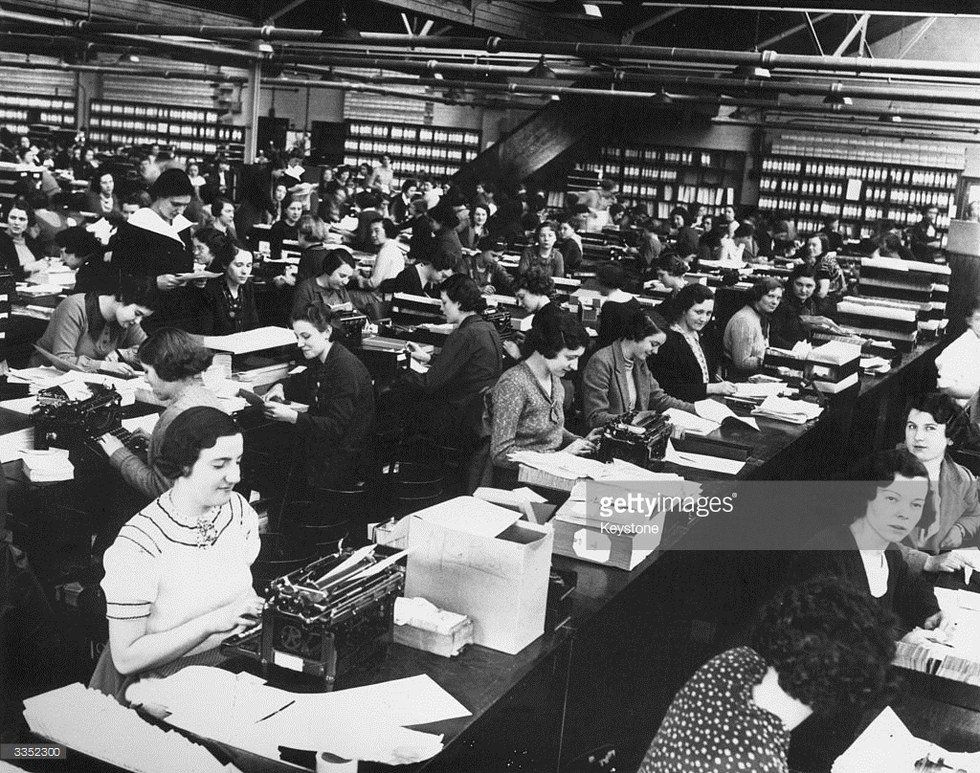

The archetype of the attractive female secretary seems thoroughly entrenched in Western culture; Mad Men is perhaps the best-known example nowadays, but the TV Tropes page for “Sexy Secretary” has many, many more examples. It may be a surprise to many of you, then, that clerical work actually began as a male-dominated profession. The process by which clerical work became so heavily feminized has to do in part with the culturally devalued nature of women’s labor in and of itself, but the rise of clerical technology and its effect on labor practices also played a large role.

The explosion of trade and increasingly complex banking practices in the Victorian era gave rise to legions of clerks. In 1871, an estimated 119,000 clerks were employed in England. A common narrative is that male clerks were a dying breed in the later Victorian and Edwardian eras, but Brunel University professor Michael Heller disputes this idea. Despite claims that wages were either stagnant or falling, male clerical workers in this time actually occasionally got pay raises, and the labor pool instead divided into primary (higher-paid) and secondary (lower-paid) workforces, largely along gender lines. Clerical work as a profession thus remained male-dominated through the end of the Victorian era. The theme Heller brings up of lower-paid female clerical workers recurs in historian Samuel Cohn’s analysis of the British General Post Office from 1876-1936 and the Great Western Railway from 1933. His analysis showed that offices with a higher need for clerks and clerical work were more likely to hire women in order to cut costs, whereas office that did not require a large number of clerks generally hired men.

However, clerical work does not owe its feminization entirely to profit-related concerns or to the perceived lesser value of women workers, as Cohn’s analysis would seem to imply; after all, Cohn’s analysis is a case study, and case studies aren’t always generalizable. Instead, the de-skilling of clerical jobs involved an interplay between (wo)man and machine. Kim England at the University of Washington and Kate Boyer at the University of Southampton have analyzed the feminization of clerical work in the US and Canada, from the late 1800s all the way to the present day. Once machines such as typewriters enabled automation of clerical labor, they posit, “new types of clerical work [became] associated with women,” and these types of work (such as typing and stenography) were subsequently de-skilled and devalued, in contrast to professions such as bookkeeping. Machines also caught up with bookkeeping in the aftermath of World War II, which caused a further division of that profession into (female) bookkeepers and (male) accountants. Nowadays, accounting software such as QuickBooks proliferates. It isn’t much of a surprise, therefore, that today in the United States, women make up 63% of accountants and auditors but only 17-23% of employees in several subtypes of finance firms. It’s unclear if the statistics to which I’ve linked include small business owners and operators who may not be CPAs, and it’s also worth mentioning that women of color are still underrepresented in accounting and related professions, but nonetheless, this distribution of numbers doesn’t feel like an accident to me.

The question is, then, why the perceived skill level of these clerical jobs has such a strong correlation with technology. I hate to drop in half a quote from a whole book, but Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri provide a crucial insight into this question in their 2000 book Empire. Tools, they claim in chapter 3.4, “have always abstracted labor power from the object of labor to a certain degree.” To that, I would add that the idea of tools as intermediaries goes both ways. Tools such as typewriters, by performing some measure of a job’s labor themselves, also abstract labor power from their users. The logical inference, therefore, is that any job involving such machines isn’t as labor-intensive as a job that has to be done by human hands or human minds--especially the latter. In a clerical context, then, machine labor thus became gendered as feminine, while cerebral labor became gendered as masculine, precisely because the presence of machines in certain clerical jobs meant women didn’t really have to do those jobs. This postulate holds true in a completely different arena as well -- the domestic sphere, also tangled up in Western culture with womanhood. Ruth Schwartz Cowan, a technology historian at UC Santa Barbara, established in her book More Work for Mother that the advent of household machines, while they may have been intended to lighten the labor load of housewives, actually ended up increasing these women’s domestic labor.

It’s undeniable that women’s labor in general has been systematically devalued throughout Western history. On the one hand, machines and technology have historically opened up some new opportunities in the clerical field to women, but that comes at a price: the devaluing of those opportunities and the women who take them. We can joke all we want about The Machines™ taking over humans’ jobs in some near-future technocracy -- but in a sense, when it comes to clerical work, machines have been giving women jobs but devaluing their labor for a long time.