Last October when I was studying abroad in Berlin, Germany, my three friends and I decided to head down to Munich one weekend to take part in the Oktoberfest activities. Because Airbnb’s were too expensive and we didn’t want to have to miss school, we decided to only spend the day there, and take night buses. We left at midnight from Berlin the first night and arrived in Munich at about 8:00 in the morning. We walked up to the gates of Oktoberfest ready to spend the next fourteen hours enjoying the festivities and exploring the city.

A couple of hours into the day we were intoxicated and exhausted from the uncomfortable bus ride. I decided to sleep on the steps of a large statue but was promptly awakened by a large security guard who politely explained that I couldn’t sleep there. I proceeded to a nearby park and conked out, once again feeling safe in the presence of my companions. The four of us spent the rest of the day “homeless,” as we explored the town.

We snuck into hotel lobby bathrooms around the city, slept in multiple parks, and cherished the freedom we had to roam aimlessly around for hours. At about midnight, after returning to the Oktoberfest grounds for closing, we realized we still had hours to kill and nothing to do. With not much else left open, and no place to go home to, we reluctantly made our way to the bus station to wait for our 3:30 a.m. ride home. I remember feeling a sense of desolation mixed with fatigue. It dawned on me then just how privileged I was: I had the luxury of going home, my uneasy sense of aimlessness was a temporary state.

I then reflected on the day’s events with my privilege in mind. When the security guard came up to me, he could have easily fined or treated me disrespectfully. However, as a white, American, female college student, I was aptly catered to my appearance and status. No one questioned me and my friends when we walked into hotel lobbies to sneak trips to the restroom or fretted when the four of us passed out in a park sprawled across the grass. We could walk freely through the streets and interact with passerby strangers for directions or friendly conversation without hesitation from either party. Although I did feel stranded towards the end of the night, I hadn’t stopped to consider what it would actually be like to be without somewhere to end up at the end of the day. I wrongly equated homelessness with a sense of having free will.

The other day I was assisting my roommate with a project for her photography class. She was photographing the Boston Public Library, which is in the middle of the city. Many homeless line the streets around the building, some with signs and containers for money, others just hanging around. I take in their presence along the sidewalk as an accustomed part of my walk and treat them with no more consideration as I would a shadow of another passerby. I notice in this process that there is a separation between us, their isolation is blatant in a world who does not consider their existence to be worth recognition.

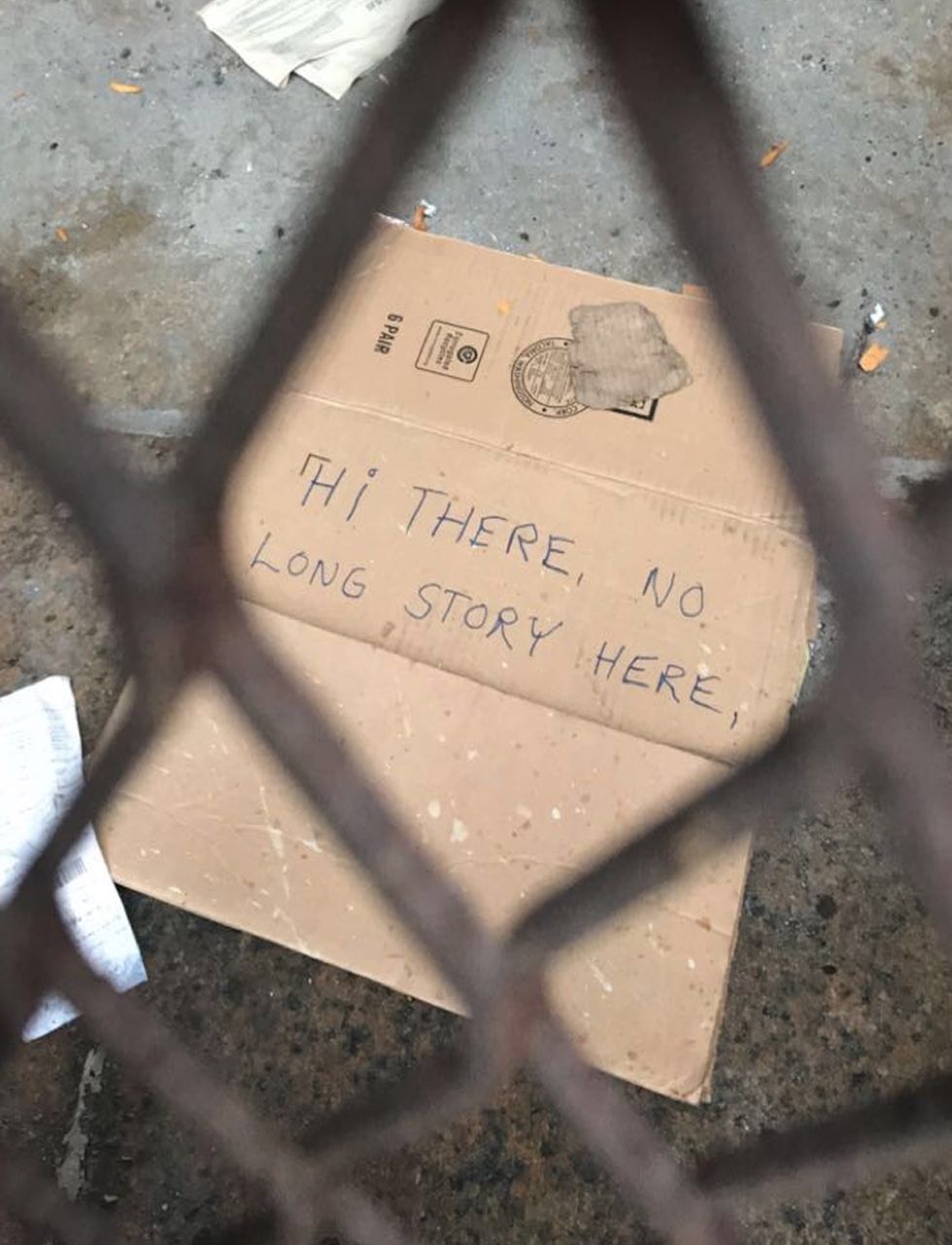

I stumbled upon a sign that re-humanized their homelessness. Behind a fenced section outside of the library, on the ground lay a soggy cardboard sign with text saying: “Hi there, no long story here.” I don’t know if this was an intentional play on words being on library property, or know who the person was who once held the sign, but it made me stop and think. We dehumanize the homeless to the point of not recognizing that they once were young, had a family, and a story. How did they end up where they are now; should that backstory even matter?

You see the signs they hold justifying their condition; written words conveying their status of an injured ex-veteran or an unemployed single mother and we pay sympathy to their predicament. But why should the reason for their homelessness justify their original self-worth or qualify the extent of their suffering? Many may not have “long stories” of how they came to where they are now, but that doesn’t make them less worthy of our acknowledgment or empathy.

We cannot classify their condition as a choice, as many of them have inescapable afflictions that prevent them from conforming to what we consider normalcy. Some argue that there are many services to get them back on their feet and their refusal means they are out of reach. However, we underestimate the effect that isolation and dehumanization have on a person’s mental health, and their ability to “help” themselves due to the disconnect between their world and ours.

Maybe there is no right way to deal with the homelessness on an institutional or even individual level, but I think ignoring them, or tossing a few coins there way every once and a while will do nothing to bridge the gap between our world and theirs.