Meret Oppenheim (1913-1985) was a Surrealist artist who transcended numerous barriers to reach her acclaimed status. Transforming everyday household items into the erotic and bizarre. Seeking to redefine the domestic life of a woman, she approached art with dreaminess, feminism, fetishism, aggression, and dejectedness. Motifs in Oppenheim's work are connected to food, sex, death, cannibalism, and bondage. Her work can get a reaction out of just about anybody.

Losing interest in her native Switzerland, at the tender age of 18 she took to Paris like many aspiring artists did. That was an unparalleled art scene, rich with opportunities and a boundless collection of minds. She would drop out of at the Paris Académie de la Grande Chaumière to advance her career outside the realms of a classroom. Networking was everything in this period. Befriending artists twice her age, she found good company with the likes of Pablo Picasso, Alberto Giacometti, Hans Arp and Dora Maar.

Rather than display as a solo artist, it was a near necessity to join an established group for a larger pull. The Surrealist group was male only, but Oppenheim's talent and charm would bend the rule in her favor. She would repay them by being a muse and model for their works.

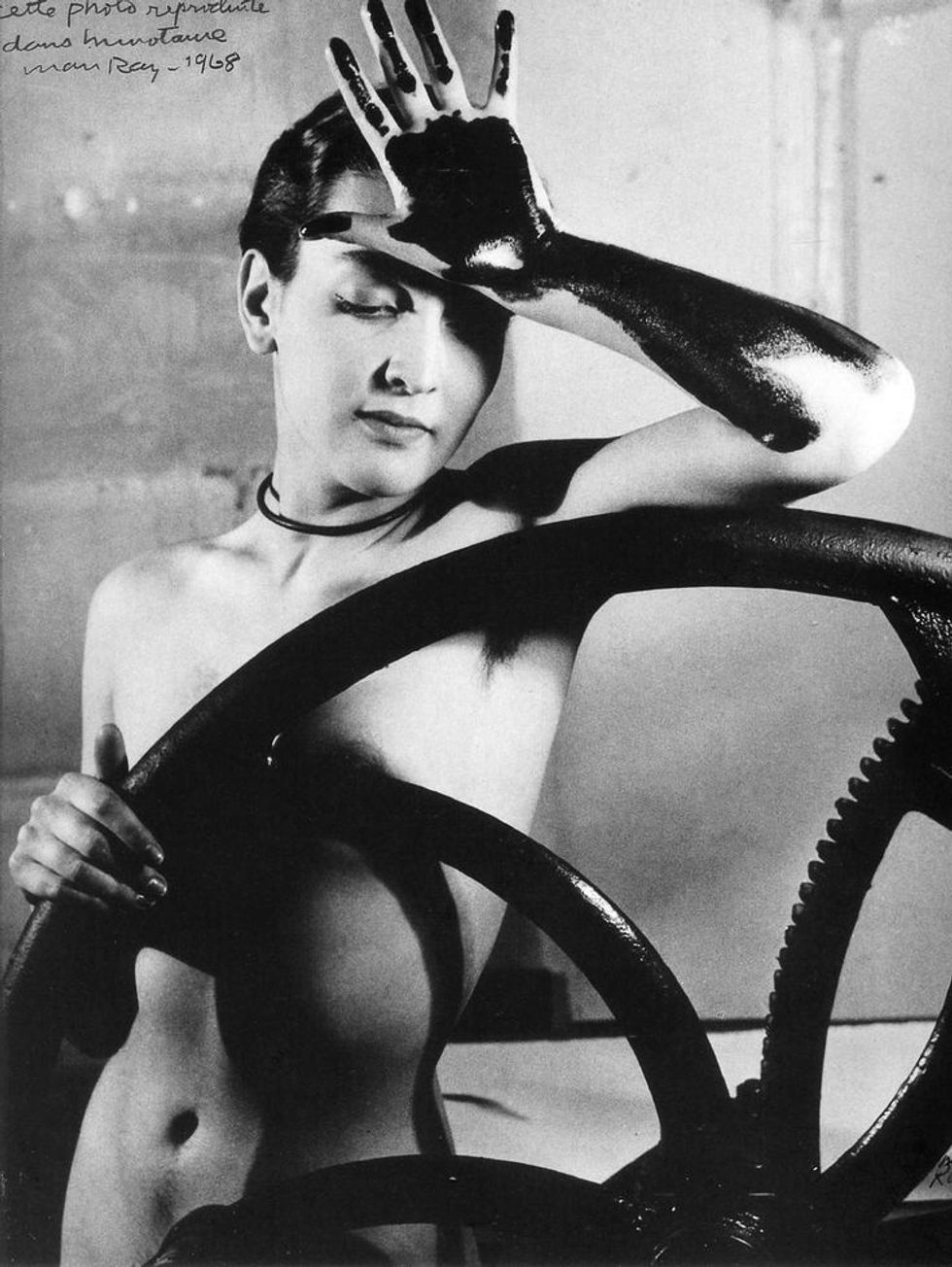

A major artwork features her as the model. Naked with a sensual, commanding pose in Man Ray's photo Erotique Voilée (1933), Oppenheim is inviting the male gaze. Published in the magazine Minotaure, scandal followed and put her on the map as a name to know.

Oppenheim looked to Erotique Voile without any objection, but unease surfaced when it came to having that included in her body of work. Despite entering on the premises of displaying her art, Oppenheim found herself in a role well-known to women: on the other side of a canvas.

Her reputation and vision would be wrapped in a sexualized lust for her by news media and curators alike that she used to her advantage but struggled to balance with her own career. An artistic breakthrough would come, thanks to the bronze high relief sculpture Giacometti's Ear (1933). It was made at the heed of Giacometti, who had encouraged her to make an artwork of him.

Fine art and fashion were seen as mutually exclusive. Oppenheim helped to shatter the barrier. Working for the 1936 Winter collection of the luxury clothier Elsa Schiaparelli, Oppenheim designed gloves. Polished nails, bones, and claws were among the take to each pair. With grey goatskin, she created the illusion of veins, turning the human body inside out and reversing the usage of gloves to conceal the body. Boundary-pushing, its sleek look was an immediate hit. The duo would team up again, with Oppenheim finding more work creating fur-covered pieces.

Even a meet up at a Paris cafe could turn into wonder works, especially in the company of Picasso and Maar. Picasso took interest in Oppenheim's fur-covered bracelet before making a quip comment that anything could be covered in fur. Brief, but impactful to Oppenheim who viewed the world with openness and imagination.

After being invited to participate in the Surrealist's first object displays, Oppenheim purchased a teacup, saucer, and spoon from a department store. She then covered them with Chinese gazelle fur. Entitled Le Déjeuner en fourrure or Object (1936), this would be her entry.

Everyday objects people mostly do not devote notice to, Oppenheim primed as her newest canvas. It draws notice to what they mean in the context of women. Its bizarreness grants a second look and new function. Making the civilized world look back on the primitive and animalistic, Object rejects the holder traditionally getting a taste. Anchored to this piece are interpretations of patriarchy.

Oppenheim would become the first woman featured in The Museum of Modern Art thanks to Object. Coined First Lady of MoMA, she reached the heights of her mentor Marcel Duchamp. Alfred Barr ensured Object had a starring role in the major 1936-37 show "Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism." Its coarse coat has remained a source of reference to modern art's timeline and Oppenheim's best-known work made at just 22 years old.

A creative crisis would shake her the following year, which art critics have tied to the hastened amassed fame she struggled to contend and surpass. It would not be until 1954 when she resumed work in the costume, jewelry and furniture sectors. From then on to her passing in 1985, Oppenheim continued to make her conceptualization tangible.

Today, she has made her mark and been subject to numerous spin-offs, discussions, and curations. Recalling her ventures as a female artist after years of personal crises and creative roadblocks, she stated in 1975, “Freedom is not given to you, you have to seize it.”