Storytelling has been a tool used to navigate difficult situations for millenia. From oral histories passed on through song to our own middle school diaries, narrative structures have been used to reflect, learn, and remember significant moments in our own stories. One writer and publisher at Ember Publishing House, Sarina McCabe, often teaches others how to use narrative structures to make sense of their own stories. I spoke to Sarina, a current undergraduate at Emory University studying Creative Writing while on the pre-med track, about her take on innovation in trying times, mental health in the face of global uncertainty, and using narratives to make sense of the world around us.

Olivia Milloway: Hi Sarina, thanks so much for agreeing to talk with me today! First, I'd like to check in. How are you and your family doing in this moment?

Sarina McCabe: We're doing as well as can be expected! I'm back home in Indiana surrounded by lots of corn, but it's been nice to spend so much time with my siblings.

OM: Glad to hear it. How long have you been working with EPH, and what was the motivation behind founding the group?

SM: The idea actually started probably four years ago when I was really frustrated by the separation between the "humanities box" and the "math box" and the "science box". I felt like a lot of high school curriculum was very restrictive in that it kept each subject in its own vacuum and I really wanted to see how they were all interconnected. I ended up connecting with a team of people who were similarly interested in creating initiatives that would combine and explore the intersection between these disciplines. We wanted to bring out the strengths in all of those different fields in a way that supports both individual growth and learning but also community-level growth because we really need the expertise and the resources that all of the different disparate fields have access to.

It started off as a really small project, just a few friends that we're also interested in not being pigeonholed into individual disciplines. We eventually started thinking about how we could be a model to our younger peers on how they can expand their horizons beyond just one box. We started off with publishing some short stories and now we're moving into children's books and hopefully novellas and novels in the next few years.

OM: I understand you've been working on a new project with EPH on COVID-19 resources for children. Can you tell me a little bit about this project and what your motivations were?

SM: The project got started because my youngest sister, who's three, was having a really hard time understanding some of the changes to her daily life caused by coronavirus. She had a lot of questions about why she couldn't go to the park and do her usual activities and it was difficult to explain what was causing these changes to occur in a way that was developmentally appropriate. Because she loves to read so much, my brother and I, who's 16, had the idea to communicate some of these changes through characters that she could identify with in a story book. We thought it would help her process some of the more difficult questions and that story would act as a vehicle for understanding some more complex concepts. We created a little girl character that asked the same questions that my sister had and went about finding the support and answers she needed, but through play. Because my sister responded so well to this story, we realized that she wasn't the only kid that needed access to those resources and those mediums to explore some of their own questions.

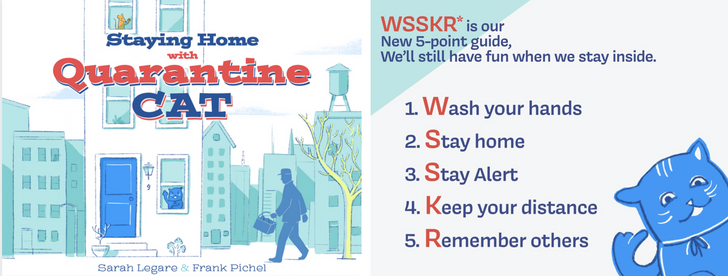

We started working with the publishing group to see if we could develop some more resources and involve professional writers and illustrators. With the publishing group's resources and know-how, we gathered together a group of people who are willing to work with us on those resources. As of right now, there'll be five books coming out this summer, utilizing a couple of different approaches. One book is making science more accessible and enjoyable to younger kids, which focuses on immunology and how our immune system keeps us safe. A lot of the other stories work to normalize what's happening in a way that kids can comprehend, like through giving cutesy acronyms to help remember handwashing and other preventative health measures. Another big aim is simply to help kids be able to emotionally process and cope with big transitions.

OM: You've given some workshops on writing as a means to work through personal troubles and trauma. I was wondering if you could discuss a little bit about why you came to value this process and why you think it's so effective?

SM: I'm saying this kind of anecdotally as a sort of pseudo-academic thought/fairly informed JSTOR opinion, but I think that people do grasp for that cohesiveness to string together their memories and their experiences to make sense of the emotions that we have. When we explain things to ourselves to understand past experiences or future aspirations, it typically takes the form of a type of narrative. And in many senses, I think that we view ourselves as the protagonists of our own story *cue the film score*. But in all seriousness, storytelling is a really important part of unraveling and unpacking our identities and seeing ourselves as the epicenter of the narrative that we're living. And I think that throughout our lives, we're constantly trying to find purpose and understand how and why things happen to us.

I think that journaling, or any kind of diary keeping, is also a form of storytelling. Most artists, photographers and painters and novelists would probably say that they infuse parts of themselves into their work. And I think that that's part of understanding yourself: putting your experiences into a medium that makes sense to yourself and to others, even if it's in a different way. Sometimes when you have thoughts swarming in your head and you're concerned about something or you're puzzling through a challenge or an issue that's bothering you, I think actually the act of removing it from your head onto the page makes it a lot less intimidating because it's like, "Oh, I can just look at this in words. I've turned these anxious thoughts and feelings into something that I can look at and physically have control over." So I think with a story, there is an element of control. In terms of my own life, storytelling and narratives are coping strategies. I definitely just speak for myself when I say that storytelling takes on the role that spirituality does in a sense, in terms of finding meaning in something and again, in understanding the interconnectedness of things and putting things into perspective. It's easier to feel hopeless in our actual lived experiences than when you're constructing a narrative.

OM: We talked previously about how storytelling can be a useful tool to make sense of the pandemic to young kids. How do you think people can use narratives to help themselves work through the pandemic?

SM: In the face of adversity, it's very helpful to be able to identify conflict resolution or lack of resolution in order to move forward. I think that identifying hope in whatever form that it presents itself is a very important part of how we navigate challenges. Again, because COVID is ever present and has been for the past few months, I think part of what is helping us to self-enforce some of those limitations that can be frustrating like not going grocery shopping when it's convenient, is the hope that things will be able to return to a more familiar state. And so there's kind of this idea where we're using what life used to be like, or the past, to inform what we can do in the present so we can have those experiences again in the future. And I think that's a very limited example, but there are plenty of times when past narratives and past experiences or ideas drive what's happening now. And in a much more physiological and concrete sense, I think the field of epigenetics is really looking into how past experiences can have a significant lasting impact on future generations and how they react to certain stimuli. But I know that that's a little bit more technical than we're talking about in our discussion about narratives.

OM: It's interesting that now we're living in a time where there's global uncertainty and civil unrest, resulting in collective trauma but also highly individual ones as well. If you could give advice to anyone living in our current moment, what would that be?

SM: If I had to give a generalized piece of advice, I think it would be to acknowledge and allow yourself to process your emotions because I think that in our fast-paced world it's easy to discount and bypass the full range of emotions that a sudden change can evoke. I think that even if we don't remember all the details of quarantine, the imprint of what happened will leave a lasting effect. Sit with your emotions. Let yourself fully feel them. Ask yourself simple questions. Take the time to check in with yourself. Some people might call that meditation. Maybe you just want to call it some time in the bubble bath in your own head. Ignoring those emotions and suppressing them and forcing yourself to just push through it or saying, "I am a happy person, I'm not allowed to feel sad or or disappointed or mad" or whatever can lead to emotional constipation, so to speak. And I think that, again, I kind of speak for myself, but I think that this is a widely shared experience among people who went through, especially like early childhood adversities, that the longer that you kind of prolong unpacking and working through some of that, the more painful it is to go back in and open up the scars and dig through everything.

Even though everyone is having difficulties brought on by the pandemic, I think that it's fair to say that it is not affecting all people equally. There are definitely communities, particularly communities of color and lower income communities that are being hit much harder than others. But, for a lot of people who weren't directly affected by the virus, it's really hard to even pinpoint exactly what was lost. If you don't have something tangible to grieve it can be really difficult to process and unpack loss. Regardless, it's important to help people understand that the emotions that they're having are valid and that it's okay to reach out for support.