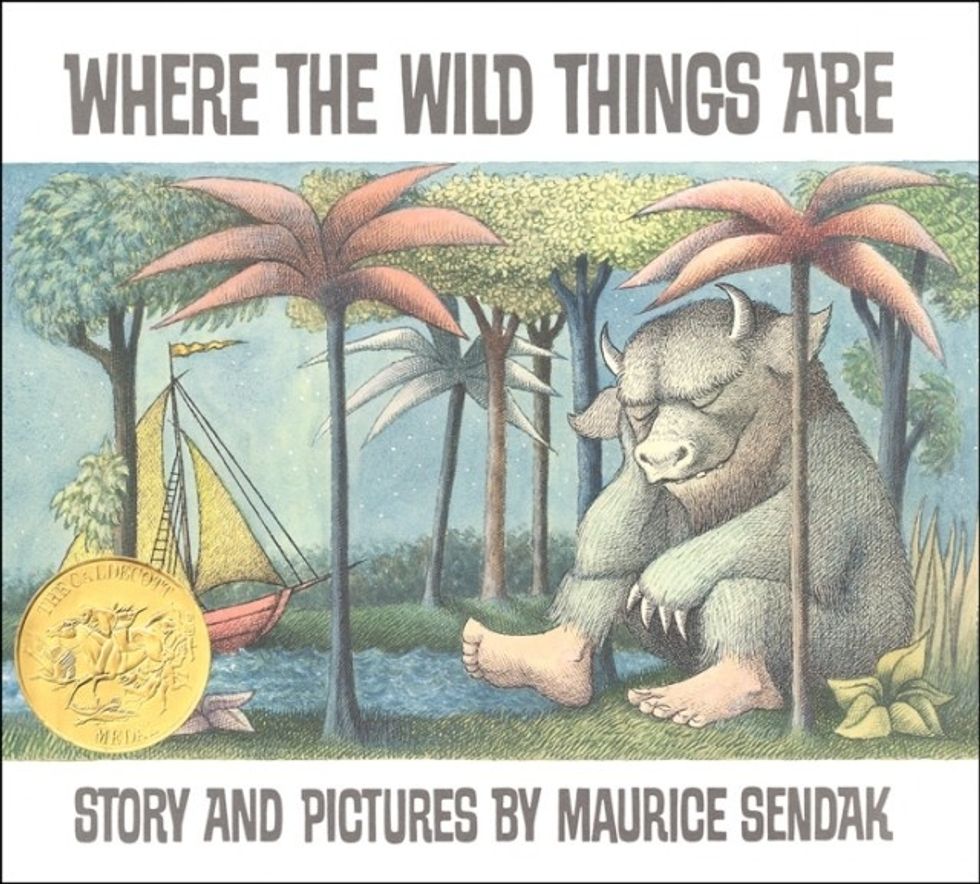

Today marks the seventh anniversary of children's author Maurice Sendak's death. Maurice Sendak is known for being the author of some of the world's most beloved children's books. These include titles such as "Where the Wild Things Are", "In The Night Kitchen", and "Outside Over There". Sendak, however, didn't consider himself a children's book author. He said "You cannot write for children. They're much too complicated. You can only write books that are of interest to them." When asked what children's books should contain, he replied, "How should I know?"

Sendak emphasized the idea that "childhood" as we know it doesn't exist. He believed childhood was a tough time, not only characterized by wonder and play but encountering issues that they don't yet have the skills to cope with or language to express. Sendak said that he "always had a deep respect for children" and how they "solve complex problems by themselves". When asked how they do so, he responded "I think through shrewdness, fantasy, and just plain strength. They want to survive." He went on to talk about Hansel and Gretel, and how Gretel had to save her brother's life. He said "Since when do children have to confront such terrible ordeals? Well, they do." Sendak himself had a difficult childhood, chronically ill, and coming from a family of poor Jewish immigrants. His parents, as he often said, were never meant to be parents, and he considered his older brother and sister to be his "good parents". Sendak, even as someone who dealt in the magic and mystery of childhood, never deluded himself about its reality. "Childhood is a very, very tricky business of surviving it," he said, "Because if one thing goes wrong or anything goes wrong, and usually something goes wrong, then you are compromised as a human being. You're going to trip over that for a good part of your life." Sendak talked about such experiences frequently, including a pivotal moment in his young life: seeing a photograph of the dead Lindbergh baby in 1932, released for only a limited time on paper before being removed the afternoon the news broke because Charles Lindbergh threatened to sue the press. Since then, Sendak became preoccupied with death. The realization, Sendak said, as a child that children die too, is something no adult wants to discuss. Adults, according to Sendak, do not want to admit that children, like them, face reality in all of its gruesome and discomfiting truth. When he brought up the Lindbergh baby to his parents, over and over they'd tell him "you didn't see that, stop saying that."

As he aged, Sendak spoke in nearly every interview about death, specifically the inevitability of his own. In a 2011 interview with Terry Gross, he spoke about it at length. "I have nothing but praise now, really, for my life," Sendak said, "I'm not unhappy. I cry a lot because I miss people. I cry a lot because they die and I can't stop them. They leave me, and I love them more." He followed with "Oh God, there are so many beautiful things in the world that I will leave when I die, but I'm ready, I'm ready, I'm ready." He was "a happy old man", but he'd "cry [his] way all the way to the grave."

He said to Gross, "Almost certainly I'll go before you go, so I won't have to miss you." He ended the interview after Gross said she wished him all good things, saying "I wish you all good things. Live your life, live your life, live your life."

Listening to Sendak speak, to me, is nearly transcendental. He had a frank and undiluted view of childhood, and a view of death that somehow encompassed a deep love for life, yet a welcoming acceptance of its end in due time. So often I feel a certain joy that knots itself deep in my chest and can only be untangled in moments of laughter, of unbridled happiness, of peaceful, silent moments spent with those in which those moments can occur and be valuable with. Sendak's love for people mirrors my own in such a way that every time I hear him speak about it, I can't help but tear up. Sendak held, with such genuine conviction, the belief that to be here, to see and smell and taste and simply experience life, was a religious experience. He felt "in conjunction with something [he] couldn't explain" when he experienced life in even the simplest ways, listening to music, or seeing an animal on a walk. He said it was "beyond his ego" as an "observer". I have felt that way for much of my life, and to see it put into words is a soothing, beautiful thing.

Sendak's honesty is a rare phenomenon. He doesn't rationalize, he doesn't delude himself, and he doesn't dull his ideas down for anyone. He was filled with love in a way that didn't include self-deception or ignoring the ugly side of things. Sendak saw life, and all its stages, as times encompassed by mystery, play, fear, joy, and every emotion one can feel. There are no age restrictions on what we feel. We are all simultaneously every age we've ever been. I'm a curious five year old afraid of the dark and I am a hearty nineteen year old determined to make a difference. All eras and sides of us exist simultaneously, just as Sendak always said. The meaning of life in Sendak's eyes is a malleable thing: simple, yet infinitely complex, and unable to be defined by only one person.

What can I, a nineteen-year-old girl, learn from an elderly Jewish man and his life's work? Well, as it turns out, everything.