Who was Millard Fillmore? If you didn't initially know that he was our 13th president who served from 1850 to 1853, you are not alone. In a study conducted by Henry Roediger, a psychology professor at Washington University, participants were asked to list the presidents from memory.

Only 8% of the participants listed Fillmore on their first try. When shown a list of the presidents' names, 65% of the participants recognized that Fillmore was a president. Even then, Roediger stated that his participants were more confident that Alexander Hamilton (not a president) was a president than they were of Millard Fillmore. Fillmore was not the least recognizable in this study. Chester Arthur, our 21st president, was only listed by 5% of the participants.

Roediger attributes this to Fillmore's unique name and the comic parody Mallard Fillmore (The Washington Post's Presidential Podcast). Much like Abraham Lincoln, one of our most famous presidents, Millard Fillmore was born into poverty, yet he rose to the nation's highest office. Why then is Lincoln so memorable and Fillmore so forgettable?

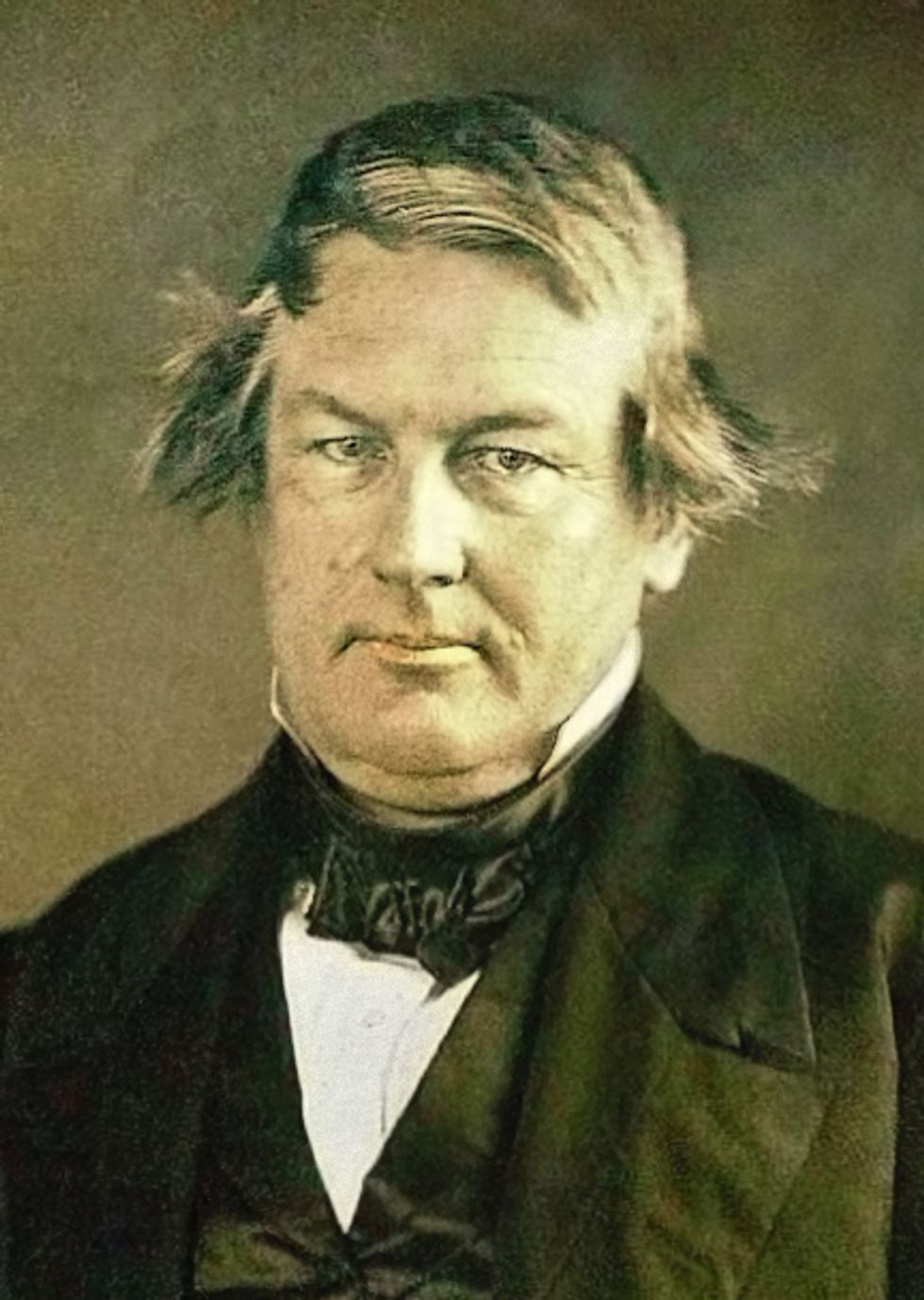

Millard Fillmore was born into poverty in upstate New York on January 7, 1800. He was self-taught except for a six month period where he attended school taught by his future wife, Abigail Powers. He began his career as a lawyer until elected to the New York State Assembly in 1829 with the Anti-Masonic Party, the first third party. In 1832, Fillmore was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, where he would serve a total of four terms.

By this time, Fillmore and the majority of the Anti-Masonic Party merged with the Whig Party. In 1844, Fillmore lost the vice presidential nomination and the governor's race in New York. Despite these setbacks, Fillmore maintained his presence in the national spotlight with his victory in the New York comptroller's race in 1847.

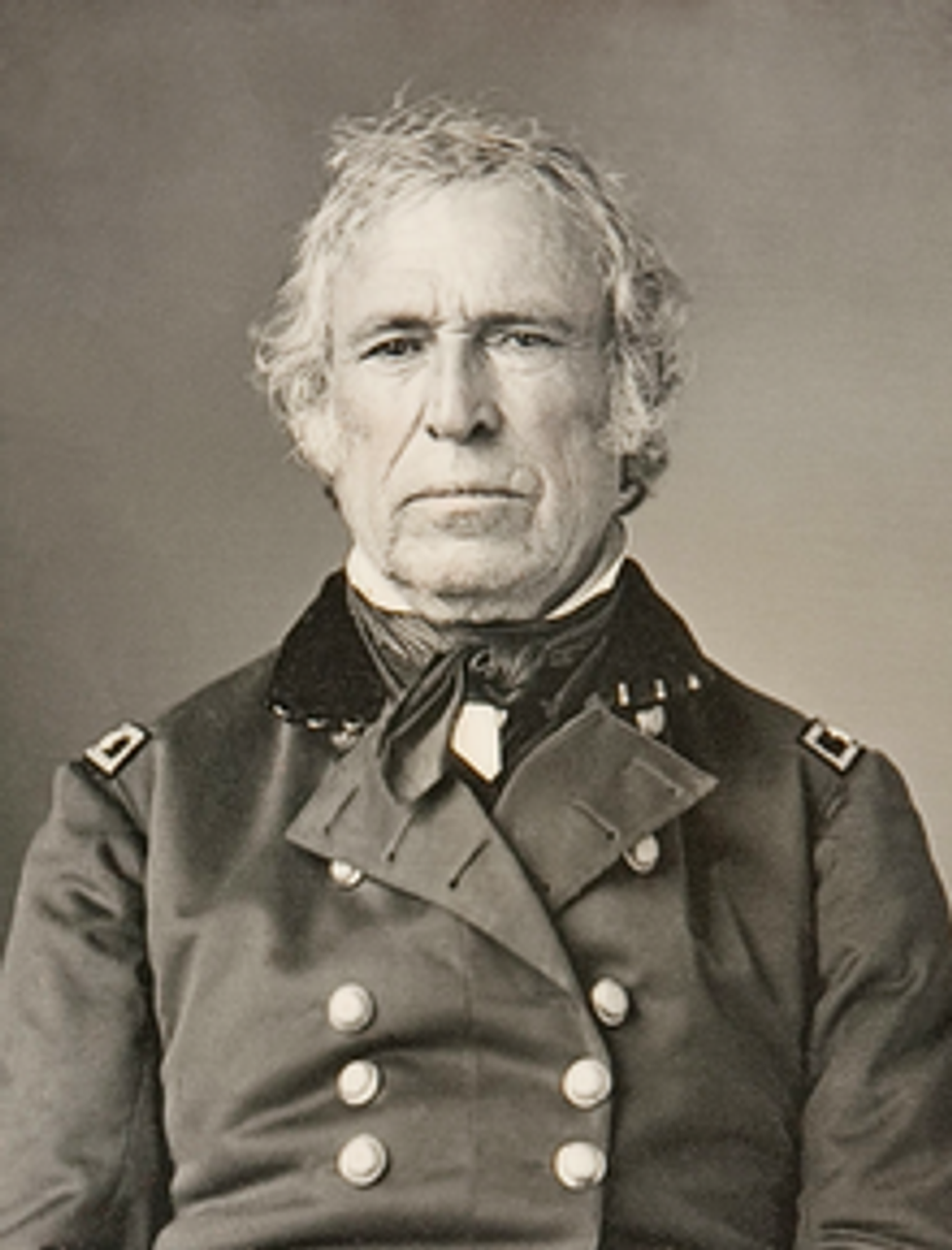

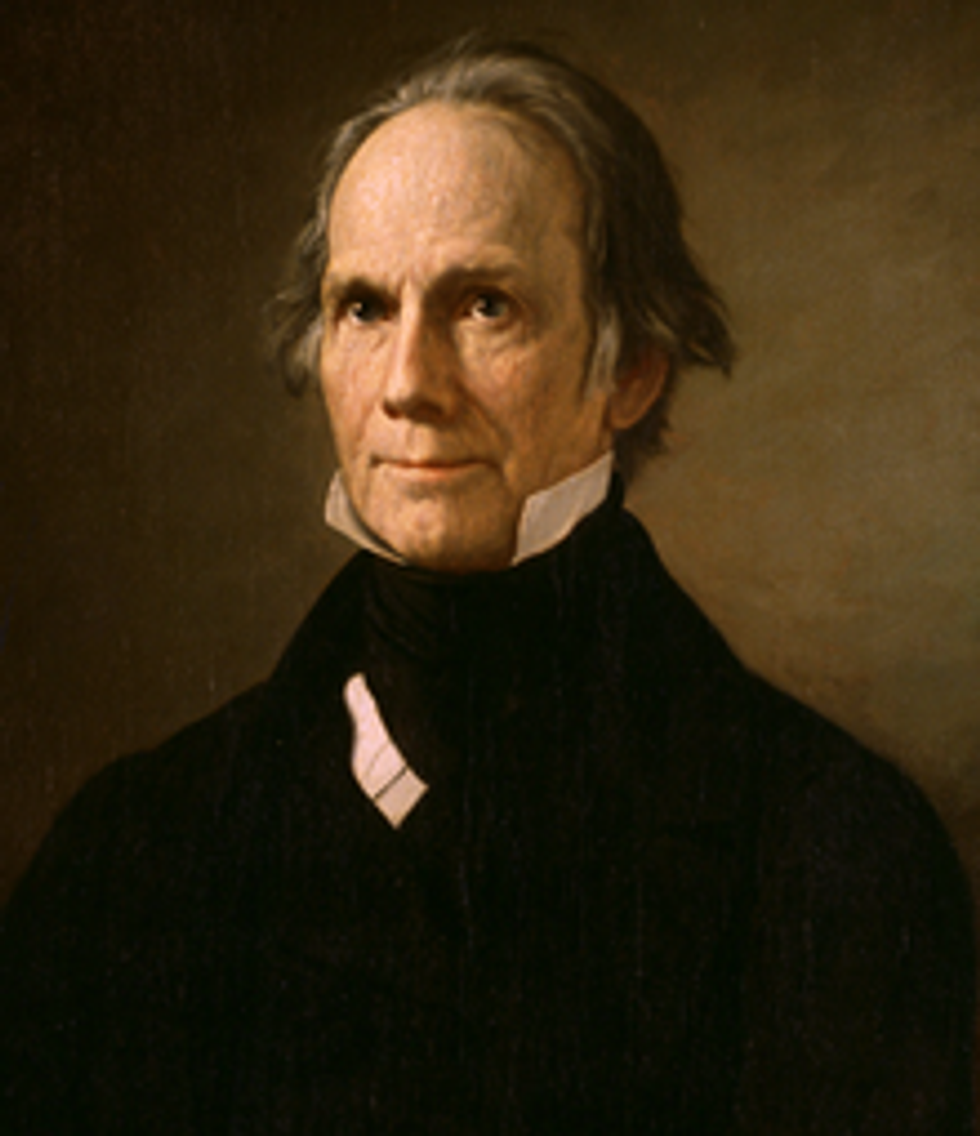

During this contentious period when politics were becoming more and more sectionalized, the Whigs and Democrats alike had a hard time finding candidates that would receive national support. The two most prominent Whigs, Henry Clay and Daniel Webster, were too unpopular in the South, so the Whigs picked the Mexican-American War hero, Zachary Taylor to run for president. Taylor was an interesting choice.

He had opposed the policies of the Democratic president James K. Polk, but had also never voted in a national election, so no one knew what his political stances were. Many northern Whigs were upset with Taylor's nomination, because he was a slaveowner, but this appealed to the southern Whigs. To balance the northern and southern appeal of the Whig ticket, the Whigs nominated Millard Fillmore for the vice presidency.

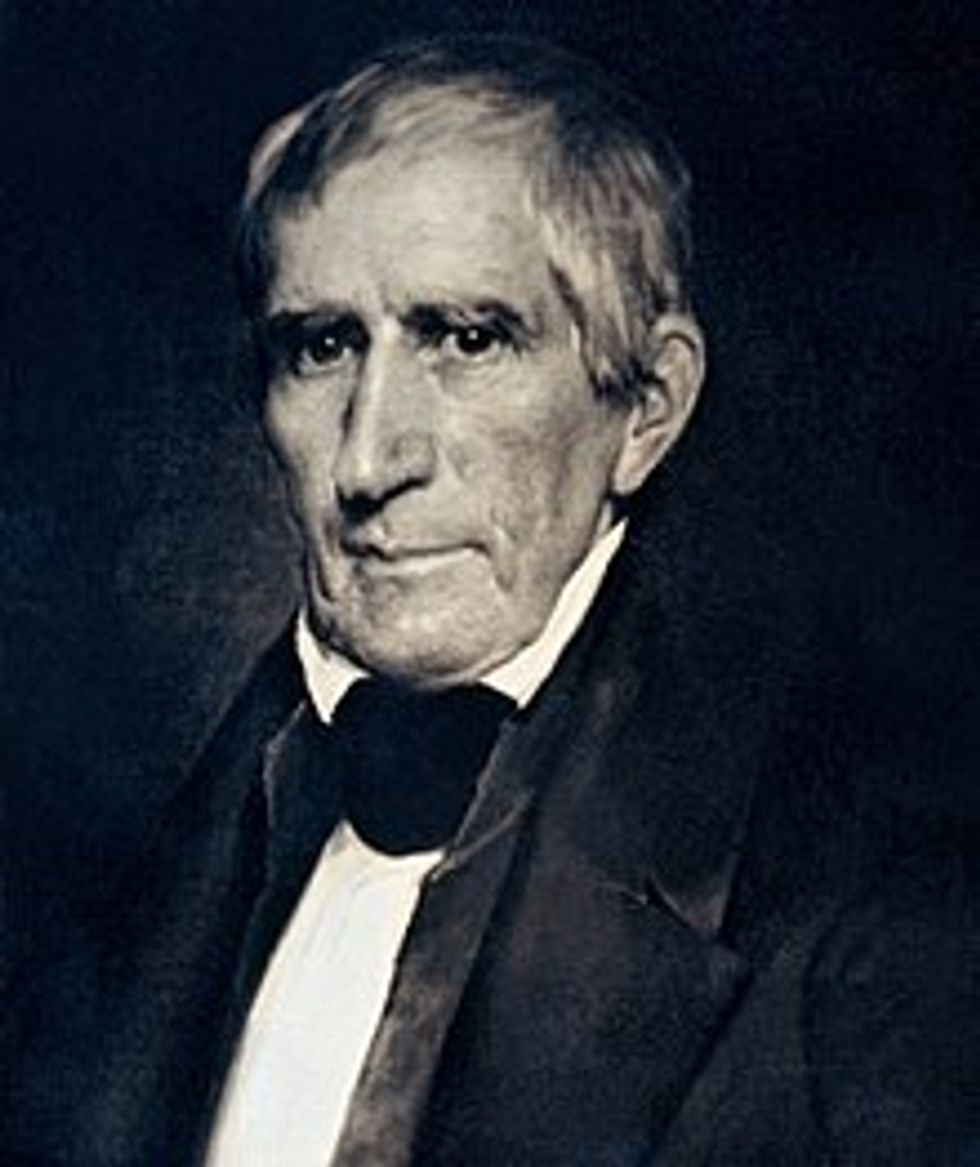

Fillmore was from a northern state and since he was a Whig for almost the entirety of his political career, it was believed he would espouse Whig principles. Taylor and Fillmore won the election of 1848, the first time a Whig won the presidency since William Henry Harrison.

Although the Whigs did not foresee the fate of Zachary Taylor's presidency, they hoped Fillmore's nomination would prevent what happened the first time the Whigs won the presidency. In 1841, William Henry Harrison, another war hero, was elected president with John Tyler as his running mate. Harrison died after only a month in office. Tyler, who was only a Whig in name, turned his back on the Whig policies once he assumed the presidency.

Hoping to avoid another disaster of an accidental president like John Tyler, the Whigs picked Fillmore. Fillmore and Taylor did not meet until after the election, and even then, they did not hit it off. Like most vice presidents of the time, Fillmore was excluded from important policy decisions, and could not even control minuscule patronage jobs.

When Taylor assumed the presidency, the biggest issue he faced was the fate of slavery in the newly acquired territory from Mexico. Under the Missouri Compromise, except for northern California, all of the territory acquired by Mexico could legally become a slave state. However, David Wilmot, a representative from Pennsylvania introduced the Wilmot Proviso, which barred slavery from extending to the territories acquired by war with Mexico. The Wilmot Proviso essentially paralyzed Congress with divisions along sectional, not party, lines. Henry Clay and Daniel Webster, jealous of Taylor's position as president, backed the Compromise of 1850.

The compromise abolished the Missouri Compromise, disregarded the Wilmot Proviso, brought California into the Union as a free state, banned the slave trade in the District of Columbia, sided with New Mexico on land disputes with Texas, and created a more stringent fugitive slave law. Although Taylor was a slaveowner, he opposed the Compromise of 1850 and intended on vetoing it if it passed. When it was believed that the vote would possibly come to a tie, Fillmore informed Taylor that in the event of a tie, he would vote against the president's wishes and in favor of the compromise.

However, this disagreement between Taylor and Fillmore mattered little, because Zachary Taylor died on July 9, 1850, before the Compromise of 1850 went up for a vote. One of Millard Fillmore's first acts as president was signing the controversial Compromise of 1850 in September, 1850 (Finkleman, Millard Fillmore).

The Compromise of 1850 was one of the most consequential decisions of Millard Fillmore's presidency. Although it is called a compromise, it is sometimes considered the "Appeasement" of 1850, because of its favorability towards southern interests. Fillmore was disgusted by calls for disunion in the southern states, but was equally disgusted by the radical abolitionists in the North. He believed that the Compromise of 1850 was the best way to preserve the Union. Unlike Lincoln, who was a savvy politician and always seemed to have a grasp on the will of the people, Fillmore was never really on the right side of populace. He failed to realize that their was a growing anti-slavery sentiment in the North, and his enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law only exacerbated it.

Fillmore can be considered a "dough face," because, although he was from a northern state, he often tried to appease southerners. For instance, he called for treason charges against a Pennsylvania men who refused to join a posse to catch fugitive slaves in Christiana, but dropped charges against southern filibusters who tried to invade Cuba and extend slavery there. One of Fillmore's biggest accomplishments was authorizing Matthew Perry's expedition to Japan. Although the expedition was favored by Fillmore, it was not completed until Franklin Pierce's presidency, so Pierce usually gets the credit.

Although Fillmore wasn't too unpopular at the end of his term, he also wasn't loved. He lost the Whig renomination to Winfield Scott in part, because his friend and Secretary of State, Daniel Webster, refused to withdraw his name from the nomination, thus withholding votes Fillmore needed to win. Fillmore began and ended his political career with a third party, running as the presidential nominee for the Know-Nothing Party in 1856. Ironically, Fillmore won the electoral votes for Maryland, which was founded as a Catholic colony, even though his party was anti-Catholic. When the Civil War erupted, Fillmore was a Unionist, who helped recruit and fundraise for the war effort.

Once again however, Fillmore was on the wrong side of politics when he opposed the Emancipation Proclamation and Lincoln's reelection in 1864. Fillmore died of a stroke in March 1874, for the the most part already forgotten. While today it definitely isn't important to know all of the intricacies of Fillmore's life and presidency, it is probably beneficial to know he, not Alexander Hamilton, was in fact a president. Even then, although he was a president, he was not a very good one. His biggest legacy is signing the Compromise of 1850. He may of thought it would save the country from disunion, but instead it drove the country closer to it.