Ever since our ancestors first looked up at the night sky, we have wondered whether or not we are alone in the universe. This yearning for discovery has significantly impacted humanity throughout our entire history, but never more so than now, when the once distant stars and planets seem so closely within our reach. Where have we been looking for life and, perhaps more importantly, why?

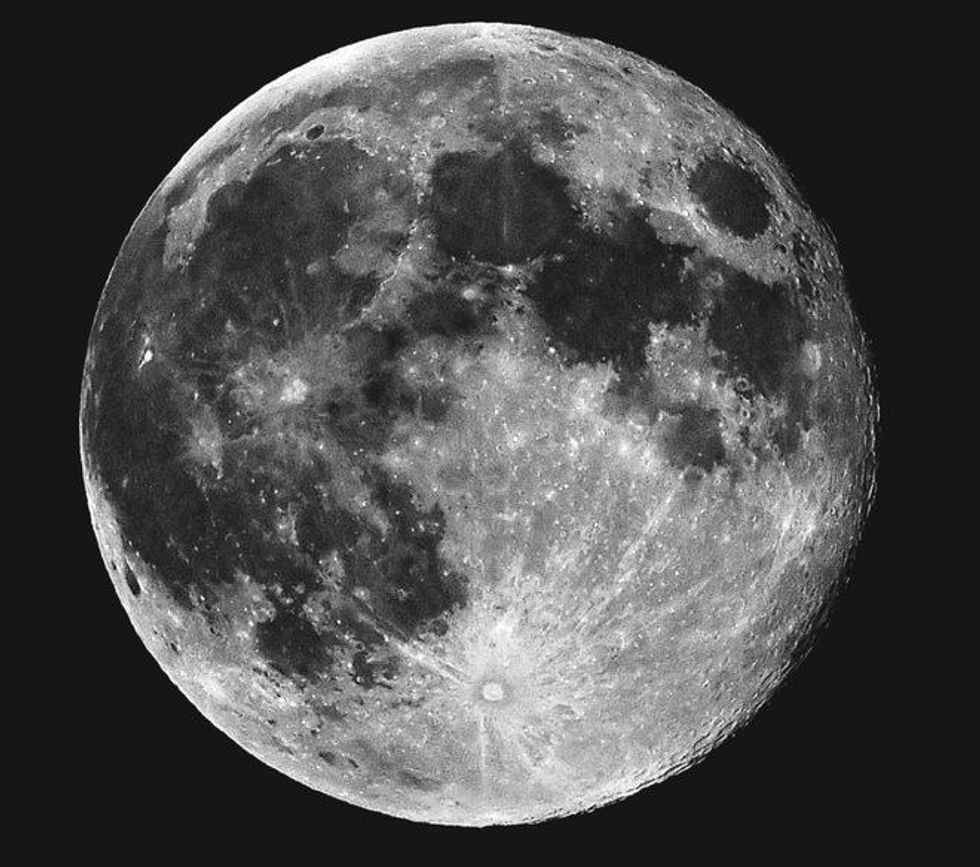

The ancient Greeks believed that the planets (or “wanderers”) were the physical aspects of certain gods, starting early astronomers down the path of assuming life in the heavens. When astronomers later developed the tools to more accurately study the planets, they began to fancifully imagine the conditions one might find on them. Geological features were named after that which seemed reasonable then, but now seems rather ridiculous (e.g. the large dark spots on the moon are called maria, which means “seas” in Latin, but they are actually large crater basins filled with lava that hardened into obsidian glass, and yet we persist in calling them seas).

A similar occurrence of geological confusion caused Giovanni Schiaparelli in the late 1800’s to note certain canale that he had seen on the surface of Mars. Canale meaning “gullies” but sometimes translated as “canals.” Percival Lowell took this information and ran with it, stating that Martian civilizations had created the canals to better distribute their dwindling water supply across their planet. This theory was considered credible for a few decades before valid points were raised about Mars’ atmosphere not having enough pressure for liquid water to exist. The Martian canal theory was finally put to rest when Mariner 4, a United States spacecraft, flew by Mars, giving us our first glimpse of the surface of another planet.

Though we didn’t find any canals or oceans, we did realize that other planets were finally within our reach, surely it wouldn’t be much longer before we were walking on an alien surface? Sadly, Mars’ temperature and gravity would not allow for easy colonization, and the whole venture will likely never come to pass due to the great expense and difficulty. However, even though Mars isn’t the best option for settling, it has opened us up to the possibility that there might be other worlds capable of providing humanity with a new cradle for existence.

Astronomers have identified several satellites of Jovian planets (gas giants, like Jupiter) that could have or sustain life. The three main factors that would denote the possible existence of organic life being present would be volcanism, a thick atmosphere, and water. Io and Europa, moons of Jupiter, have displayed some of these characteristics. Io has the most volcanic activity of any object in our solar system (caused by the tidal pull of Jupiter and several other moons), however, it is doubtful whether there is any life on this battered little moon. Europa has a thick crust of ice (believed to be 10 to 15 miles deep), and there may be a large world-spanning ocean locked beneath the frost, but if anything lives down there, it will be decades before we’d ever be able to get through the ice, let alone find anything swimming around.

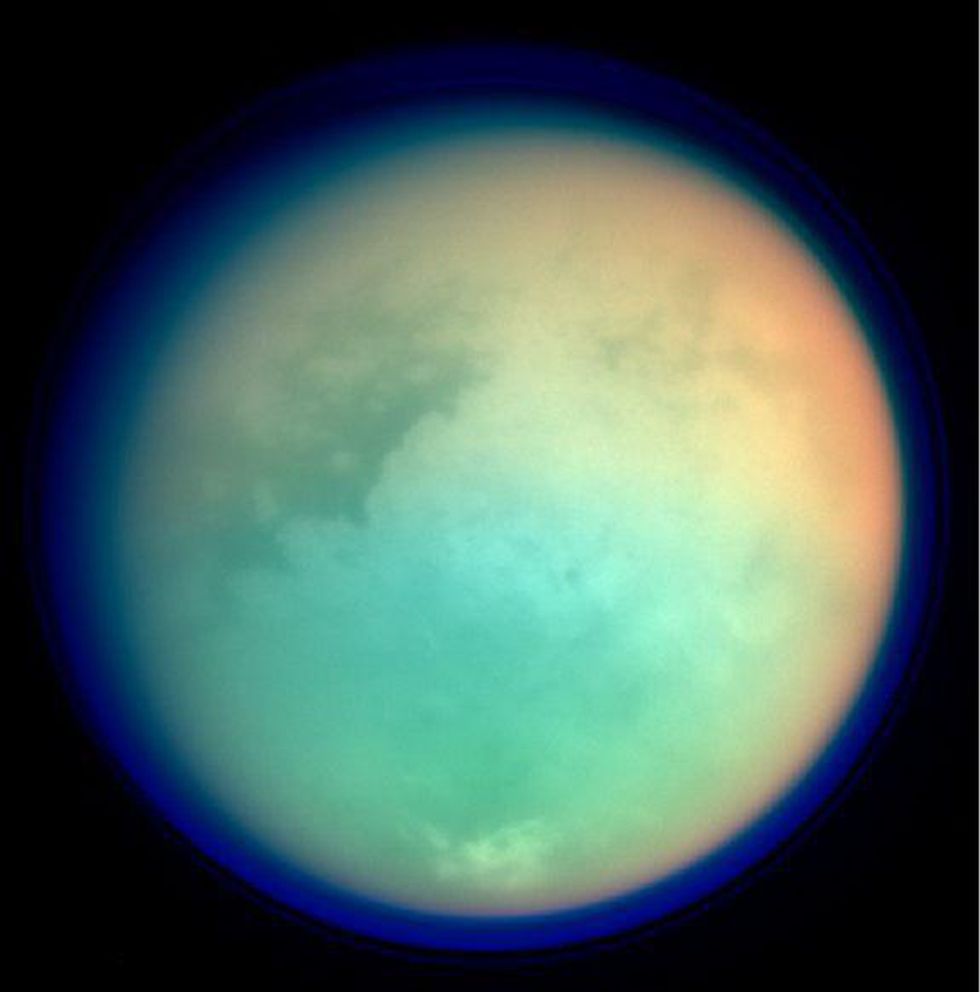

Saturn’s moon, Titan, is the best shot we have of finding life in our solar system. It has a thick atmosphere and obvious signs of liquid activity on the surface. Unfortunately, both atmosphere and liquid would be comprised of methane or ethane compounds. Titan is at the right distance from the sun for gas, liquid, and solid methane or ethane compounds to form (the same as Earth is at the right distance for H2O to occur in all three), so even though there may not be life on Titan, the fact that there are other places out in the galaxy where we could at least expect Earth-like conditions, is exciting.

Outside of our solar system, astronomers have been busy trying to discover exo-planets (planets with some of the signals making them capable of having life) in numerous ways, however, as always, it would be wise to question our tenacity in pursuing this subject. We have been trying to discover other sentient life for millennia, but why? What motivates our desire to find other people and places in the heavens? Would we benefit from contact, or would anything even change? As in any subject, proponents of astronomical exploration are fervent in their belief that we will be better-off because of their efforts, but I am unconvinced.

As thrilling as the idea of exploring different planets is, and as curious as extra-terrestrial life makes me, expediting our problems to another world will not make them go away. Before we can move on to that which is ahead of us, we need to deal with where we are now, and figure out how to live on Earth.