco running literally right beneath its foundation; the Chocolatier’s rearranged its layout a bit, but the wall running along one of the sidewalks across the street still has the keys and coins embedded in the cement. There are still many stores boasting of both their historical façades (and the worn bronze signs explaining what their building once was) and their modern interiors to maximize the customer’s shopping experience.

Finally, I stop in front of a toy store, which has surrounded itself with colorful spinning wheels and gentle wind chimes. A woman dressed in senior-signature all black stands among the toys, and I hear from her a single sigh.

Watching the old woman, I come to the eventual conclusion that my love for Old Ellicott City hadn’t been lost to the flood, but to my own absence. The freedom of being able to follow my feelings in such a drift gave me a new sense of place – my train of thought had essentially become physically realized, with new thoughts being triggered and old memories being anchored by the landmarks of the town around me. I hadn’t been walking in search of my own feelings; rather, it was my memories, judgements, prejudices, and stray curiosities that had been guiding me the whole time. With each corner I turned, I uncovered more of what I thought had been forgotten, with some new observations among the old, one of which I distinctly remember being: historical sites are a tricky thing, and living in one is even trickier – habitation will inevitably lead to modernization, whether inadvertent or intentional. Especially relevant when you have to go about gutting and replacing the basement of an ancient building, hundreds of years after the original builders have lived out their own lives, while you’re on your knees trying to put your own back together.

Eventually, I end up back where I started, sitting on some bench dedicated to some historically-significant person named Hogg (imagine, all that remains of your legacy is a haphazardly-constructed pile of splintery wood, an afterthought), watching the construction team guide the claw of a backhoe into a large hole in the ground. Old Ellicott City has corroded, no doubt – from my vantage point at the top of the hill, I can see the defunct, moth-colored factory visible in the distance, windows fogged and shattered. I think of the run-down, scruffy-looking teenagers driving around in banged-up cars, circling a town that refuses to die. I smile at the thought that this barely-recovered town will definitely outlive me.