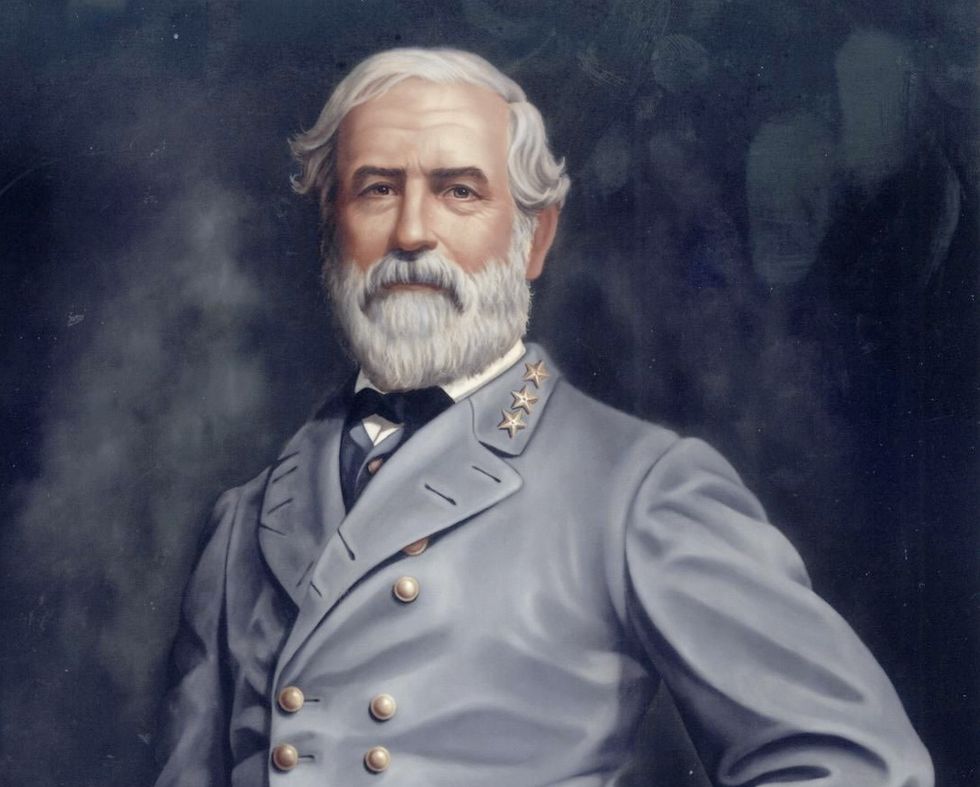

As yet another of Robert E. Lee’s statues tumble, it seems that his historical verdict has finally been decided.

Perhaps, however, “decided” is the wrong word; it implies that careful consideration was undertaken, and a true de jure finding was ultimately served. But, that seems a rather unlikely scenario. What seems more probable is that Lee was just another casualty in a long procession of dead white men excised in the name of “purging racial animus.” Of course, this is absurd – this is absurd not because the nation is wrong in continuing to root-out prejudice in all of its insidious manifestations, but because Lee is more complex than the casual Social Justice Warrior would lead you to believe.

Much of the ire directed towards General Lee is misguided at best and mendacious at worst; his history has been the subject of manifold reduction, almost painfully to the point of absurdity. His socially conscious historiographers have framed him as a pious racist, hellbent on commanding the forces of prejudice in defense of the Peculiar Institution. While the above narrative is nearly utter confabulation, it has become the predominant fiction.

In reality, Lee was nuanced. He privately and publicly had his doubts about slavery. In a letter to his wife, he candidly wrote that “in this enlightened age [...] slavery as an institution, is a moral & political evil in any Country.” – quite a heretical statement for a true racist-of-the-times and the General of the Confederate Army. But, it is true, he did not think of African-Americans as his equal. He firmly believed that the nation's slaves had it better in the States than they would have had in Africa. Furthermore, he vehemently rejected any notion of equality between the races. Yes, he was a racist.

The real question is – who wasn’t? I do not employ the rhetorical question to be cheeky nor disrespectful. I mean it. Take Lincoln, for instance. The Great Emancipator has been hailed, practically since time immemorial, as an indelible symbol of this country’s great strides towards tolerance and inclusion. Yet, Lincoln was no abolitionist. He did not advocate for an immediate end to slavery, solely halting its progression. While Lincoln was pivotal when it came to racial equality, you could hardly call him free of prejudice. When accused of being a “negro equalist” by his rival during the Freeport Debates of 1858, Lincoln retorted “I will say then that I am not, nor ever have been, in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races.” Honestly, Abe was no saint. Should we then take down his statues too? After all, who could even tacitly endorse that racists’ face chiseled into Mount Rushmore?

The problem is that Lincoln was not the only famous bigot. Washington, Jefferson, Madison and even Franklin were in no respect amenable to racial equality. The former three were slaveholders that freed their bounded neighbor only after their deaths (in Washington’s case, only after Martha’s death too). Should the founding father’s busts, statues, and monuments also be removed? Or, is it okay because it was nearly a century prior? Oh, and don’t forget to include U.S. Grant – the commander, vaunted Union General, and later President – who owned slaves until the passage of the 13th amendment in 1865, at the Civil War’s end.

If you endeavor to rid the world of Lee’s iconography, then your justification cannot rest on racism alone – unless, of course, you are willing to do so for the near totality of the nation’s most foundational figures. More reasonable claims are grounded in an understanding of Lee as a traitor. A Benedictian-esque figure that fomented turmoil and virtually tore the nation in twain. Is that not as clear as it gets?

Again, the specifics may muddy the waters. It is true that Lee was in-charge of Confederate forces, but not that he enthusiastically proffered his military acumen in defense of the Rebels. Lee was actually quite irresolute. When the White House extended the Generalship to Lee, he needed time to think. In the end, Lee demurred, though maybe not for the reason you would assume. Lee rejected the Union’s offer namely because of his loyalty to his home state of Virginia and an aversion to fighting against his “family, neighbors, and friends.”

L.P. Hartley once remarked that “History is a different country. They do things differently there.” If you measure a man's past actions in the context of the present, you will almost assuredly be doomed to mischaracterization. After all, no one is a saint, and even Mother Theresa had her demons. Lee is not one of history’s sweetest, but he is far from the quisling monster his critics claim him to be – especially in comparison with his peers and progenitors. In short, the rancor surrounding his monument is ill-placed. If anything, such hostilities are just another stroke of an in-vogue politically correct paintbrush.