Four months ago I moved from the humid summer shores of Singapore to a quiet little town in Massachusetts, home of Mount Holyoke College. This is where I would spend the next four years, finishing up my undergrad, learning about myself - y’know, all the classic college things.

In doing this, I’ve added about half a planet and the entire eurasian continent to the commute between home and school. So, instead of taking the direct route back this winter break, my parents and I figured a route that would allow us to squeeze in a couple pit stops along the way. And of course - as we have done as long as I can remember - we made sure to stop by some museums.

There’s a lot to be sensed about a city by what their museums choose to exhibit. Singapore’s National Museum, for example, gives off an aura of a country trying very hard to establish its narrative as an independent nation but finding itself unable to find freedom from its colonial identity. In Copenhagen, the Kunsthallen Nikolaj, a church-turned-contemporary-art-gallery, is revealing of a generation’s rejection of church institutions and an ideological a shift from religion to renaissance.

By no means an exhaustive list, here are three contemporary art installations scattered across the globe that have stuck with me through my travels.

1. Louise Bourgeois’ The Couple at Ekebergparken, Oslo

The first installation on this list isn’t in a museum exhibit in the traditional sense.

The Ekeberg park is 25 acres of forest atop a hill, with a trail looping around it. Sparsely dispersed throughout this trail are 31 breathtaking artworks surrounding the theme of femininity. Believing that sculptures are “best experienced when they are somewhat alone,” it was the vision of the park’s curatorial team to allow visitors to experience each sculpture without the distraction of a dozen other works crammed into an enclosed gallery set up.

Alongside Dali’s Venus de Milo Aux Tiroirs and Rodin’s Eva, contemporary french artist Louise Bourgeois, perhaps best known for her towering spider figure, gets her own little feature. The Couple hangs suspended by wire rope in an isolated cluster of trees. Despite its massive size, the figures float in thin air and revolve according to the wind as if weightless and dancing above visitors’ heads.

I must admit, I’m not at all versed in sculpture, but I can respect the challenge the team has taken on in simply choosing a piece that hangs above ground. They have found uniquely organic solutions to the architecture of the park, proving that you don’t have to cement over grass to enjoy art. There’s a non-invasiveness about the way the sculptures coexist with nature. The Couple seemed to exemplify everything that the park stands for; it’s homage to femininity, how space allowed each work to be enjoyed on its own, but most importantly, the partnership between sculpture and nature. Each simultaneously challenged and added beauty to the other. The trees have to withstand the weight of the sculptures, meanwhile the sculpture is given the ultimate test of wind, rain, ice, heat. This conversation between the two elements created a new dimension with which to view the artworks, and is truly what made the Ekebergparken so incredible to me.

The park itself brought new dialogues to my consciousness. For instance, the role of private patronage in the arts, and finding that balance public and private funding of art spaces.

Ekebergparken would not be the sculpture park we see today without the sponsorship of Norwegian billionaire Christian Ringnes. Through his foundation, he personally funded the repair of the park, acquisition of the pieces, as well as donated works from his own collection. The first draft of Ringnes’ contract with the City of Oslo stated that the park along with the sculptures in it was to be a gift to the City, but the City refused because the financial burden of maintaining the park was too much for tax pockets.

Ringnes’ investment in Ekebergparken gave new life to a neglected park in danger of going to ruins. However, the park’s opening sparked controversy among the public. On the one hand, his sponsorship ensured that there would be enough money to maintain the park trails and care for the installations. On the other hand, Ringnes’ private leadership struck criticism about the intention of rich patrons; would they treat the pieces with the respect they deserved or was this just another stunt to add stars next to their name?

To which I must point to Peggy Guggenheim, a private collector who was one of the first to invest in Picasso, Kandinsky, Dali, and many other modern classics. Her patronage was the reason these artists were able to keep making art in their financial ecosystem.

Artists, imagine if all the rich businesspeople in the world, who had more money than they knew what to do with, suddenly got really interested in the arts.

Art is luxury, and for those who can afford it, let them spend.

2. "One Has to Wander Through All the Outer Worlds to Reach the Innermost Shrine at the End" at The Singapore Biennale

Courtesy of Singapore Biennale

The name of this next one is a mouthful, but is certainly accurate of the depth and density this piece invites you into.

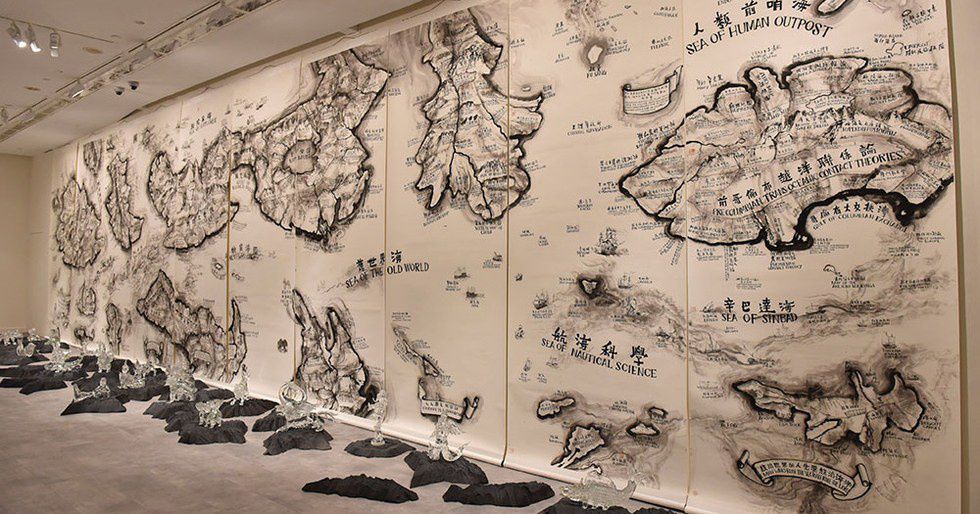

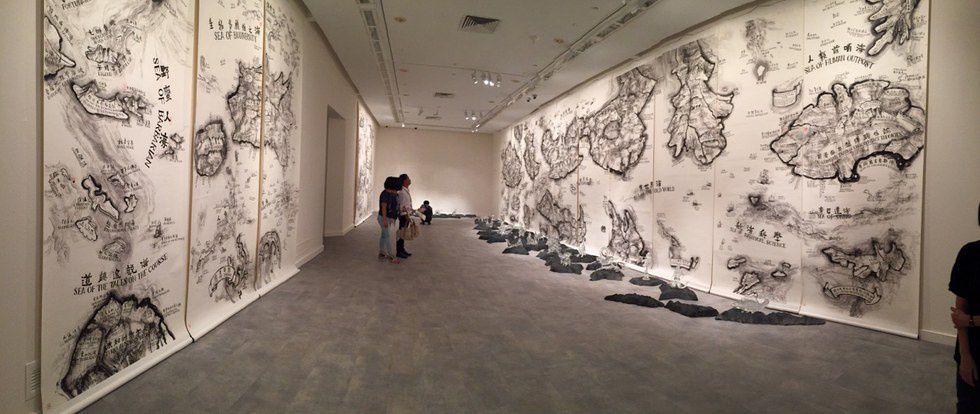

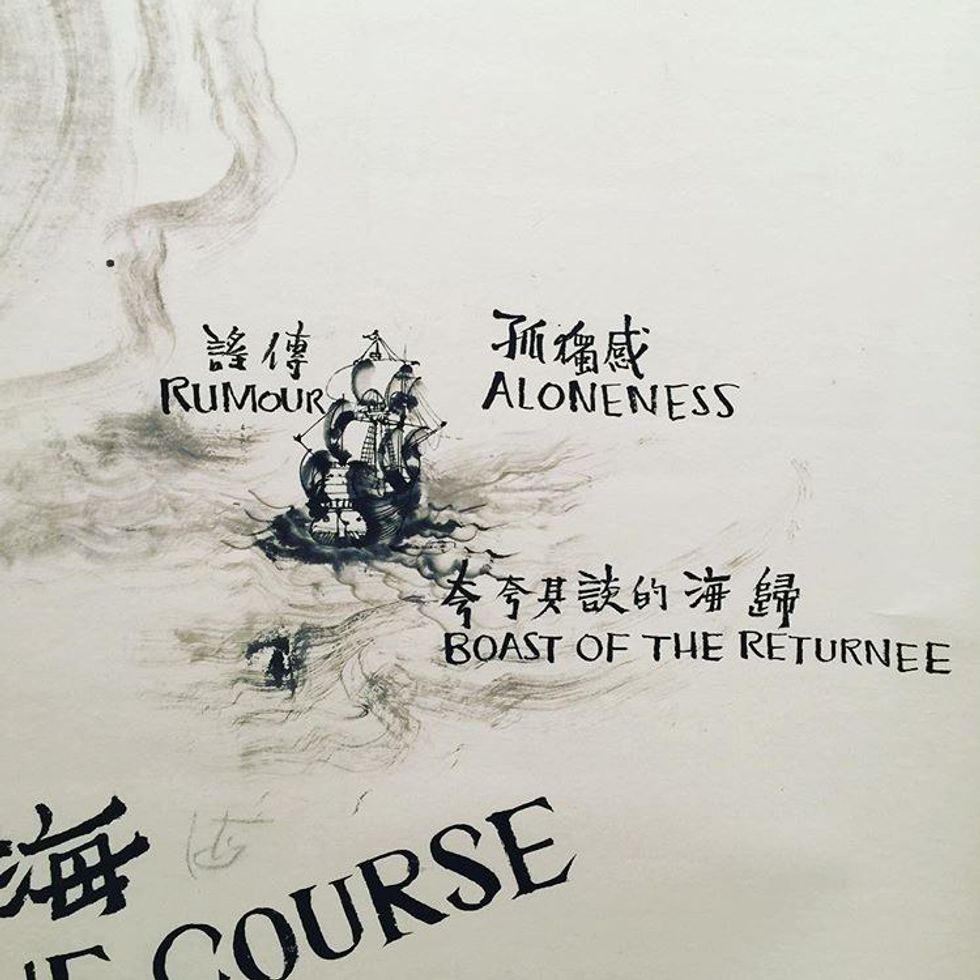

Beijing artist Qiu Zhijie’s installation consists of enormous 10-foot scrolls, covering every square inch of the gallery walls at the Singapore Art Museum. Using ink on paper, Qiu has cartographically created imaginary worlds that mapped ideological concepts alongside historical events, alongside mythology, alongside scientific discoveries. He tells the story of human civilization encompassing everything from the philosophical to the scientific.

The sheer immensity of his work is a lot to take in, every panel created with as much patience and deliberation as the next:

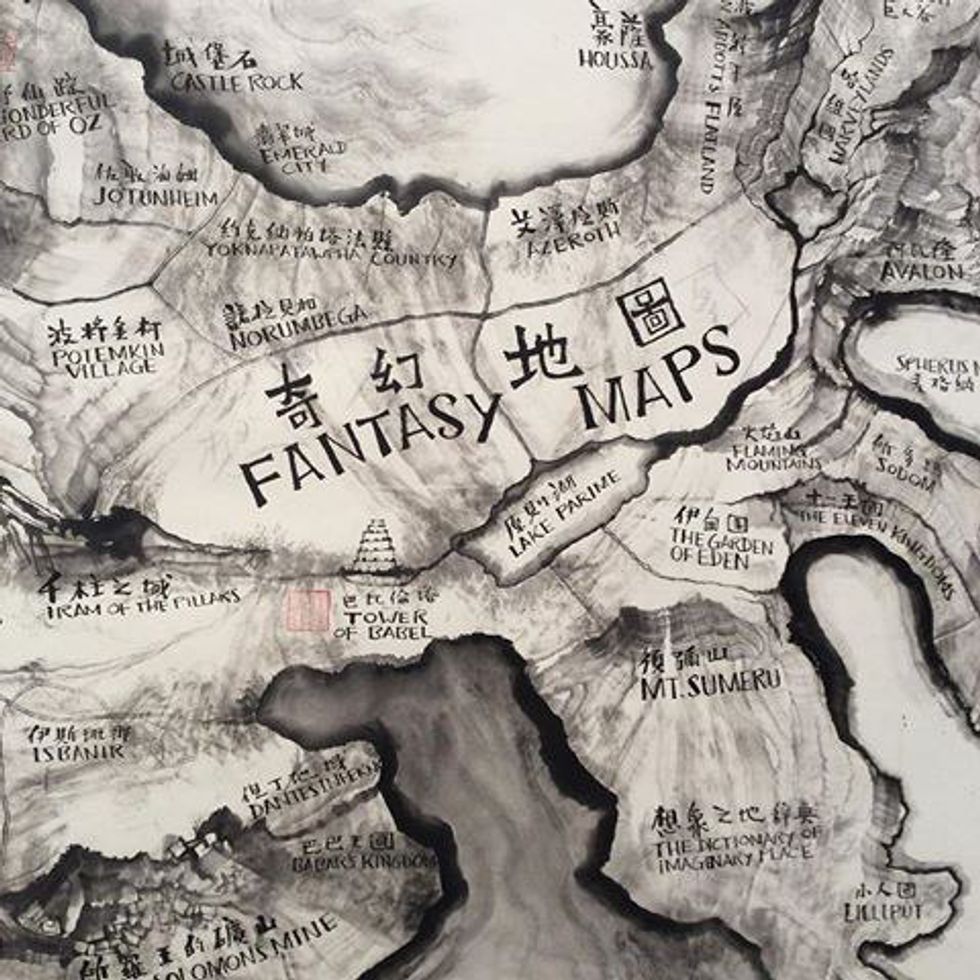

One navigates the Sea of Biodiversity and the Sea of Geopolitik; the Mount of Twelve Titans lists among its inhabitants the Golem, Frankenstein, Big Foot, and a Headless Humanoid. There is a land for Underwater Beasts including the Bunyip, the Loch Ness Monster, and the Fur-Bearing Trout. Off the coast of a small island we find the Devil's Triangle, Gog and Magog, and Apocalyptic Thinking. You get the general idea, but there are many hundreds of entries in this encyclopaedic, geographical fantasia. - John Mcdonald

He dips into history, myth, science, politics and literature to create places where, say, the Tower of Babel is right next to King Solomon’s Mines, there is an island called Mental Map, and Admiral Zheng He’s ship sails across the Sea Of The Old World. - Mayo Martin

Qiu’s work seemed to reinforce this idea that the person who benefits most from art is the artist themselves. In trying to digest his work, I am struck by the amount of study, of investigation, of work that must have come into this. Of course, as viewers we can feel the outer ripples of understanding exuded from this work, but at the end of the day, it is the artist who has dived and been fully submerged in the work.

Seeing this installation felt like looking into a personal anthropological study guide; packed with detail and correlation, but also revealing of the artist himself. His interests, for example, evidenced by a continent dedicated to the history of print, photography, and cartography, from the coastal maps used by Zheng He to the first European Mercator projection map to . Qiu's origins in China is also reflected in the depth of his approach to Chinese history and Chinese interaction with the larger peninsula. Each panel felt like peering into a page from his diary, simultaneously mapping a world as well as an individual.

Despite the impressive artworks however, I must admit I was disappointed by the curation of the Biennale. I wouldn’t be able to count the numerous times I walked into a gallery and felt like I had to stretch for an understanding of the pieces, or had to read the introduction multiple times just to understand it. It is, of course, not a curators job to tell us what to think about an artwork, but I stand by my belief that the the best exhibits are not the ones that have the most number of big names, but rather those whose intentions are clearest.

As a whole, the collection lacked unity and felt overly convoluted. With names such as “A Somewhere of Elsewheres,” “An Endlessness of Beginnings,” none of which helped to contextualize the exhibitions. It’s what John McDonald in the Sydney Morning Herald described as an “exaggerated intellectualism of the curatorial process.” The introductions beat around the bush, using smart-sounding words but not really telling visitors much about each installation.

Some of the more interesting tidbits, like how Pannaphan Yodmanee’s Aftermath was made from real rubble found on-site in Thailand, wasn’t made apparent to me until I started chatting with a museum supervisor. In an age where anything and everything can be put in a museum and labelled art, context holds an increasingly important role in creating that doorway into an artwork, and it was in this way the the Biennale fell short.

3. Yoko Ono’s "One More Story" at Reykjavík Art Museum

It was our last day in Iceland and we were hoping to hike some glaciers, but a storm breezed in and cancelled all activities for the day. Bummed, we drove to The Perlan observatory, hoping at least for a nice vantage point of the city, only to find that it, too, was closed. Double bummer.

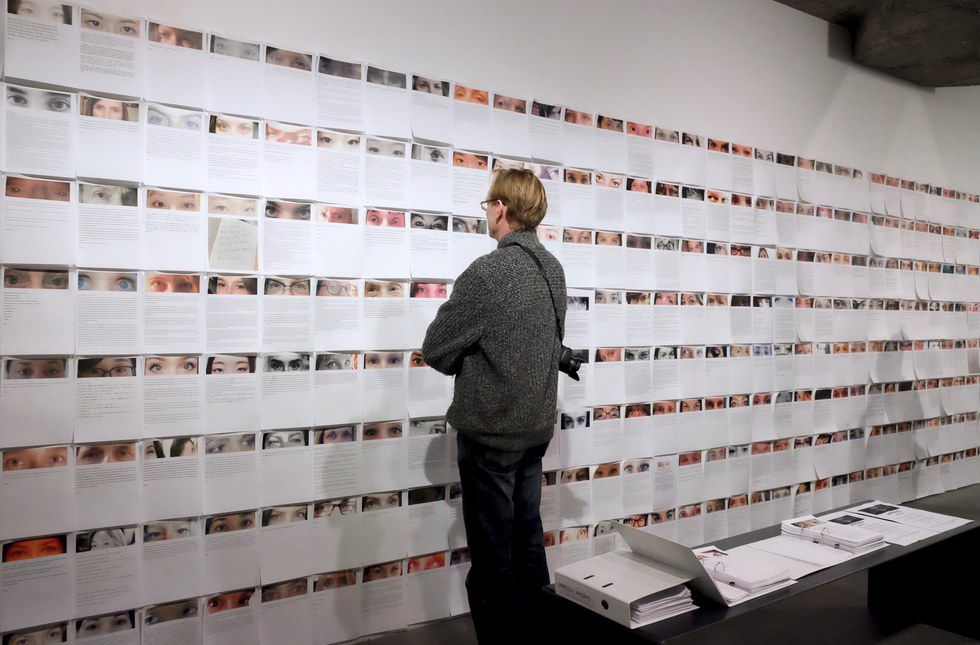

We had the whole day and little to do with ourselves, so we wandered the waking city, and finally allowed ourselves to stumble into the Reykjavik Art Museum. Without any knowledge of the current exhibitions, I made my way up to the second floor and was confronted with Yoko Ono's One More Story. The exhibition featured Arising - a wall of women’s eyes with testimonies of harm done to them - behind it her narrative works, and then behind that her instructional works.

I’ve only read about Ono’s instructional works before, I never thought I’d get to see an installation of it. Say what you will about Yoko Ono, but this was some of the most fun I’ve ever had in a museum exhibit. Helmets hung upside down from the ceiling containing blue puzzle pieces of the sky, and visitors are invited to take a piece of the sky with us.

I splattered paint, hammered nails onto a wooden canvas, walked around in a body bag, shook hands with someone through a hole, but my favorite was a table laid out with pieces of broken porcelain - plates, saucers, teacups - with rubber bands, tape, and string at your disposal to create something new out of these broken fragments.

Some made abstract sculptures out of them, others likened theirs to a cat, or an elephant, or even a little porcelain man surfing a porcelain wave. I made the dangling piece on the left corner.

There is something so punk rock about this installation, this DIY, chaotic for-the-people approach to art. You’ve already heard me complain about curators who make art seem inaccessible to the average public, so here’s an example of an artist who has embedded the solution into her own work. Ono has been quoted saying that her instructional works "eliminates the usual emphasis put on the original painting, and art comes down from the pedestal." By getting visitors to interact with the installations, we are becoming a part of it, and allowing for a never-ending transformation of the works. As long as people continue to interact with it, it will continue to evolve. Going to the exhibit 3 months ago would have been a totally different experience than going to the exhibit now.

And if nothing else, going to this exhibit was fun. It was a break from the traditional museum experience, where you would walk around a gallery, reading, looking, and just being constantly fed with information without any outlet.

Playgrounds were my favorite part of childhood, but somewhere along the way we stopped being able to justify play for play’s sake. There is merit to creating something that is simply fun. Playing with the porcelain plates, I felt like a kid doing Arts & Crafts again, and at the same time my adult brain was kept occupied with the implications of our interaction, the possibilities of interactivity today with the internet and virtual reality, the demand to be multimodal and multidisciplinary as a contemporary artist today, etc, etc.