Ah, the month of May. The time of both Mother's Day and Mayday, a day of remembrance and a radical workers' holiday with anarchist roots. For those who exist at the intersection of these topics, I thought it would be neat to share, over the course of several weeks, a series of interviews with folks who are dedicated to revolutionary work in the realm of women's reproductive health. The intention is to bridge social gaps by sharing stories and perspectives.

With this in mind, I'd like to mention that #MamasDayAcrossBars is celebrating the incredible strength and courage it takes to be a mother behind the wall each day. The Prison Birth Project is collecting messages to share with the mothers in their programs/community. Help them fight isolation and show solidarity by flooding the jail and their social networks with #MamasDayAcrossBars messages. Click the link above for more information.

Below, I've included a short piece on prison abolition found in the radical feminist publication “Off Our Backs (PDF)” from 1971.

The interviewee's name has been changed to protect identity

For the first May interview, I sat with Fiona Teresa Peabody (FTP), a prison abolitionist whose close work with incarcerated women has spanned a spectrum of programming. FTP's work is both intimate and effectual. What began as an initial intro meeting quickly became several hours of long-winded discourse that was both cathartic and informative.

Can you share more about your background, specifically in providing transformational or supportive space for incarcerated women?

FTP: I have been doing programming in women’s prisons, outside prisoner support, anti-prison and reproductive justice organizing, and studying abolition with a focus on women, trans and gender non-conforming people’s resistance for the past five years.

My programming involvement within women’s prisons have ranged from: college classes, trauma informed programming (especially domestic violence and sexual assault), theatre of the oppressed workshops, and birth and reproductive classes taught in collaboration with doulas. I started with a group doing prison programming, then I began working with groups outside the academy and several years ago I co-founded and devised programming with folks outside and inside prisons.

"Most programs within prisons are religious by nature, pedagogically conservative, or focused on addiction recovery with few exceptions. The lion-share of these programs promote individual accountability as the lone solution to issues of incarceration; in other words, people who are incarcerated should take 100% responsibility for their lives and choices, divorcing themselves from any hurt feelings, resentments or demands towards people and institutions who have harmed them. Reform projects, such as these programs, align well with the public mission of the Department of Corrections—to protect society from “bad people”, some of whom can learn to change, others whom are irredeemable (but still to blame)." -FTP

A transformative space within prison program offerings is one that shifts beyond a limited focus on personal accountability towards community accountability and critiques of the larger structural powers that perpetuate poverty, racism, sexism, cissexism, heterosexism, and ableism.

There is still room for personal growth; in fact, a lot of personal empowerment occurs when folks who have had similar experiences get together and share a common experience, like, abusive parents, abusive partners, poverty, racism, and incarceration. This is not to say that political consciousness has not existed prior to these classes, quite the contrary. But, access to conversations that allow for and support critical thinking are important for all of us, and especially for those under strict institutional prohibitions.

You identify as an abolitionist, can you tell us more about what that means to you?

FTP: Prison abolition is a scary concept for most people. I think we have to begin with an understanding that prisons have been proven to be ineffective; instead of reducing violence and increasing safety they do the opposite.

Prisons began with and continue to be extensions of colonialism’s racist and sexist hierarchies. Prisons are extensions of slavery: violent tools for policing and criminalizing race, sexuality and gender in order to make profits and maintain elite power/control over designations of racial/gender superiority.

Additionally, prisons serve to create exploitable labor by separating workers (both inside prisons and outside) from their families/communities and to weaken resistance and political organizing in targeted communities. Once we fully recognize the historic roots and modern purpose of prisons--to utilize violence to control populations--abolition becomes a more accessible conversation.

Many abolitionists agree that abolition is about imagining and working toward a better world, a world beyond punishment; in that sense, abolition is an act of love and a very revolutionary act indeed.

We talk about abolition being larger than prisons, expanding the understanding of abolition to include a pedagogical shift in human relatedness— that no one is disposable.

To me, this looks like supporting people who have been labeled disposable, doing ongoing work to uncover the ways violent state projects are growing and expanding, looking at how I have been or could become complicit with those systems of domination, and diligently working to reverse the goal of incarceration (isolation) in my own life and within my relationships, especially in conflicts, in order to find alternatives to violence, police, and disposability/punishment/shame.

Women’s prisons began as a reform project. In other words, some folks noticed that women prisoners were housed and forgotten in (sometimes) the basements or the attics of men’s prisons, and they set out to create women’s prisons with the intention of creating a safer space. Whatever original benevolent intentions women’s prisons began with was lost in the process of wielding authority over subjects deemed lesser, and simultaneously, the project was co-opted by larger structural interests looking to commodify the symbology of racist/sexist tropes like “welfare queens” or the pathological “crazy and deviant woman”. This trend is consistent throughout history: a major complaint about prisons is brought to the forefront, and suddenly, a new industry develops to capitalize on that reform, subsequently mushrooming prisons.

Women in prison point to prison and society's lack of mental, physical and emotional health care, decent jobs, basic human rights and dignity in prisons, access to clean water, and access to family.

How do you believe folks can best support women through prisoner-led (or outside) movements?

FTP: By jumping in! We need help. There are not enough people working on or in women's prisons. Working on the issue of race as it intersects with gender and class in prisons is important. I would say it is best to begin and continue with a great deal of consulting incarcerated women, their communities and families and to work alongside those who do so ongoing. Another important aspect to remember: even if a great deal of research is done with programs in other states, each prison has unique needs and conditions so taking the locale into consideration is important.

That being said, there are lots of simple ways to contribute and the need is tremendous. So, jump in where you can!

-letter writing with prisoners

-volunteering for prison programming

-educating yourself about incarceration issues + taking action

-donating to organizations working on prison issues

-donating time to anti-prison groups who need help fundraising

We discussed issues like lack of access to nutritious food, lack of child/family visitation, water quality issues, and lack of transportation for children to the facilities to visit their mothers, etc. Can you share more information on people/groups who are involved in actively assisting in these areas?

There are some pretty great groups locally working to provide resources to incarcerated families and mothers here. I am not in the non-profit world so I do not know them all off-hand. I feel bad because I have done presentations alongside them and have met some of these fantastic groups, but my head is too deep in my studies right now to be helpful in this area.

I know the Quakers often take incarcerated women’s kids for a while when they are in prison so that they do not lose their kids. New parental laws were passed that deemed a parent’s rights to be null if they were absent for 6 months or longer. Most people are in prison/ jail for longer than six months, so if they do not have family on the outside, their kids are put in the system and that does not bode well for their trajectory. Plus, it’s a major traumatic heartbreak for most incarcerated parents, negatively impacting recidivism and incarceration.

Very few, if any, are working on the toxic water issue in prisons. Additionally, there are not enough lawyers working on the violence, abuse, rape, and sexism in women’s prisons and for trans prisoners.

For the women who are at the intersection of the prison system and motherhood, what have they said their most pressing needs are? What are the challenges they face that most are unaware of?

FTP: The most pressing need is the issue of incarceration itself: long sentences that separate them from their families. Another issue is help connecting to resources and support on the outside. Those who have caregivers for children need to know what programs that they can go to for diapers, formula, preschool, parks, public programs, etc. When women get out, they need to be able to take care of their kids and support themselves financially; most public programs for welfare have been gutted. We need to create community programs because those government programs are not likely coming back in the near term. There needs to be increased access to lawyers who will help incarcerated women fight for paternal rights and other issues of incarceration.

Can you share more about what’s unique about the reproductive justice efforts and childbirth education meetings you offer?

FTP: My class is often the only space during pregnancy that incarcerated mothers get to talk about their bodies, hopes for their delivery, and to process their past pregnancies/births inside and outside of prisons. There is a midwife that visits the prison once a week; however, prisoners have reported not feeling heard or supported by hospital staff or prison admin for the most part. My position is that no one is an expert on prison birth other than the collective narratives of those who have birthed during incarceration. So, my class allows time for incarcerated women to tell pregnant mom's tips on how to survive and what to expect. It is an extremely heavy and emotional space. Many of the people in the class miss their babies terribly, or may even be worried about missing fertility windows while serving long sentences. Motherhood and "womanhood" are often the only cultural narratives offered to incarcerated women as a means of redemption, adding a tremendous complexity and weight to the space we enter in prison discussion about birth. We try to juggle these contradictory needs in a healing, supportive, and even celebratory/funny manner. We laugh a lot. As much as prisons target bodies, they also ignore them. As a result, we are usually bombarded with 20-30 medical questions up front; it can be quite funny to hear us talk frankly about vaginas in a space so afraid of them. A lot of emotion is released when a time is set aside to generously answer the concerns of people who have been denied care, there is giddiness, relief, trauma, pain, and much more.

We clap and cheer for women's reproductive labor. We cry together. And we make art.

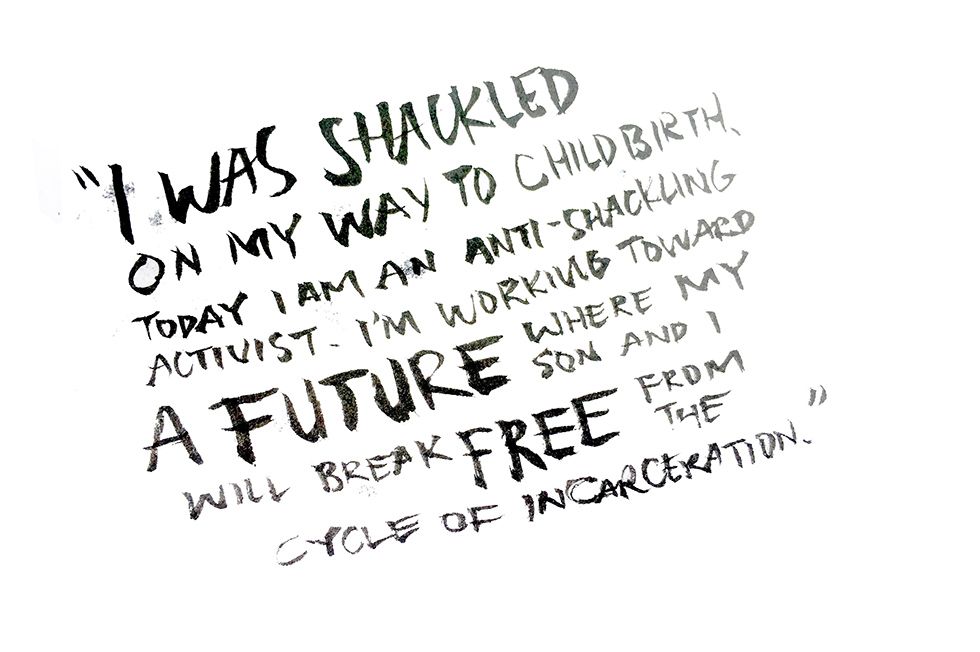

Thoughts on DOC policies or state laws regarding restraint during pregnancy/labor & birth and the lack of enforcement?

FTP: The Colorado Department of Corrections has a one paragraph section about the use of shackles in birth, which vaguely states, something like, “shackles should not be used unless necessary.” I've spoken to guards who've told me they are trained to always have one point of restraint during transfer and birth, etc. Most of the white women I have spoken with were not shackled during birth, but that narrative changes quickly depending on the race of the mother.

Most states across the nation that have past anti-shackling laws are now reporting that those laws are not being upheld, and activists are now taking additional efforts to push back and hold prisons accountable.

I think anti-shackling efforts are important. It is one measure for chipping away at violence and domination exercised against women in an already intense life experience—birth.

That being said, again, while we fight against DOC’s procedures and adherence to those procedures, we also have to keep in mind that shackles in birth are only one link in a long chain that binds incarcerated women.

People talk about the school-to-prison pipeline, meaning the ways that schools use discipline methods that target and initiate student’s track towards incarceration. But a birth-to-prison pipeline could be a more accurate lens to help us realize the boundless reach of the carceral state. I almost wonder if shackles in birth bother empathetic members of the public because it’s happening across the prison's border and into the “free world”, revealing the faulty thinking that presumes a free woman having an isolated experience of cruelty & enslavement-- a shackled birth. Prison birth projects use language like, ‘all women have a right to birth free’, but not all women are valued equally, or even as women or full humans. And that's why violence on women of color, or criminalized women, is always accelerating, because of this hierarchy of human life that designates some bodies as disposable. I think if we keep this in mind, our movements and resistance will sharpen focus and at least avoid the surprise that the system is violent, and will remain so, despite reform efforts. The system is not broken; it’s working for its intended purpose.

Shackles in birth are one part of a whole system that seeks to destroy women, families and babies. Women who are pregnant while incarcerated are forced to work grueling jobs, have poor access to health care/ food, have to climb flights of stairs to their beds, sleep on terrible mattresses, are exposed to toxic substances, and endure abuse from guards throughout term. For example, in the hundreds of hours I have spent listening to women’s reproductive traumas in prison, I have heard over and over about how they are accused of faking labor in order to get out of prison and made to wait, sitting in anxiety, alone, laboring in prison. Then, they have to put their boots on and zip up a one-piece prison assigned uniform by themselves while they are contracting. After they birth, without any family present, they go back to the prison with little to no post-natal services, and without their babies.

Shackles have become symbolic for a larger aim—all women living, birthing, and dying free. But I am afraid just focusing on this one aspect becomes cathartic; a symbolic victory for folks on the outside, rather than a sustained and substantial material difference for those whose lives have never fully been free.

Are there other programs in the US that are doing similar work that have implemented strategies you believe are especially effective?

The Prison Birth Project in Massachusetts seems to be an effective and sustainable model, from what I understand. They have a focused message and project that is entirely focused on women and incarceration, and they seem to be avoiding the pitfalls of many prison programs and projects that seek state and prison funding. Or, those programs that reach out to private institutions for funding who are also investing in prisons. I love that they are working in jails, something we need here. I think the multipronged approach is important: classes, access to the hospital, access to prenatal and postnatal visits.

This type of project would be a huge benefit here. That being said, I know a little about our local prison politics, and I know that gender responsive services have taken a recent step backwards on the priorities list. Women inside prisons will continue to strive for their rights and those of us in this struggle will continue to fight with them. There are a few people working as staff within women's prisons who are tireless warriors for programs that help women. I'm happy to talk with interested parties about those developments.

One other project: Our Love Is Unbroken By Bars. I love this project and would be very excited to see these posters pasted all over our city.

In your experience, what sorts of models or tactics are ineffective and problematic?

FTP: I hope I do not sound like too much of an elitist or an exclusionist, but I would say, any project embedded in carceral feminism. Meaning, projects not seeking to actively create alternatives to policing, prison, and surveillance. History has proven that making a kinder, gentler prison does not bode well for prisoners. That being said, successful movements require a multitude of tactics, many small steps, millions of little acts of human decency, and a mass of people (sometimes with different pedagogical orientations). We are all learning, none of us are clear of potential or actual complicity with systems of domination; that said, we do have to hold ourselves and each other accountable.

Most of the prison programs and movements I have encountered are focused on grooming/assimilating outcasts into mainstream culture. While skill building and education are important to all of us, especially for folks who have been excluded, this is not the primary blockade for incarcerated people. Liberals need to stop acting like it is.

The people in my class have incredible talents and strong desires to contribute to society but society has different goals in mind for them.

Stay tuned for more interviews in this months series including organizers behind the holistic abortion movement and other folks involved in various forms of radical birthwork. With love and solidarity, xo.