As a privileged white female growing up in the state of California, I had no reason to fear going to jail. And yet, from the instant I found out incarceration was a common form of punishment, I was completely terrified at the notion that I, too, would one day be locked up.

I would live out my days in an orange jumpsuit and get periodic phone calls with mom and dad and the loved ones that had been stripped from my life.

To this day, I’m a law-abiding citizen. I hate risk and I’ve seen too many “The Faces of Meth” articles to even touch a drug harder than Tylenol. I cried as I was being written my first speeding ticket at 18.

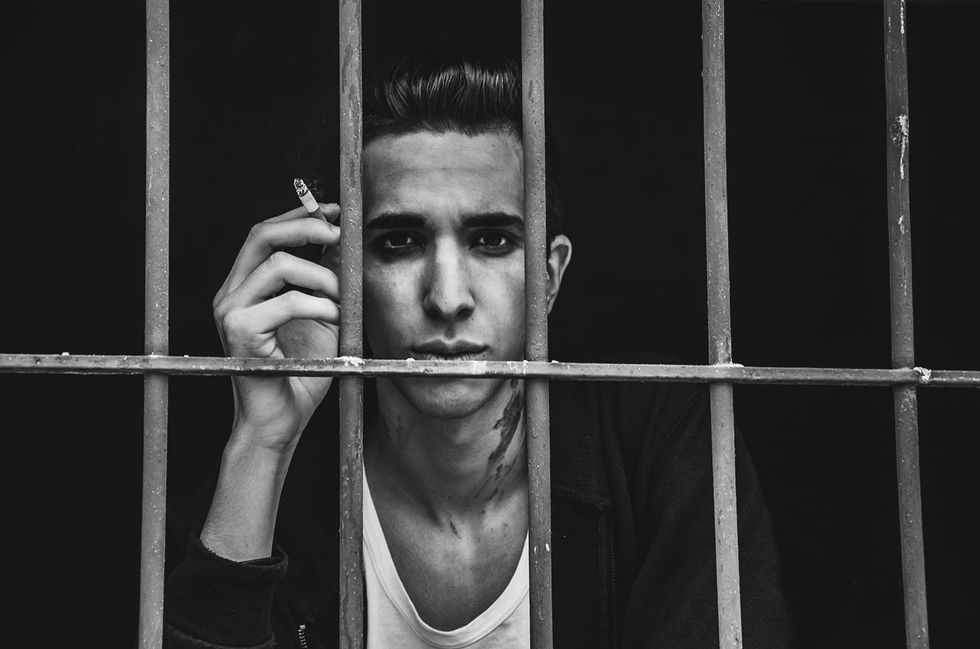

For some, incarceration is an all-too-familiar story. Cops patrol the streets, break down doors, arrest individuals in their own homes. It is in these neighborhoods that a simple game of “Cops & Robbers” is colored with detail. “I have a warrant for your arrest,” a six-year-old shouts as he pushes his friend up against the house and binds his hands in imaginary cuffs. Five years later, that same kid would face his first criminal charges for being driven to school in a stolen car.

Alice Goffman, author of “On the Run,” delivered a chilling TED Talk recounting her fieldwork in a struggling Philadelphia town where older brothers taught their siblings how to avoid discovery during night raids and where parents struggled with addiction and extreme poverty.

It is in neighborhoods like these where children are directed down the path toward prison instead of college, targeted unjustly by law enforcement officers and our whack criminal justice system. With a 700% rise in incarceration rates in the past 40 years, there are now 2.2 million Americans behind bars.

Starting in the 1980s, political campaigns supported reforms that would be “tough on crime” and wage a “war on drugs.” Since then, stricter law enforcement and sentencing policy changes have resulted in overcrowded prisons and increased financial burdens on states and taxpayers.

Now, there are more people serving sentences for drug-related offenses than there were prisoners for any crime in 1980. While United States citizens account for 5% of the world population, our country also houses 25% of the world’s prisoners. And, to add insult to injury, the criminal justice system in the U.S. furthers socioeconomic divides, with black men accounting for 67% of incarcerated males and Latinos being twice as likely to serve jail time as white men for the same crime.

Sentences and punishment are not tantamount to the crime. Similar infractions are not judged in the same way in every court. Prison does not reform the convicted individual. Within three years of release, two-thirds of convicted criminals will find themselves back behind bars.

Where does all of this leave us? That six-year-old whose crack-addicted mom couldn’t provide for her family has a criminal record at the age of eleven. His brother is in prison because he can’t pay the court fees after an altercation with another boy in the schoolyard. Taxpayers contribute to the $40,000 price tag to keep this man in prison for a single year.

And when he gets out? Tell me: how likely would you be to hire a criminal?

Hope for prison reform seemingly ended with the election of President Donald Trump, especially after failure to pass the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act in 2016, which would have allowed for a major overhaul on sentencing minimums and the “three strikes, you’re out” provision. The latter has resulted in “life without parole” sentences for people with three (even non-violent) drug offenses.

But the President’s adviser and son-in-law Jared Kushner is promoting programs to help prisoner re-entry into society upon release. With no funding allocation for such programs, we’re left wondering how they will be paid for, how effective they will be and when sentencing reform will come (if ever?).

We cannot continue to tear apart families, ruin lives and funnel taxpayer money into the criminal justice system. It is inherently wrong to prioritize removal from society over reform and treatment for the mentally ill and drug-addicted population that often ends up in the U.S. prison system.

Re-entry programs for returning convicts is a welcome start, but for those serving life sentences, Kushner’s attempts at reform mean nothing. For now, life goes on around incarcerated men and women while they remain stuck in a system that delivers anything but justice.