When I arrived at Howard University last year, I was astounded to see white students. Not because I wasn’t used to them, but because I couldn't fathom why, with thousands of Predominantly White Institutions, a white student would attend a Historically Black University.

Now, I’ve yet to wrap my mind around the reason, but to be honest, I’ve stopped caring. My concern is with the violence and colonialism that comes with the white presence on Black campuses.

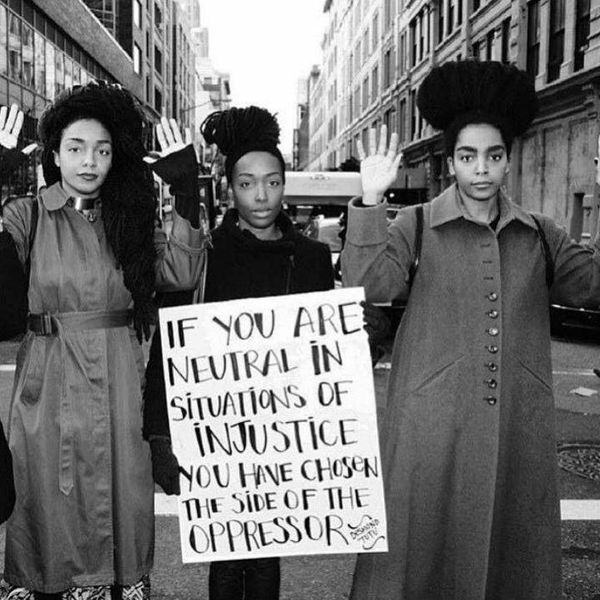

Segregation was imposed on Black people by white people, reinforcing white supremacy and white privilege. Black spaces remove this interpersonal power dynamic; they operate as spaces where Black people don't have to defend frustration with white supremacy or fear invalidation when describing oppression and racism. Black safe spaces and Black colleges are essential to resistance and healing, and when white people enter them with privilege and no context for oppression, they perpetuate racism and colonialism.

The white people at Howard are not “exceptional” white people. And I don’t say this to deny any talent or creativity they may possess, but to acknowledge that they don’t possess an elevated understanding of race relations, white supremacy, or white privilege. In my short time at Howard, I’ve encountered white students who have complained about “reverse racism,” who have defended their use of the n-word, and who have vocally contributed to colorism and to the debasement of dark-skinned Black women. The white students at Howard enter all Black spaces with the same colonial lens as their ancestors.

Testimonials from white students attending HBCUs give profound insight into their ignorance and privilege. In a Washington Post piece, one white Howard alum remarks that, living in Connecticut where “race was never an issue,” and where race was "pointed out," but "never discussed" equipped her for life at an HBCU – post-racial rhetoric directly contributing to violence against Black people. In another piece, white HBCU student, Jillian Parker, admits she’s gotten “more notoriety being so different at a place like [Howard].” Which is undoubtedly true. Just as in larger society, white people in HBCUs have immense privilege, and with this privilege comes elevation and distinction. Videos of a white Kappa strolling for his Black fraternity have nearly a million views, while videos of Black Kappas strolling have yet to garner the same attention. And it’s not just attention from peers, studies show that professors at HBCUs often “reach out proactively” to make white students feel welcome – something I can’t remember a white teacher doing in all my years at a predominately white high school.

When the roles are reversed, Black people in PWIs are met with hyper-visibility, stereotypes, scrutiny, and violence. Howard was created as a response to this kind of oppression, it exists for people who’ve been barred from all white institutions of academia – and the spaces within Howard operate similarly. The Howard pageants affirm Black beauty in a society intent upon the degradation of Black features. The Howard valedictorian speaks to Black success in an education system where Black schools are underfunded and under resourced. The Howard student body president speaks to Black political engagement in a country where terrorism, violence, and white supremacist policy have driven us from political efficacy.

So when I hear about the diversification of HBCUs and white homecoming queens, white valedictorians, and white school presidents at Black Colleges, I’m dismayed. I’m dismayed because Black people can’t have anything. We can’t have twerking, or hip hop, or the n-word. We can’t have Black fraternities, Black homecoming queens, Black valedictorians, or Black school presidents. We can’t have Black safe spaces and we can’t have HBCUs.