I consider myself extremely lucky. Growing up in Massachusetts, a state that was the first to legalize gay marriage and that had a black governor for over seven years, I have been surrounded by people, communities, and ideals that match my liberal attitudes. Indeed as a gay male living in the 21st century, I have been graced with a favorable time period to feel comfortable being myself and to not be afraid simply because of the “minority” aspect of my identity. As I’ve always felt the utmost support and love, I oftentimes forget that I am part of a minority, possessing a trait that is not shared with most of my friends, family, and broader community. Studying at Vassar College, one of the most liberal college campuses in the country, has only solidified my sense of support and acceptance, as I’m constantly with people who see me, understand me, and engage with me irrespective of my sexuality. Yet while examining my experiences so far with those of others in this country, and with the contemporary political situation in this nation, my sentience of how fortunate I am to have been born where I was and to have ended up exactly where I did has only accentuated.

When I think of myself, the first thing that comes to mind is not my sexual orientation. If I were to hear my name and were asked to mention the most prominent facts about this person (me), I would list his love for writing, his passion for science and his love for French, his unequivocal adoration of dogs, his yearning to travel, and his nearly insatiable desire to learn, grow, and create new experiences with incredible people. The fact that this individual is gay is an aside, an element of himself that must be given respect yet that is not influential in shaping his worth, and in deciding his life’s trajectory. Now I wouldn’t call myself naive, but I will admit that the events, people, and values that have defined my life so far have shielded me from the harsh reality that afflicts so many people: lack of acceptance and understanding of minuscule parts of individuals’, such as their sexuality, which in turn lead to a number of unethical consequences. People have been killed, kicked out of their homes, harassed, cyber bullied, ignored, and beaten physically and psychologically because of their sexuality. I remember one of my best friends telling me recently about her close friend at college who is gay and who comes from a family that brazenly casted their ballots for Trump; this individual felt uncomfortable and unsafe returning home, threatened by their family’s support of a campaign rooted in homophobia and non-acceptance, and to grandparents that would disown them if they discovered their grandchild’s true sexual orientation. This person’s sexuality, a part of how they identify yet a trait that has no viable influence on who they are as a person, is used against them, as a rationalization for their rejection. What I find incomprehensible is the fact that sexuality, which I reiterate is just a tiny part of a person which has no negative impact on their talent, drive, and integrity, is being used as a conduit for hatred, a hatred so potently toxic that it is splitting up families and destroying the beautiful love that once defined them, that is alienating relationships between friends and acquaintances, and that contributes to an environment where hostility, animosity, rigidity, and fear are left to fester.

This hatred is the culprit of the neglection of so many individuals not only due to their sexuality, but also due to external factors and traits such as race, ethnicity, and gender. For hatred is a precursor to injustice and inequality, leading to a deprivation of respect, comfort, safety, and overall humanity. The truth is that we are all humans, who widely differ in regard to our sexualities, ethnicities, genders, histories, and backgrounds, yet none of these facets of who we are has the ability to define our level of worth, the amount of respect we deserve, our rights, and our capacity to seek our passions and interests. I have found much solace from the Unitarian Universalist (UU) faith, which upholds seven principles that echo my personal beliefs and values. One of them is apt in this context: the inherent worth and dignity of every person. Regardless of whether one wears a turban, has dark skin, romantically likes others of the same sex, is a woman, or originates from an impoverished background, respect, acceptance, and empathy must be equally dispersed among these deserving individuals. Though many of us are rightfully proud of our minority backgrounds and unique identities, many identities are so often imposed on us by society and by others, manifestations of hatred and the yearning to create differences and subsequently boundaries between each other when none ultimately exist.

I just finished reading Ta-Nehisi Coates’ riveting and unprecedented work Between the World and Me, a captivating piece of writing in the form of a passionate and thought-provoking letter to his son, enlightening both his teenage boy and the reader with a detailed glimpse of the racial injustices on which this country was built. Coates elaborates on how America’s history of enslavement and black oppression has translated into modern society, where latent racism has arisen in the form of countless police shootings and murders, and mass incarceration rates that exhibit disproportionate numbers of blacks and minorities. The author’s unbridled language details how it feels to be in a black body in a nation built on white power, in a nation in which blacks “were people turned to fuel for the American machine,” and in which the preserved “Dream” of whites lauds American exceptionalism and white superiority. He aims to answer his self-posed question: “how do I live free in this black body?”, a question that is more rhetorical and exploratory rather than objectively answerable. Coates’ words, refreshing while haunting, were crucial for me to absorb and analyze, a white male, who is gay yet who has never really felt the negative impact of being in a minority due to my protective, environmental bubble. My lack of experience and insight into the issues faced by people who represent minorities was improved by reading this raw, first hand account from a man who grew up in fear because of the color of his skin.

One of the most poignant messages from this letter surfaces when Coates expounds upon the history of racism and the concepts of race in America. He explains the origins of racism and how it came into existence, primarily due to a desire to label and categorize humans, an unnecessary and arbitrary task. According to him, Americans see race as an irrefutable and ingrained part of human beings that cannot be ignored or neglected; it makes sense that racism, the notion of assigning innate traits, values, and proclivities to people of a certain, perceived “race,” will ensue from an inclination to degrade or scrutinize a group of people. Coates writes that, “racism is rendered as the innocent daughter of Mother Nature,” an uncontrollable, and eventually accepted force of the natural world. This concept gives individuals an excuse to be racist, a hands-off approach that rationalizes racism as an unfortunate, yet inevitable part of the human race. This immoral reasoning segues into a justification for hatred, and only strengthens the longing for people to establish identities for others to increase the distance between groups. Coates affirms that “hate gives identity,” a similar idea in that when we hate a people, we ascribe traits to them that sort them into a distinctive class, group, or grade that we perceive as inferior, and that elevates the haters above the people they despise or toward whom they are indifferent. It is natural to want to conceptualize people and objects to better understand and spatially organize them, achieving order from disorder. Yet the creation of identity from hatred is an inexcusable, inhumane, and futile attempt to find peace or order, as it leads to the suppression and oppression of a people who have been dictatorially grouped together. Race is a manifestation of the desire to create identities and underscore the exterior discrepancies between individuals while ignoring their internal commonalities.

This denial of the connections that tie humans together is a typical outcome of the hatred that individuals display toward others, which leads the haters to emphasize difference and repress similarity. For there’s an obsession to separate ourselves from what we believe to be inferior, undesirable, or irreconcilable to ourselves, and this obsession can be taken to an extreme. Suzanne Barakat, a physician at San Francisco General Hospital, reveals the unfathomable consequences of hatred in her TED Talk, in which she intimately discusses the gruesome murder of her brother, sister-in-law, and sister by North Carolinian resident Craig Stephen Hicks, which took place in March 2015. Barakat’s brother Deah, his wife Yusor, and his and Barakat’s sister Razan, were all practicing Muslims, Yusor and Razan both regularly wearing headscarves. In the immediate aftermath of the murder, police forces and other various law enforcement personnel explicated the murder as a result of an ongoing “parking dispute” between the gunman and Deah and his family, a way to evade the announcement of the murder as a hate crime against the Islamic faith. For it is too great of a coincidence that this so-called “parking dispute” coincided with the fact that all three of the murder victims were practicing Muslims, as evidenced by their external looks and cultural habits. Barakat, who has become the admirable spokesperson for her family, asserts the undeniable fact that she “is the sister of three family members who were murdered gruesomely in their homes because of their faith.” Indeed the patent hatred that drove a man like Hicks to end the lives of three smart, accomplished, and overall normal Americans, when stripped of its circumstances, is inextricable from the hatred that drove the murder of black college student DJ Henry by white police officer Aaron Hess in 2006, the senseless shooting of Trayvon Martin by George Zimmerman in Sanford, Florida in 2012, or the ghastly and unconscionable murder of gay college student Matthew Shepard in 1998. The contexts and reasons for these murders and all the others just like them vary: some impromptu, some premeditated, and some expressions of the implicit, subconscious biases that many hold. Yet they are all entrenched in a system that operates by a fear of others and a resulting, insatiable hatred, one projected onto others because of their differences that in the aggressor’s eyes render them inferior, wrong, and deserving of fear and oftentimes murder.

These murders that I’ve just mentioned are at their core hate crimes, acted out of an animosity toward people who may exhibit or represent religions, races, or sexualities that are not part of the majority, yet who ultimately possess the goals, passions, and habits that are shared by many in this country. Barakat reiterates this idea of the relations between us as humans and citizens when she states that, “what I am is an American Muslim - not very different from others who have pursued opportunities that this country has to offer.” For underlining the differences between each other is a task that only serves to complicate matters, as it refutes the fact that we are all more similar than we think and are capable of much more harmony than what our country currently emits. This past semester, I read for my global geography course an article by Anssi Paasi titled “Boundaries as Social Processes: Territoriality in a World of Flows,” in which the author discusses territorial boundaries as dynamic, fluid processes rather than immovable, physical boundaries. Boundaries for Paasi participate in three recognizable and intersecting concepts, with the construction of identity and power as two of them. Physical boundaries between nations and regions assist in the process of developing senses of identity for people that are within an enclosed space. Paasi speaks about how boundaries help individuals organize their conceptions into a coherent spatial frame, conceptions that include the people that surround them. She goes on to write that, “identities are often represented in terms of a difference between Us and Other, rather than being something essentialist or intrinsic to a certain group of people.” Here, she presents a notion that parallels how hatred contributes to the creation of identity, an identity that we perceive as foreign, different, and greatly distanced from ourselves. Surely the social construct of “us” and “other,” of “us” versus “them,” is a logical byproduct of this proclivity to categorize and demean. Paasi relates the conflation of boundaries and identities with the coupling of boundaries and power, claiming how boundaries and the sense of identity that develops from them is entangled with cultivated power complexes that prioritize certain groups, namely the “Us”, and demoralize other groups, namely the “Others”.

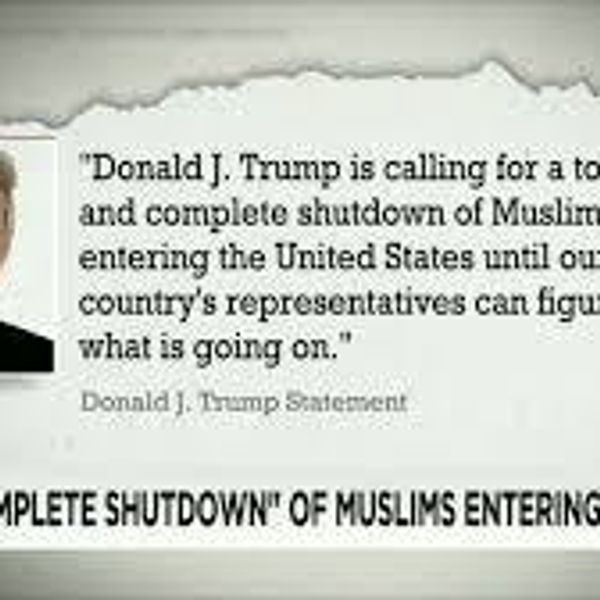

Boundaries are inscribed within our society, and extend much further than their physical location and demarcations. We orchestrate boundaries between us and other groups when we use our hatred to create identities, to create distinctions that construct invisible boundaries that prove much more powerful than one may think. And these boundaries are reinforced by the myriad hate crimes, abuses, and other various illustrations of hostility that hurt those we label, and instill us with a sense of pride and glory. The contemporary political situation that afflicts our nation demonstrates the obsession of highlighting and eradicating all difference. I don’t think anyone is in the dark about what the Trump/Pence campaign and imminent presidency promote: an enduring hatred toward Muslims and a policy to remove all of them from the country, indifferences toward the gay community, nonaccommodative and exclusionary policies toward illegal immigrants, disrespect and exploitation of women, insensitivity toward disabled individuals, the construction of a wall to bar all Mexicans from entering the country, among other extreme measures. What this has revealed is a deep-seated, lurking, and almost vengeful form of hatred that has been elicited from an overwhelming number of Americans who have extolled racism, homophobia, sexism, Islamophobia, misogyny, ableism, and other unjust ideals. The 2016 election has unveiled and confirmed a hatred that has poured out of numerous minds, and that has exploited so many minorities in emphasizing their identities as objects that need to be either corrected or dispelled. Now I recognize that supporting the Trump/Pence campaign, making racial comments, etc., are to be differentiated from the active killing of innocent civilians; I do not equate people who hold racist or offensive beliefs with those who take the lives of others, but I do concede that all of these tendencies and occurrences originate from a central place, one where hatred, in all its ugliness, and in its barest form, resides and finds nourishment.

This deep, internal hatred has been revealed on a national scale, and is redolent of the hatred displayed by the police officers mentioned by Coates; they claim in their rationalizations for killing a black individual that they were acting in self-defense and that the alleged perpetrator was on a crazed, deadly rampage. The racism that has resulted from such a refined and habitual hatred toward people of color in this country has led to a subconscious yet desperate need to preserve the flagrant imbalance of power and respect between whites and blacks in America. Coates sheds light on the trend of police procedures after each fatal shooting of a black “offender,” noting the minimal investigation of the officer and the extensive investigation, questioning, and over-the-top exploration into the black victim. “This officer, given maximum power, bore minimum responsibility,” a pattern characteristic of the numerous police shootings that occurred because of the suspect’s race. For people will do anything they can to preserve their Dream, their traditional vision of how the country should be, one compatible with the infamous “Make America Great Again” campaign, a phrase that could be logically construed as “Make America White Again,” “Make America Straight Again,” etc.

What is the cumulative effect of hatred in all of its forms and implications? The result is a stifling of so many because of who they are, because of elements of themselves that define them objectively yet that have no influence on their character, intellect, and physical abilities. While I cannot speak firsthand as to how it feels to be hated, to be looked down upon, I can report how others have felt. Feeling universally hated instills a legitimate sense of fear and unease that infiltrates thoughts, actions, behaviors, and outwardly expressed personas according to Coates, who grew up in constant fear. While the hazards facing blacks in America have improved from the tumultuous days of Civil Rights and the latter half of the 1900s, racism is omnipresent, adding a layer of fear and necessary vigilance for black individuals that does not affect whites. Coates explains the limits that his time period and suffocating circumstances imposed on him, as a section of his brain that could have been utilized for learning, growing, exploring, and making mistakes, was instead devoted to prophylactic thinking and a steady sense of fear. Indeed when we lack safety and security, we are effectively impeded from reaching toward the higher echelons of learning, exploration, and achievement. I’ve learned about Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, and the primary necessities that must be acquired before achievement and prosperity can be reached: safety and security are two of those primary needs, feelings that ensure we are in an environment where we can be our best selves and where we retain the fundamental support and the means to begin to achieve. For when we don’t feel safe, when we don’t feel accepted, we cannot be our optimal selves, as our natural task of preserving our lives and remaining alive takes precedence over everything else. When we are hated, and warranted identities that are conducive to this hatred, we are suppressed and prevented from reaching our optimal selves. It is no wonder why over 60% of LGBTQ youths feel unsafe or uncomfortable because of their sexual orientation, which explains the correlation between minority sexual orientations and inconsistent school attendance. So many minorities live with an inevitable, inerasable feeling that they are wrong and that they are being held responsible because something is inherently wrong with them, a false belief that impinges upon their self-esteem, their safety, and places their goals and passions in an unattainable place.

Most of those who know me can attest to my positivity that I strive to exude with everyone I see and everywhere I go. Don’t get me wrong, upholding this type of attitude is no easy task, especially when I’m met with curveballs like the 2016 election, and the numerous struggles I see troubling those around me as well as those I hear about in the media and around the world. My aunt Kathleen and her mottos serve as a main source of positivity for me, a woman who represented such warm and loving qualities that I turn to in need of reassurance. In my short 19 years on this earth I have tried to make the most out of my experiences and acted on all of my passions because I’ve had the chance to, a luxury that not many can report. A theme in Coates’ letter that I noticed speaks to life and its magic. He mentions how the ability to study, to learn about the world, but more importantly, the simple act of being human, awes him. “We are all beautiful bodies,” he writes, emphasizing for his son the critical realization that no matter what identity we are given, no matter the hatred that is forced upon us, no matter the stigmas, humiliation, abuses, and degrading assaults against us, we are beautiful beings because of who we are, because of our unique skin color, our religious attire, our romantic preferences, our gender, our very selves. While fear may appear to be the dominant factor in our lives, we must know that the answer is not to succumb to the fear, hatred, and arbitrary identities and associations assigned to us by others. My writing professor this past semester decided to leave my class with an empowering and comforting message, one fitting for students in a women’s studies course at a liberal arts college; she told us that “we can choose for our love to be stronger than our fear.” We fear that we will be hurt or killed because of who we are. We fear that expressing ourselves will earn us abuse and persecution. We fear that acting out and standing up will be detrimental to our bodies, and oftentimes, tragically, it is. We fear simply because we are in danger, because aspects of our bodies are used to create identities which make it “easier” to attack us. But I think there is no better time in this country and this world to stand together, to realize that hatred is among us and that this hatred stems from an incapacity to see differences, to accept them, and to realize that they do not define their possessors, to realize that differences are essential to humanity. Choosing love over fear is easier said than done, but a task that can be achieved incrementally through our relations with others; the resulting love can, I believe, radiate outward to accommodate a broader community and world.

In this article it was not my intention to liken the distinct struggles and pains beleaguering separate minority groups. I am discussing a pattern that I have seen, one in which hatred is the predominant root of the many injustices and conflicts that people face because of external aspects of their identities, be it skin color, romantic partner choice, gender, religious preference, etc. When we hold hatred, we hold aggression that nurtures our yearning to diffuse fear and pain all around us, and that ultimately perpetuates a toxic form of intolerance that impedes individuals from pursuing their passions and from feeling safe and secure. Hatred pervades our nation and our world, and many would call it inexorable. Many would read this article and my proposed solution and call me naive. Maybe I am naive, maybe my positivity is foolishly unrealistic. But what I am suggesting is more of a process, a project, rather than a foolproof solution. Hatred is inevitable, and there will always be a body who views other bodies as inferior that propels them to employ hatred and all of its manifestations: violence, murder, harassment, persecution, language, etc. Not all of these forms of hatred are at the same caliber, but they share a common inception. I believe that we must push through, that we must rise above the hatred that at times overpowers us yet that will never triumph. Coates begs his son to embrace the struggle that he faces, to realize that both the passing of time and the act of struggling, the act of prevailing and continuing despite the antagonistic forces, is key to overcoming them. After Deah’s death, Barakat has maintained her late brother’s commitment to service in his North Carolina neighborhood - she confirms: “I have a responsibility to continue his...legacy of community service, spread of love and awareness, and eradicating ignorance with education.” For education and awareness must be propagated throughout our nation, awareness of the hatred that is held by so many; Coates’ book must be read, absorbed, and shared; cognizance of the various expressions of hatred that exist, and of the aggressors responsible, must be honed; love must be concomitant in this struggle, in this process of resistance and progress. When I think of the task that lays ahead, I think back to the seven principles of UU, and in particular the seventh principle: respect for the interdependent web of all existence of which we are a part. Now a morass of hatred and struggle separates us from this ultimate goal, but I believe we slowly but surely can fill this gap, we can face the hatred, return to our humanity, and choose Love over our fear.