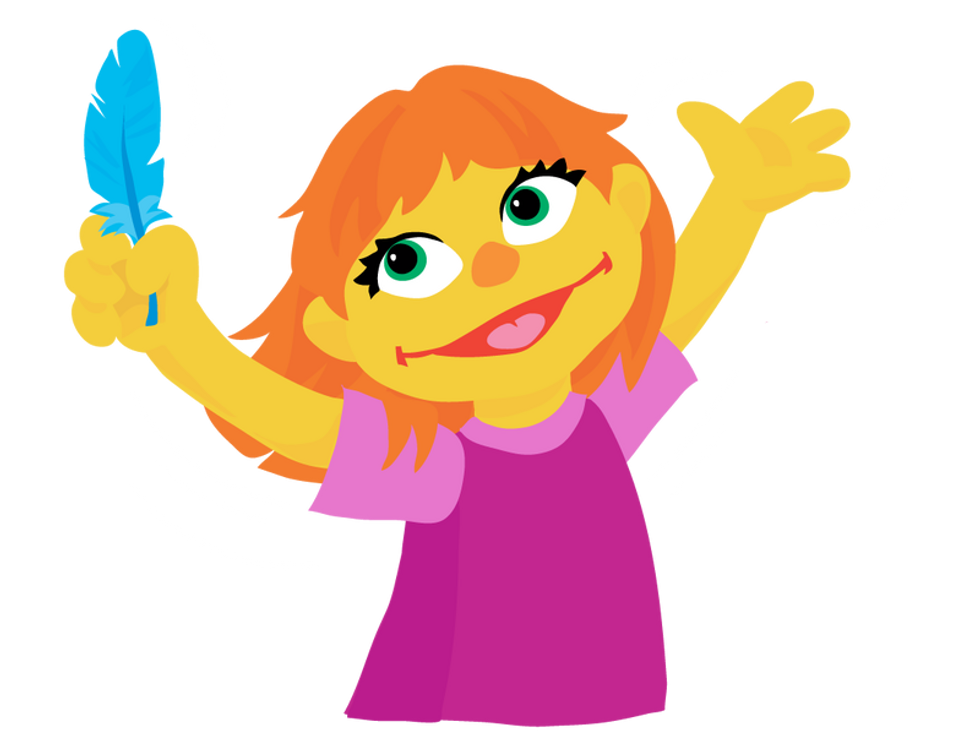

Meet Julia, the newest character to move to "Sesame Street." Over the past 50 years, "Sesame Street," a staple for children's educational television produced by the Public Broadcast Station (or PBS), has debuted dozens of new playmates for the likes of Elmo and Big Bird, but Julia is different: She has autism. Part of PBS’s new initiative to raise autism acceptance, Julia represents so much more than representation and her potential impact could change and shape lives.

Autism, for a general definition, is a developmental disability that presents itself differently in every autistic individual. But for example, some common traits or behaviors include heightened sensory experiences, difficulty interpreting social cues and using language, and narrow but deep interests in specific subject areas. In the past few decades, there has been a noticeable rise in diagnoses, resulting in the current statistic that 1 in 68 has been diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. But statistics don't mean anything after a certain point, especially when it comes to the autism spectrum.

While my days of watching "Sesame Street" are long behind me, I have to admit that I was absolutely elated to hear about Julia. I work with kids; in the school year, I help out in an after-school program for a private charter school and then in the summer, I work as a special needs counselor for a day camp. To me, Julia represents so much. First, she is the first autistic character on a children's TV show. But also, she's not just pushed into the background. She's used as a way to educate children to help them better understand what autism is.

Over the summer, I became really close to a boy that I'll call Paul. Paul was a second grader who thought he had the world figured out. We would sit together on the bus sometimes and talk, but he was the same age as my kids, most of whom were autistic. Paul found out halfway through the summer that my job was to work with kids with special needs and he just couldn't wrap his mind around that. He once asked me how my campers could be special needs "if they were so happy all of the time." From then on, his behavior around my campers changed dramatically. He spoke more slowly, and constantly looked to me for support whenever he interacted with one of them. But Paul wasn't doing this maliciously—he just didn't know exactly what to do.

I wish Paul could have seen Julia on "Sesame Street." Child psychologists and educators have always recognized the importance the show has on our children. The first study ever done on the show showed that children who watched the PBS classic from ages 2 to 5 had higher high school GPAs, more developed vocabularies and placed more value on achievement. The playful tone of the show and it's abilities to deal with different social issues—race and gender, for example—could have a similar effect on children when it comes to their social intelligence.

I think what's hard for children like Paul is that autism isn't something external. While some developmental disorders have physical traits, autism manifests itself purely in behaviors. How do you explain to a second grader why his autistic classmate acts the way he or she does? This is where Julia comes in. Now, instead of struggling to come up with an easy explanation, I can stop pretending that autism doesn't exist or that autism is too hard for kids to understand. They will have a point of reference and a gateway into understanding something that even adults need help understanding: That sometimes our friends are different and play differently and that's OK.

teenhorseforum

teenhorseforum