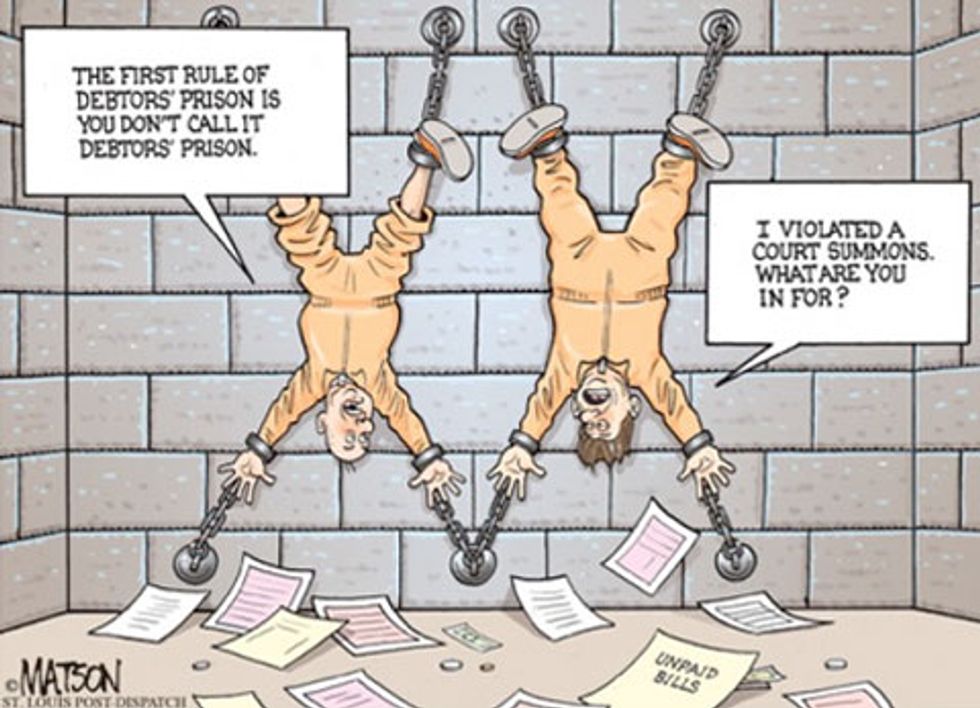

Remember back in high school in American History class when you learned about debtors’ prison? Debtors’ prison was where someone who couldn’t pay off their debts would be taken. These prisons were disgusting, glorified holes in the ground. People in debtors’ prison were not released until their debt was paid. Sometimes prisoners were allowed to pay their debt via labor though their labor was not just used to pay off debt, but to also for the cost of their imprisonment. If your family could not gather the resources to pay off your debt, you would be imprisoned indefinitely. As you may remember, that lesson ended with the relief that debtors’ prisons no longer exists, though today, the institutions are making a comeback.

Jayne Fuentes is the face of a lawsuit filed by the ACLU against Benton County, Washington. Fuentes has struggled with mental illness and drug addiction and was determined to get her life back on track after serving time in prison. Fuentes found a job and has been crime and drug-free for three years and counting though her streak may come to an end.

Fuentes, among many other people in Benton County, owe varying sums of money in LFO’s. LFO’s, or Legal Financial Obligations, are fines and fees involved in the legal process that individuals to are expected to pay back. LFO’s commonly manifest over $1,000, with no accommodation for ability to pay, and sometimes come with interest rates. LFO’s can charge for a public defender in 43 states and D.C., and in 44 states, inmates can be billed for ‘room and board’ in prison. If an individual cannot repay their LFO’s, they are sent back to prison. Alternately, the individual must pay for a spot on a work crew to labor their debt away. As of last year, one out of four misdemeanor prisoners is in jail for failing to pay LFO’s.

When Fuentes was released from jail, she had issues finding a job. Despite her employment status, Fuentes was immediately responsible for repaying her debt. Benton County profits off of resentencing prisoners unable to pay their LFO’s; Benton County receives $70 per day individual spends in jail due to debt. Additionally, resentencing occurs without opportunity for the defendant to explain themselves. "Benton County is operating a well-oiled machine specifically designed to wring money out of poor people for the county's financial benefit-- and if that means people have to sit in jail or do manual labor, so be it," ACLU-WA Legal Director Emily Chiang said. The system of LFO’s in Benton County is a for-profit operation. Just like for-profit prisons, profiting off of LFO’s creates a cycle of incarceration for those without great financial resources.

Upon initially being released, Fuentes was forced to borrow money from friends and family in order to stay out of jail in addition to taking jobs as a manual labor. Currently, Fuentes is working at a fast food restaurant, though she still does not earn enough money to pay off her LFO’s. Upon leaving prison, Fuentes attempted to find a well-paying job and live independently from government aid, though her debt forces her to remain reliant on the state while essentially working for free for the county. Thousands of people each year are sent back to prison because they cannot pay off debt to the justice system. The reemergence of the modern-day debtors’ prison is yet another testament to the broken nature of our criminal justice system, that nobody asked for. Until this lawsuit is settled, this structure will continue across the country. LFO’s are just a broader part of the corruption in the justice system, and this lawsuit filed by the ACLU may be a major success for citizens across the nation.