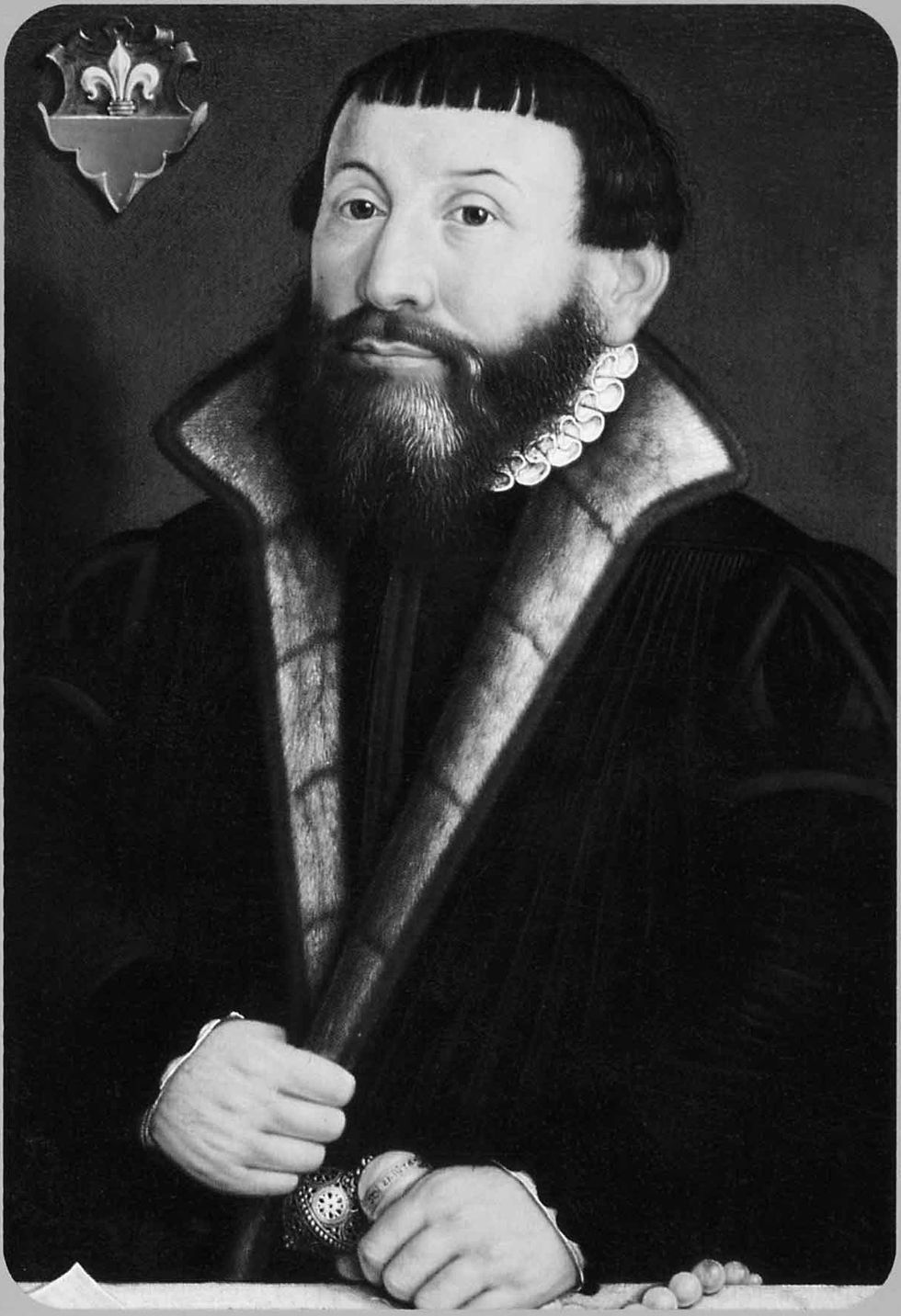

For a very long time in the Lutheran Church Missouri Synod, the name Martin Chemnitz was virtually unknown. Seemingly to always stand in the shadow of the greater Martin and Philip Melanchthon, his works relegated to the realm of specialist.

However, since Fred Kramer’s translation of Chemnitz’s Examination of the Council of Trent in 1971,[1] his name has been receiving more and more press: in fact, the launching of the volumes Chemnitz’s Works by Concordia Publishing House around 2007 has made his name more popular than ever.[2] Being a very particular and concise theologian, Chemnitz has become a symbol and standard of Orthodoxy in many conservative and confessional circles throughout the synod, and his works have had a tremendous impact on how we understand Post-Reformation Lutheran thought.

His work on Christology (The Two Natures in Christ) is the shining gem of Lutheran Patristic studies, amassing citation after citation of biblical and patristic data. And his contributions to the Solid Declaration of the Formula of Concord have made sure that his thought would continue to affect generations of Lutheran and non-Lutheran thinkers after him.

My overall plan with studying Chemnitz is simple: I want to understand how he is using the Church Fathers, so that we might uncover a sort of Lutheran “hermeneutic” for reading the patristic writers.

However, in order to someday reach this goal, I will need to review his biography, his major works, and, finally, some select passages specifically on the Early Church. This current paper is an attempt at part of the first item on our list—Chemnitz’s biography—utilizing the J.A.O. Preus’ The Second Martin.[3] I plan to outline, in this first paper, the events of Chemnitz’ life from his early days to the completion of his education.

Let us start in the beginning. On November 9th, 1522, Martin Chemnitz was born to Paul and Euphemia Chemnitz in a small Brandenburg town named Treuenbrietzen.[4] His father, Paul, was a cloth trader, and was successful enough that he could afford to give his son a decent education. This meant sending Martin away, from the years 1536-1538, to Wittenberg, so that he might have a good understanding of the basic subjects necessary for an education. Though he was not very outstanding at this point in his life, he did develop a particular love of the Latin language.

However, in the year 1538, tragedy struck. Paul Chemnitz died, leaving his family in financial hardship. The lot fell upon his two sons, Matthew (the elder) and Martin (the younger), to maintain the family business, so Martin was recalled from Wittenberg back to his hometown of Treuenbrietzen.

This was not to forever detain the young Martin, however. In 1539, he showed some of his Latin translations to two notable citizens of Magdeburg, and they did their best to convince his mother, Euphemia, to allow him to pursue studies at the University there. His mother consented, and Chemnitz left Treuenbrietzen a second time, this time for three years, gaining the opportunity to study not only Latin, but also dialectics, poetry, Greek, rhetorics, and astronomy.

Unfortunately, once again financial hardships fell upon the young scholar, and he was forced to leave Magdeburg. Thankfully, though, before he left, he was able to secure a job as a Greek tutor in Calbe an der Saale. The following year (1543), backed financially by his cousin Sabinus,[5] Chemnitz was able to finally finish his bachelors at Frankfurt an den Oder. During this time, he supported himself by teaching and a money clerk, as he added to his studies mathematics and the physical sciences.

In 1545, he decided to continue his education in Wittenberg, where Philip Melanchthon encouraged Chemnitz in his studies of mathematics and proposed he add astrology to his studies.[6] During this time, Chemnitz likewise had a chance to hear Martin Luther preach, although he admitted later that he did not give these sermons adequate attention. Ultimately, his studies at Wittenberg were interrupted in 1546 by the outbreak of the Schmalkald War.

In 1547, Chemnitz and his cousin Sabinus fled to Prussia. There, at the newly established university at Koenigsberg, Chemnitz attempted to resume his education- it was, however, interrupted again by the outbreak of the bubonic plague. Chemnitz and Sabinus proceeded to flee the city to a remote barn, where Chemnitz first began to study theology. There he read Luther’s Church Postils and Gabriel Biel’s Sentences.

Upon his return, Chemnitz was made the rector of Kneiphog School at Koenigsburg. At this time, he likewise was instructed by Philip to pursue the correct distinction between Law and Gospel, a teaching that would leave its mark on his professional work for the rest of his life, and gained access to the ducal theological library.[7]

On October 24th, 1550, Chemnitz’s life once again took a more dramatic turn: it was on this date that the primary Prussian theologian, Andreas Osiander, held his first debate over whether Christians were saved by forensic or inherent righteousness.[8] In his De Lege et Evangelio and De Justificatione, Osiander set forth the view, in opposition to both Luther and Calvin, that humanity was justified by a faith that was instilled in, rather than declared over, it.

This means that one would grow in faith over their lifetime, and eventually be saved.[9] Against Osiander, Melchor Isinder, Joachim Moerlin, and Martine Chemnitz insisted on the traditional reformation understanding of justification, that is, that it is a declaration of righteousness spoken by God over sinful humanity. The outcome did not favor the orthodox theologians, however: rather, Joachim Moerlin was expelled from Prussia and Martin Chemnitz, once forced to debate Osiander publicly, resigned from his positions of rector and librarian.[10] Despite two synods convened concerning the controversy, Osiander ultimately died that same year (1552), leaving the controversy eternally unresolved.

In April of 1553, Chemnitz returned once again to Wittenberg, boarding, by the arrangement of Sabinus, in the home of Philip Melanchthon. Here he was admitted to the Philosophy faculty, and, among his other duties (he was first tasked with examining potential graduate students), by the insistence of Melanchthon, Chemnitz began his famous lectures on Melanchthon’s Loci Communes: his Loci Theologici.

However, Chemnitz would not stay on the faculty for long: on September 28th, 1554, he accepted a call to the small Hansa town of Braunschweig, where he would spend the rest of his subsequent career. Joachim Moerlin, whom he had met nearly four years previously in Koenigsburg, Prussia, was the orchestrator behind the call; he was so impressed with Chemnitz’s orthodox stance during the Osiandrian Controversy that he wanted him to come to Braunschweig as his coadjutor.[11] Chemnitz was promptly ordained by Johannes Bugenhagen in November (without even a theological degree!)[12] and left for his ministerial and administrative work in the smaller city of Braunschweig. It is around this time that he (also by the orchestration of Moerlin) married Anna Jaeger, the daughter of Hermann Jaeger.

This is perhaps a decent place to pause in our biographical sketch of Martin Chemnitz. The council at Braunschweig went on to sponsor his doctoral work on Christology, which he completed in 1568, and with that the long and winding road of his education came to an end. With his call to the town of Braunschweig, a new chapter was dawning in his life and the life of the Evangelical Church: it was this chapter which would culminate in 1580, with the presentation of the newly bound and agreed upon Book of Concord to the Elector August of Saxony, the founding text of Lutheran Orthodoxy.

[1] Martin Chemnitz, Examination of the Council of Trent: Part 1 and Examination of the Council of Trent: Part 2, tran. Fred Kramer, (St. Louis: Concordia, 1971).

[2] Martin Chemnitz, Chemnitz’s Works, 9 volumes. Eds. Jacob Corzine and Matthew Carver. Trans. Jacob Corzine, Matthew Harrison, Fred Kramer, Luther Pellot, J.A.O. Preus, Andrew Smith, and Georg Williams. (St. Louis: Concordia, 2007-2015).

[3] J.A.O. Preus, The Second Martin, (St. Louis: Concordia, 2011). I will be supplementing Preus’ work with Fred Kramer’s biography in his Examination (pp. 17-24), Theodore Jungkuntz’s Formulators of Concord (Theodore Jungkuntz, Formulators of Concord: Four Architects of Lutheran Unity, (St. Louis: Concordia, 1977)), Robert Kolb’s entry in the Reformation Theologians: An Introduction to Theology in the Early Modern Period (Robert Kolb, “Martin Chemnitz,” in The Reformation Theologians: An Introduction to Theology In the Early Modern Period, ed. Carter Lindberg, (Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishers, 2002), pp. 140-155), and Aurthur L. Olsen’s biographical sketch, “Martin Chemnitz,” in The Doctrine of Man in the Writings of Martin Chemnitz and Johann Gerhard, eds. Herman A. Preus and Edmund Smits, trans. Marro Colacci, Lowell Sarte, J. A. O. Preus Jr., Otto Stahlke, and Bert H. Narveson, (St. Louis: Concordia, 2005), 223-229. Above all, the studies done by Jungkuntz and Kolb have been the most helpful additions to Preus’ research in the volume named above.

[4] Chemnitz, Examination¸ 17.

[5] Georg Sabinus (1508-1560) was a famous German diplomat, scholar, and poet during the reformation. For a short biography, see Otto zu Stolberg-Wernigerode’s Neue deutsche Biographie, vol. 22 (Berlin: Dunker & Humblot, 2005), 320.

[6] Though the modern theologian may be surprised to see Melanchthon recommending astrology, it was actually a very common area of study at the time, and should not be used to “prove” Melanchthon’s apparent unorthodoxy in his later career.

[7] These developments are critical to Chemnitz’s personal theology. Preus records that Melanchthon, in his reply to Chemnitz’s letter of inquiry into theology, responded by that “the chief light and best method in theological study is to observe the difference between the Law and Gospel” (Preus, The Second Martin, 92). Chemnitz was to apply this to his study of scripture and patristics back in Koenigsburg, as he systematically “read through the biblical books, comparing various versions, making notes on anything he thought memorable,” proceeding on to “the fathers, taking notes in the same way,” and, finally, he read “modern authors or contemporaries, especially polemical writings, of which there were many” (Ibid, 93).

[8] For an overview of the Osiandrian Controversy, see Ibid, 93-96 and Kolb, “Martin Chemnitz.”

[9] Some have speculated that Osiander’s soteriology was influenced by Eastern Orthodox models of theosis or christification. I personally am not too convinced this is the case, considering the fact that Neoplatonism influenced not only eastern but also Western medieval thought- however, I digress.

[10] This experience was to be the heat that would forge the lasting friendship between Chemnitz and Moerlin.

[11] That is, his “bishop’s assistant.”

[12] This perhaps shows how extensive his personal research was!

Energetic dance performance under the spotlight.

Energetic dance performance under the spotlight. Taylor Swift in a purple coat, captivating the crowd on stage.

Taylor Swift in a purple coat, captivating the crowd on stage. Taylor Swift shines on stage in a sparkling outfit and boots.

Taylor Swift shines on stage in a sparkling outfit and boots. Taylor Swift and Phoebe Bridgers sharing a joyful duet on stage.

Taylor Swift and Phoebe Bridgers sharing a joyful duet on stage.