I have a serious problem with coffee.

It’s the first thing I think about when I wake up, and it’s the first thing I grab when I get to work (or get home from work, or sit down at a restaurant, or arrive at a friend’s house). To me, coffee is a priority.

And I know a lot about coffee… I know what I like and I know where to get it. I like my coffee:

Smokey…

Dark…

Intense…

And extra hot.

But am I addicted to caffeine? Is my coffee-drinking a symptom of dependency?

The word “addict” has entered our vocabulary to describe things or behaviors we really like or do habitually. We call ourselves “chocoholics,” “Sriracha addicts” and “caffeine dependent.” We assign our addictions to behaviors we find undesirable (but fun). I see this a lot on Pinterest.

And in this context, our addictions are childish, temporary, commonplace, inconsistent, manageable, and non-life threatening. “Addiction” is negative, unattractive, undesirable… but not serious. And true addiction- the disease of addiction- suffers as a result.

The word “addiction” has been simplified, redefined. By using it to describe our affinity for tater-tot pizza, we completely ignore all of the complexities of the disease.

This is obviously part of a larger issue. We’ve diluted a number of mental illness words over the years, including: bipolar, OCD, depressed, suicidal, and panic attack.

The problem with our lax use of “addiction” or “bipolar” is that it takes power away from folks who actually struggle with the disease. When I say, “I’m a candy addict! I can’t live without it, I eat it every day!” Where does that leave individuals who truly identify as addicts, who feel as though they truly cannot live without their substance, and whose use puts them in real danger every day?

Similarly, if I were to use “bipolar” to isolate or judge a single behavior (“I changed my mind, like, ten times… I’m so bipolar!”) I am further ostracizing individuals with these diagnoses and contributing to the misunderstanding of the disease.

When we describe our irregularities or oddities or desires or personality traits as an “illness,” it renders the word meaningless. We take the word away from those who actually own it

THE CASUAL ADDICTION

Our aim in using these words is to point to something wrong, negative, or irregular in someone’s behavior. This adds to the (already overwhelming) stigma attached to mental illness words. More specifically, using “addict” as an insult, joke, or slur reinforces the idea that addicts are:

Irresponsible,

Weak,

And dangerous.

And we forget about the medical and personal realities of the disease.

Let’s return to my coffee example. If I were to examine my use, here’s what I'd find:

- I drink coffee when: I’m feeling tired, overstimulated, or awkward (What precipitates the event?)

- I drink coffee to: establish a routine, ground myself in my environment, feel motivated (What “patterns of use” exist?)

- The last time I went without: I was on vacation and didn’t feel pressured to perform, or out of place. I sub coffee for hot water on days I feel sick (How did you accomplish this?)

It turns out that my coffee-drinking is tied to a number of behaviors, many of which are anxiety-quellers and promote comfort/competency. But am I addicted to coffee? No. Do I rely on the routine of coffee-making to reach a desired feeling state? Maybe. But I’m not “caffeine dependent.” Coffee just serves as, what psychologists call, a “transitional object” (or security blanket).

Although it may feel as though I’m “addicted to drinking coffee,” using that type of language simplifies the term “addict” and ignores the experiences of true addicts. Make sense?

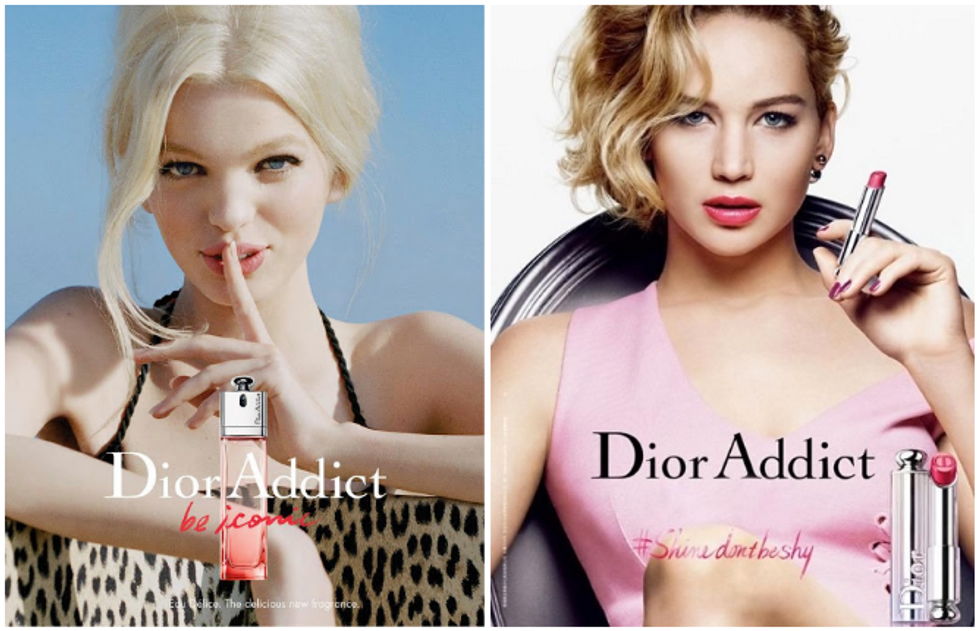

Advertising fuels our bad habits around language, and it presents coflicting messages about addiction in particular. One message is that addiction is positive: A product’s addictive qualities somehow proves its value. True addicted folks may wonder, why is “addictive” an alluring characteristic? Do we really want to be addicted to a particular brand of potato chips?

Just as someone processing a break-up is not necessarily majorly depressed (although- and this is important to note- life stressors can prompt the onset of a mental illness), eating pizza three times a week does not a pizza addict make.

WORD PLAY

So where do we draw the line? Pop psychology tells us we’re addicted to our phones, addicted to our relationships, addicted to buying clothes online. But are these true addictions? Or are we changing the way we view and describe “addicted” individuals and “addictive” behaviors? And if this is the case, where does it leave “traditionally addicted” folks? (I’m struggling to find the terminology here… which is illustrating my point.)

In fact, many clinicians are paying closer attention their choices around language and illness. In some cases, referring to someone as an “addict” (or “by their diagnosis”) may feel faux-pa, inappropriate, and dehumanizing. Perhaps the landscape is changing.

RESPONSIBILITY & LANGUAGE

And although it may sound like I’m splitting hairs here, I believe language is important. I’ve always advocated for careful and deliberate speech, especially around gender and sexuality. Just as I choose not to use the word “girlfriend,” (I prefer gender-neutral “partner”) and notice a lot of misunderstanding around the term “feminist” (tone akin to “femi-nazi”), I am in full support of reconsidering the ways I speak to and about my clients, and reexamine any inadvertent labeling therein.

But maybe this is all political, millennial jargon… “folks are offended by everything these days!” Or maybe not. The next time you describe your discomfort as “anxiety” or crappy day as “depression,” ask a friend or family member with anxiety or depression how this makes them feel. Just opening the space for dialogue is important.