There’s no denying that the Americans with Disabilities Act has made a big difference in the lives of disabled people, including myself. For those who don’t know, the ADA, passed in 1990, prohibits discrimination against disabled people in employment, ensures equal opportunity in government services, and regulates the accessibility of public and commercial facilities, as well as in housing and transportation services. The law has made it more possible for those of us with physical or intellectual/cognitive disabilities to go to school, find work, and otherwise lead independent and productive lives. But, what was life like for Americans with disabilities before the passage of the ADA?

The Road to Freedom tour was a traveling exhibit in honor of the 25th anniversary of the ADA

At (relative) best, disabled people, including the deaf and blind, were marginalized or hidden away. At worst, people like us were subjected to inhuman treatment that made America look no better than Nazi Germany. Prior to the 1700s, people with mental illness were considered possessed by demons and if you had any kind of handicap, good luck finding shelter. You would’ve been kicked out of hospitals or shelters for the poor, forced to beg for money and food.

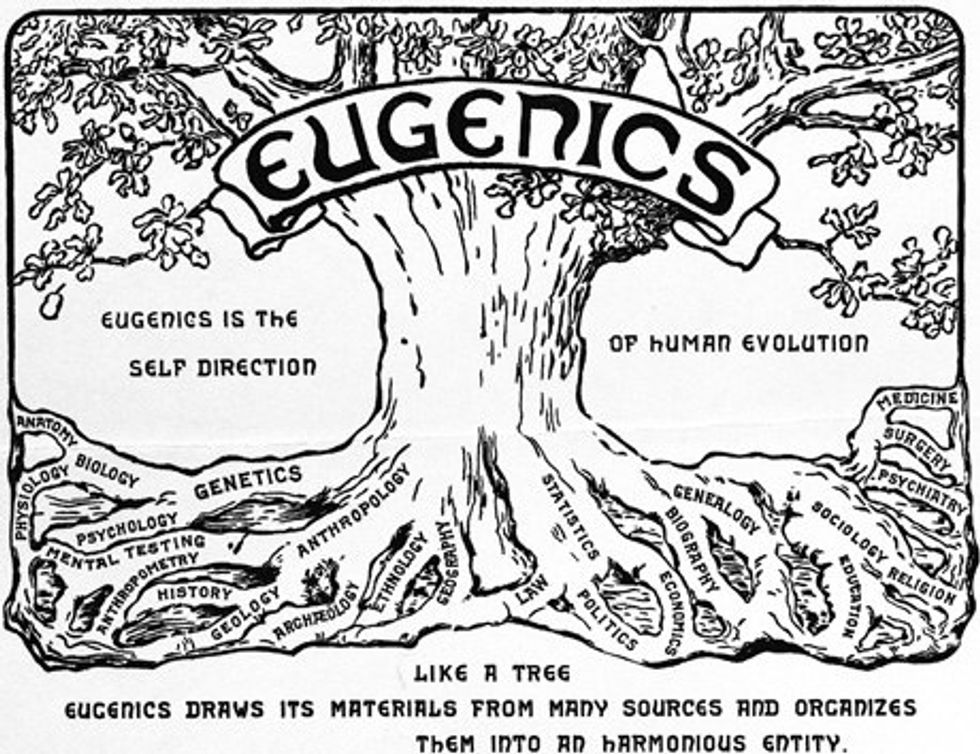

Things started to look up, at least for the deaf, when European “intellectuals” determined that deaf people could reason. Samuel Heinicke opened the very first school for the deaf in Germany in 1755. By 1800, the conventional wisdom was that disability came from genetic, rather than spiritual weakness. Unfortunately, the Racial Hygiene Movement also began to take hold, promoting an agenda to control reproduction and weed out the genetic traits they believed were weakening humanity. By the 1880s, this so-called science came to be known as eugenics and became widely accepted in America, years before it became a part of Nazi ideology.

The eugenicist agenda wasn’t limited to disabled people, but large numbers of the deaf, blind, and mentally handicapped were placed into segregated schools, or hidden away at home or institutionalized. This segregation, as well as the forced sterilization of people deemed physically and/or mentally “undesirable” or “defective” became law in 29 states, including Indiana and West Virginia. West Virginia became the last state to repeal its sterilization law in 2013. By the 1970s, nearly 60,000 people had been sterilized without their consent.

Eugenicist propaganda

On the brighter side, the 1960s and 70s saw a rise in disabled rights activism, drawing inspiration from the civil rights movement. During this time, a number of bills would serve as the precursor to the ADA, one of the most prominent being the Rehabilitation Act of 1972. President Nixon vetoed the 1972 act, but protesters continued to put pressure on the government and succeeded in lobbying for the passage of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. This new act prohibited discrimination against “otherwise qualified handicapped” citizens in federally funded programs and also called for sidewalks with curb cuts, handicap parking spaces, and ramps for public buildings and universities. Also of note is the 1975 Education for All Handicapped Children Act (renamed the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, or IDEA in 1990), which ended the practice of placing disabled children in segregated schools and allowed their parents to participate in the decision-making process.

Disabled rights activists push for access to public transportation in a 1985 demonstration

The ADA expanded the protections of the Rehabilitation Act into the private sector and contained more specific language. The law seems to have largely succeeded in ending discrimination against disabled Americans in employment, education, and public services, but just like with civil rights legislation, it hasn’t put an end to personal prejudices or negative stereotypes. Even so, it gives us a chance to prove ourselves as capable individuals, rather than burdens on society.