"Bad"

A recurring image throughout the two-part documentary "Leaving Neverland" is the apparent childishness of Michael Jackson. He was gentle, silly, prone to giggling, and altogether removed from the larger-than-life image generated by his peaking stardom in the '80s and '90s. But underlying this outward immaturity wasn't the same naivety and innocence of the now-grown children whom he "befriended" during his renowned career. In fact, two of his accusers, visibly struggling to recall on camera their experiences with the pop idol, present Jackson as a man keenly aware of the outrageousness of his actions, a man strategically working to seclude these star-struck boys from their families in order to perpetuate his relationships with them and protect himself from damning inquiry. This is the inherent dichotomy of the "creative genius" that both endeared him to his young fans and enabled the hidden trauma that is only posthumously receiving serious attention over a decade and a half after his second battle against charges of child molestation.

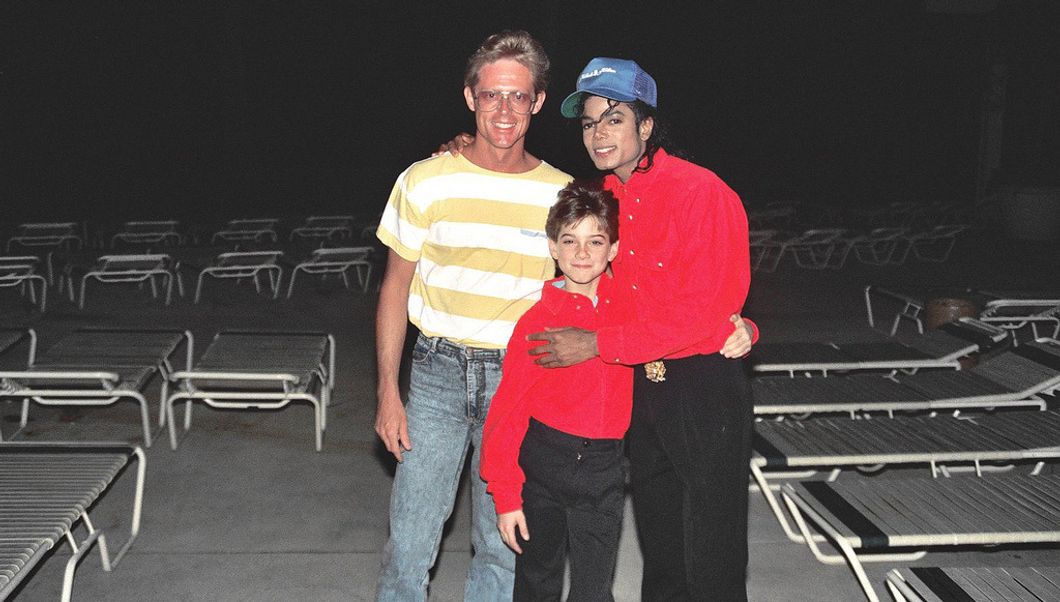

While some still steadfastly adhere to claims of Jackson's innocence, it's nigh impossible to dismiss the vividly horrifying episodes recounted by Wade Robson and James Safechuck through anxious grimaces and trembling voices. Yes, they protected their hero in previous testimony. Yes, they allowed their "comrade[s]" in abuse to suffer condemnations of self-seeking slander. Yes, according to their adult recollections, they lied. But to believe that Jackson's involvement with these boys, with Jordan Chandler, with McCauley Culkin, Brett Barnes, Gavin Arizo, and the unnamed others was nothing more than boyish friendship is a dangerous testament to the cognitive dissonance that underscores our collective difficulty in accepting imperfect idols. Yet assuming that Robson and Safechuck are telling the truth, which, given the poignancy of their accusations and the fact that extortion from the late Jackson has been removed from the motive equation, is a reasonable position, we have to ask: how did this happen?

Clearly, something prevented Jackson from transitioning from famous child to adjusted adult. Most likely this was a symptom of his early stardom, a sort of social pathology that denied him the opportunity to live a casual life. He didn't endure the trial and error of regular adolescence that, through socialization and adversity, eases us into the deeper realities of adulthood. Instead, he was stunted, peerless, overridden by the loneliness born of his extraordinary circumstances, and never able to develop beyond the mentality of an isolated youth. Yet he was a grown man with a grown ideology. He was cynical, secretive, and jaded in a way that belied the simple kindness with which he was frequently described. As his accusers and their families remember, he was loving, generous, easily accepted. Thus, while I can't say his predatory proclivities were the end-all-be-all of his personality, I think it's a safe assertion that they were his least public and most unconscionable characteristics. Yet this was the very façade below which his morality crumbled. It was the deception through which he understood himself as a friend, as a father, and most absurdly horrific, as a lover to boys as young as 7 years old. Whether he truly believed these delusions or not, there's no doubt, Michael Jackson deeply and negatively affected the emotional lives of the children who accuse him of systematic abuse.

"Dangerous"

What allowed his continued manipulation? What prevented Safechuck and Robson's mothers from embracing the visceral strangeness of their sons sharing a bed with a thirty-something-year-old man? An interplay of several factors both enabled and sustained these unquestioned, unaudited relationships for years at a time. First and foremost was the victimhood embraced by Jackson himself. The aforementioned dichotomy of a superstar outcast engendered sympathy from both mothers, kindling in them the idea that it was acceptable for a mega-famous adult to become so unnecessarily close to young kids. They recognized his lack of a childhood. They understood his desire for companionship and, in the case of the Safechucks, they found his love for their average family life beyond charming, even pitiable. James's mother saw him as an adopted son. She relished the idea of such an important person taking interest in their averageness and easily accepted Jackson's repeated visits, his long phone calls with her son, and their nighttime walks around the neighborhood.

Yet these concessions were founded directly upon Jackson's fame. Indeed, the professional and material aspects of the boy's relationships with the pop star were significant forces behind their families' acquiescence. This wholly unequal power relationship was the second key factor that deepened Jackson's access to the boys. Any interaction with the star led to stage appearances, interviews, commercial success, and the taste of a life previously unimaginable. How can you deny anything to a man of such supremacy? It was this combination of his outward insecurities and his unmatched influence that blinded the victims' families to the extent that their own personal discomforts were obscured. The Safechucks enjoyed their first-class flights, their limousine rides, and their grand rooms at the finest hotels, falling in line when the room shared by James and Jackson moved farther and farther away from their own accommodations. When you're invited on a world tour, how can you quibble about sleeping arrangements? The Robsons, after receiving an invitation to Jackson's estate following his appraisal of Wade's dance tapes, were wined and dined to a point of such contentment that they allowed their young son to stay with Jackson, alone, for a week's time. Why not, when his dancing could be honed by such an outstanding teacher? Clearly, in both instances, material comfort overrode inhibition, and unassuming star-power eroded reason.

The third and perhaps most foundational factor contributing to Jackson's pattern of abuse was the depth of intimacy he developed with the boys, which can only be understood through both his façade of innocence and his severing of familial oversight. His physical relationship with Safechuck began when they toured together in 1988, but for over a year Jackson had groomed both the boy and his family through gifts, vacations, and continued close access that fomented a sense of unrivaled attachment between them. For Robson, the abuse began with the trip to Neverland. Jackson drove Wade and his sister to the estate, playing them unreleased tapes which both fueled their excitement of the encounter and again founded a closeness that others couldn't attain with the idol. He preyed on this intentionally, utilizing the automatic bond between fan and celebrity to draw the kids closer to him at the expense of their family. In both cases detailed by the documentary, Jackson used phone calls, nicknames, and letters to deepen his ties to the boys. He slowly but surely introduced them to sexual activity, normalizing their physical encounters and their increasing emotional, sometimes literal seclusion from anyone else. And it wasn't difficult. Besides the fact that he was who he was, they were too young to possess the skills necessary to discern true friendship from manipulation. Jackson was like them. He loved popcorn, candy, and movies. He used childish parlance in both conversation and correspondence. He easily convinced them that he was their advocate, that he was a replacement for their parents, that he deserved the same love he bestowed upon them.

Thus, stardom, support, and solidarity were the main reasons why neither Robson nor Safechuck recognized the abuse for what it was. Even when accusations came to light, they were so manipulated by the superstar that they feared the consequences of cooperating with prosecutors. In fact, he'd told both victims that if their relationships were ever discovered the repercussions would be beyond severe for both parties. But their repeated defenses of Jackson were not entirely born of this fear. Both men acknowledged that they wanted to help him. They fully believed that he was their friend, and they wanted to regain the closeness Jackson had once exclusively offered to them but had diverted to other boys over time. So, when a mixture of anxiety, fear, and duty demanded that they lie to their parents and investigators about the details of their relationships with Jackson, the only alternative was to defend their friend. And in the end, their loyalty was rewarded with renewed attention. The boys derived excitement and even a sense of normalcy from his invitations to visit following both trials. Physical intimacy with Michael Jackson wasn't an aberration, it was a comforting return to life when they were the focus of his misappropriated intimacy.

"HIStory"

One of the main criticisms against "Leaving Neverland" is that it fails to include a defense from the Jackson family. There isn't another point of view to consider and corroboration for the accusers' stories comes from relatives, who aren't exactly unbiased. Yet we've already heard Jackson's defense, twice in front of cameras in a court of law, and as a result, public record is the key claim to his innocence. Thus, by offering a pulpit to undercut the claims made by Robson and Safechuck, the documentary would simply be a repeat of the battles we've seen played out before and would do little to foment the discussions engendered by the film's release. In my opinion, a side-by-side comparison of accusation and explanation would actually benefit the former as any rational justification for the claims made by these men would seem disingenuous and frail. But I digress. Rather than a rehashing of previously settled matters, the documentary instead offers a platform through which the full scope of Jackson's abuse scandals can be assessed. It's a more dignified approach in telling the stories presented and, although it may tilt audiences more toward the side of the accusers, it's time to hear allegations that don't come from terrified children on a witness stand. Let the Jackson family respond as they will. The fact is that they still possess the benefit of the doubt, while Robson and Safechuck continue to face scrutiny and scorn for their courage in recanting the past and sharing what they know as fact.

"Invincible"

So where do we stand now? Obviously, this documentary is not a conviction. It's not an adjudication of guilt and it by no means definitively proves the accusations that have followed Jackson since his death a decade ago. But it's an intense recounting of personal trauma that, through the similarities in both theme and detail given by Robson and Safechuck, is impossible to ignore. To be sure, we're living in a different climate than 2005, and we're far removed from the first trial of 1993. Our society's discussion of sexual harassment has improved, victims are not immediately dismissed, and we've progressed in our ability to hold the powerful accountable for their actions. As we've seen with Harvey Weinstein and Bill Cosby, as charges mount, and people expose their wrongdoing, our opinions turn, investigations open, and legacies die. Yet there's something different about Michael Jackson. Boys came forward, investigations were opened, and details surfaced that you'd think would leave lingering doubts in the public's conscious. Jackson admitted to sleeping with the boys. But clothes were on, he'd say. He was like the kids, the families would contend. They were just playing, enjoying innocent companionship. He was acquitted, after all, and the number of accusers wasn't nearly as overwhelming as those more recent examples. But how many does it take?

Throughout each bout of litigation, Jackson's supporters swarmed courthouses to maintain their support. The accusations were extraordinary, but it was impossible to think that such a peaceful, gentle man could be guilty of what was claimed. His accusers were, and are, different from those to whom we've sadly grown accustomed. You'd think that children would engender greater sympathy and less public reproach, but the impenetrable stardom of Jackson painted a target on the backs of anyone, of any age, who would try to dethrone the king of pop. And indeed, the testimonies by Safechuck, Culkin, and Robson fueled the doubt. Men like Weinstein and Cosby are without such convincing witnesses. Yet it wasn't considered that these boys were sheltering themselves and their families, that they had fallen victim to Jackson both physically and mentally so that any betrayal of his confidence was unthinkable. Pragmatically, such a proposition was not a sound discrediting device for the prosecution. Such suppression of fact is unprovable. The boys were bound by law to tell the truth, whatever weight that holds for adolescents suffering such a moral dilemma. In effect, their youth was an asset. And thus, with acquittal, came relaxed oversight. Safechuck and Robson recollect that Jackson immediately reverted back to his tried-and-true tactics after each exoneration. His celebrity remained intact, he lost but an ounce of the public support he wielded so readily, and it seems that he was freer than ever to pursue his predilections as our already biased dispositions toward the famous were buoyed by legal backing.

With Robson and Safechuck's 2013 lawsuit thrown out according to a statute of limitations, public truth has been set in stone. Michael Jackson, in the eyes of the law, was not a child molester. But we have to ask ourselves, with monetary compensation unavailable, why did these men agree to be interviewed for "Leaving Neverland"? Why bear their painful past to the world despite the firestorm of incredulity they knew they'd receive? This is the point of the documentary. We, as viewers, as fans, as rational adults must decide for ourselves what we believe. Are they lying? Have they deceived not only us but also their parents, their siblings, their wives? I'm reminded of the debacle that was Brett Kavanaugh's approval hearings in which Dr. Christine Blasey Ford nervously related her encounter with our newest supreme court justice. She stood to gain nothing from her public account, yet she braved the exposure to tell her truth despite the consequences. In that case and Jackson's, the onus is on us to make up our minds as no further investigation will be conducted.

While I'm by no means a diehard Michael Jackson fan, I recognize his talent and enjoy his music. I was too young to witness his legal battles, but I've always been aware of the accusations that circle his legacy. I've always dismissed them as speculation, as unproven rumor, and were I old enough, I probably would have accepted his acquittal as truth. How could I not? We're all only as secure as our courts are just. But new evidence demands new skepticism, and I now have a different perspective on both his person and his success. I can't help but look at every album cover and think of the troubled men who understand him, in the words of James Safechuck, as an "evil man." Can we no longer enjoy his work? Can those who grew up with his music no longer appreciate the memories that accompany it? For deniers, these questions are meaningless. But while his accusers and their families acknowledge the scale of his talent and the breadth of his influence, I'm sure they're no longer dancing to "Smooth Criminal." Maybe we can separate the man from the music, the icon from the indictments, but it's for each of us to determine. What's certain is that we can no longer blind ourselves with idolatry. Our heroes are human, and they can err beyond what we can imagine.