A few years ago, I went to listen to a Holocaust survivor tell her story. Hearing her memories transformed history into living letters of flesh, blood and emotion rather than mere reports of days gone by. As I left the event, I realized that my children would most likely never experience what I just had. They would never watch a spunky white-haired woman blink back tears as she remembered her days in a Nazi prison camp.

One day, no one will know what it was like to watch the Twin Towers fall on 9/11, just as I don’t know what it was like to reach the end of World War I or World War II, or hear that the Titanic had sunk. Our grandparents survived much more than World War II, but I know I have grossly neglected asking about what they can remember of what I can only imagine.

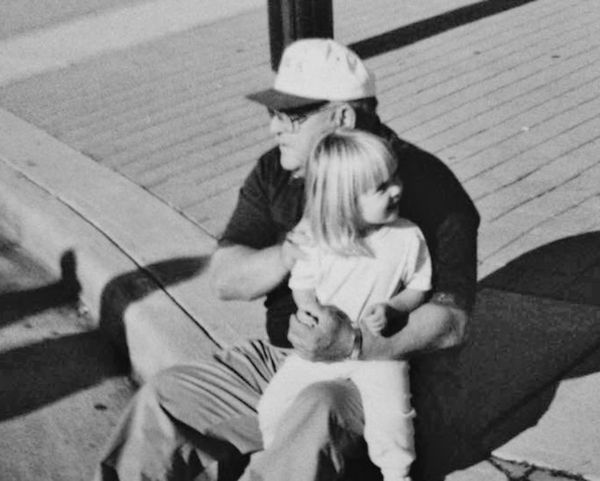

Our elders have seen much more of the world than we have. They remember the events that we cannot. They remember using typewriters instead of computers. They have lived through a world we will never know, and they have already accomplished the things we hope for or fear: leaving home, finding a job, starting a family, and losing loved ones. Reliving their memories with them is important because it gives us a firsthand account of unfamiliar events and a taste of the culture of the time. Also, no matter how long ago they were our age, they lived through all the confusion, excitement and anxiety of figuring out life and have advice on how we can do the same.

There is one more reason I believe it is important for our generation to pursue the stories of the past. We constantly seek to question or even tear down the ideologies of the past. Learning why older generations believe what they do can help us disagree, agree or understand. I have often heard people complain that their grandparents are bigoted, critical or narrow-minded. I am not saying the attitudes of the past are always correct. However, we should remember that our grandparents did not merely wake up with these opinions nor were they born with them. They have their opinions and beliefs for a reason, and that reason is often based on the experience of twice as many years as we have been alive. They may be right. They may be wrong, but I do not think we can dismiss them until we understand them. While I do believe it is important to test the traditions handed down to us, we should do so respectfully and never dismissively.

I would encourage you to talk to a grandparent, a neighbor, a professor, a church member, or anyone else who remembers what it was like to be young before you were born. Then ask them for a recipe. Ask about their parents. Ask about their childhood. Ask how they spent their time. Ask about the time your grandpa’s family took in British children during the London blitz, or about when your grandma worked in an ice cream parlor making ice cream sodas, or about your grandpa's experiences growing up on the family farm. Learn the stories your children will not have the opportunity to hear firsthand.

Memories of the past, even if they are not from relatives, give us a better understanding of their past and our present, and they teach us more about the world, stealing us for our future.