Every woman has experienced it. You are looking for a seat on an overcrowded train, and just when you think you have found a seat, it turns out that a man is hunched down with his legs sprawled out, taking up four seats. Instead of asking him to move, you just keep looking for a seat. Or you simply decide to stand. Why is it that women commonly strive to take up less room, and be more adjustable, while men are able to use as much room as they please?

While the issue of space is not a gender specific issue, these photographs indicate that perhaps it is a problem that more commonly affects women. Centuries of male dominance has afforded men the opportunity to take up as much room as they please in order to feel comfortable. Perhaps they even feel entitled to that space. While this is obviously not ideal for female travelers, the greater problem is that they do not have the same opportunity; they feel as though they are not entitled to space to the same extent as men. Instead, women twist and contort their bodies to fit in small spaces as opposed to feeling comfortable. Perhaps this is because unconscious misogyny has forced women to become accustomed to both figuratively and literally utilizing the little space men have left for them as opposed to creating or demanding their own space.

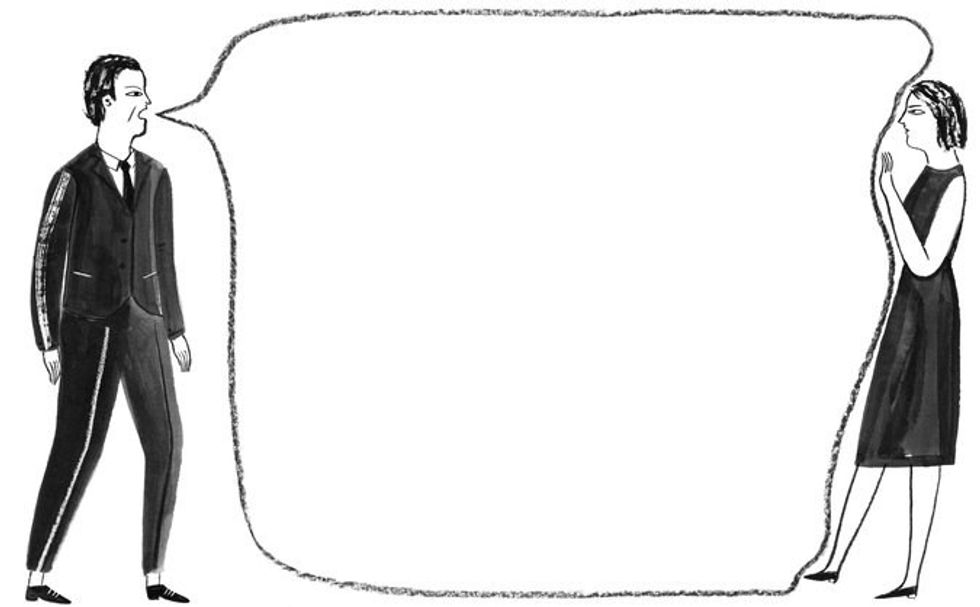

Not only have women physically shrunk themselves, but they have also intellectually shrunk themselves. NY Times article, “How to Explain Mansplaining,” by Julia Baird says that the space conundrum also applies to the male privilege of dominating conversation. Mansplaining is a more sophisticated way of saying that men often take up all of the oxygen in the room: “The prevalence of the monologue is deeply rooted in the fact that men take, and are allocated, more time to talk in almost every professional setting. Women self-censor, edit, apologize for speaking. Men expound.”

It is not uncommon for men to lead conversation as well as speak the most during that conversation. In fact, it is norm. It is not that women do not have much to contribute, but rather they do not want to interrupt in order to voice their opinions. In the minds of women during such conversations, their opinions seem lesser or secondary. While the author recognizes that some women can be equally long-winded, it is far less common for women to dominate conversation. Thus, the issue is that not only are men asserting dominance over space, but also time.

It is not the fault of men or women that these issues persist, but rather patriarchy that has accustomed people to be either dominant or submissive. However, it takes the work of both men and women to acknowledge their privilege and oppression, and adjust accordingly. Men can acknowledge their privilege by being aware of the space they take up and how much they speak during group conversations, and then do less of both. Women can demand the space that is rightfully theirs, speak more in conversation, and be unafraid to interrupt or voice their opinion. They can do whatever means necessary to be involved in the conversation, more so then they normally would. Small acts such as these will allow our society to work to establish gender equality. If men and women can occupy space equally as well as participate in conversation equally, perhaps greater change can come about as well. In taking these steps towards equality, we are collectively working to lessen the affects of patriarchy.

The minimum wage is not a living wage.

StableDiffusion

The minimum wage is not a living wage.

StableDiffusion

influential nations

StableDiffusion

influential nations

StableDiffusion