Since the outbreak of fury caused by the Brock Turner decision last March, a national spotlight has been shining on the multiple cases of rape that have been popping up lately, focusing more specifically on how and why the culprits in question seem to be slipping through the legal system with little to no punishment for their actions.

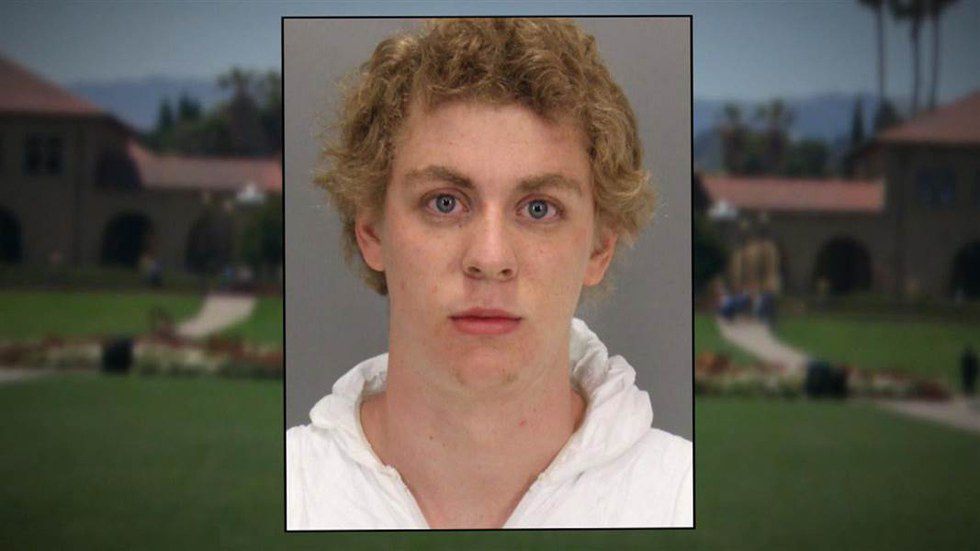

For those who don’t know, Ohio native Brock Turner is a former Stanford University student-athlete. The media incessantly reminds us that Turner was an honor-roll student, three-time All-American swimmer, and United States Olympic team prospect. Oh, and – I was so busy being impressed by his 200 yard backstroke time that I almost forgot- he’s a rapist.

Accused and convicted of sexually assaulting an unconscious woman behind a dumpster, Turner was given a whopping six-month sentence for his heinous crime. The judge presiding, also a former Stanford University athlete, assured us that, although the accusations against Turner were quite serious, his character witnesses were so sincere and moving that it seemed unnecessary to ruin his chances of a normal life over a ‘mere 20 minutes.’ In a letter to the judge regarding his son’s character, Turner’s father shared the devastating news that Turner had been so upset since the “incident” that he wouldn’t even eat his favorite meal, rib-eye steak, because that’s “just how good a kid he is.” In fact, Turner was apparently so polite and helpful while in prison that he was released three months early. Many were outraged by his early release a few weeks ago, but I believe our legal system is simply reminding us that the rewarding of good behavior is equally as important as the fitting punishment of bad behavior.

A s imilar case occurred here in Massachusetts last spring involving 18-year-old David Becker. A three-sport athlete at East Longmeadow High School, Becker “just got a little too drunk” at his friend’s party one night and, after being kind enough to stay and help clean up the house, beat up a younger boy and sexually assaulted two unconscious girls.

Fortunately for Becker, who was affectionately referred to by his friends as “David the Rapist” even before this party, the judge deemed his actions unworthy of a prison sentence and he instead received two years probation. Becker’s attorney was thrilled with the outcome, saying, “The goal of this sentence was not to impede this individual from graduating high school and to go onto the next step of his life, which is a college experience.” Because why on earth would we ever want to interfere with the future education of a rapist, right?

When it comes down to it, these are not isolated incidents; a pattern has emerged. It’s bad that there are people out there like Turner and Becker, but it’s worse that our society again and again attempts to absolve them from the blame for and consequences of their actions. These cases, and the many like them, have aroused fervent debate over gender and social equality, and for good reason. Some blame the increasing propagation of rape culture, a term used to refer to the ways in which society tends to blame the typically female victims of sexual assault and normalize male sexual violence. Others blame social bias, claiming that our society has a soft spot for young white males from well-to-do families, especially those who are athletes. I believe that throwing around blame will accomplish little, if anything.

It’s true that these cases cast a revealing light on our country’s lack of equality of all kinds, something our society claims to champion, but they also reveal our media’s tendency to misrepresent situations. I remember when the Turner case broke out almost every headline I came across was some variation of “Stanford University Student-Athlet Accused of Rape.” The articles would then go on to focus on safety at Stanford, Turner’s background, or even USA Swimming’s reaction to the whole mess. Even articles that tried to use the case as an example of our society’s problems fell just short of hitting the target because of one missing factor: the victims.

The discussion of lives being ruined over these cases always seemed to revolve around one life, the offender’s life, as Turner’s victim drew attention to in a letter she read to the jury and Turner himself. No one ever accounted for the second life that was ruined, her life. She said, “…you said that I want to show people that one night of drinking can ruin a life. A life, one life, yours, you forgot about mine. Let me rephrase for you: I want to show people that one night of drinking can ruin two lives. You and me. You are the cause, I am the effect. You have dragged me through this hell with you… If you think I was spared, came out unscathed, that today I ride off into sunset, while you suffer the greatest blow, you are mistaken.…Your damage was concrete; stripped of titles, degrees, enrollment. My damage was internal, unseen, I carry it with me. You took away my worth, my privacy, my energy, my time, my safety, my intimacy, my confidence, my own voice, until today.”

By utilizing these cases to make a statement about society, no matter what that statement might be, we become desensitized to the actual problem. These victims, they are real people, as are the culprits, no matter their skin color or athletic prowess. Until we as a society begin to realize and acknowledge that simple fact and act accordingly, we can forget about ever being able to solve the larger issues revealed by these terrible events.