Recently, the Trump administration introduced a new regulation on immigration based on a green card or visa applicant's levels of income and education, as well as any history of receiving benefits or aid. Some used the poem, written by Emma Lazarus, on the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty to question this new rule, mainly quoting the line, "Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free."

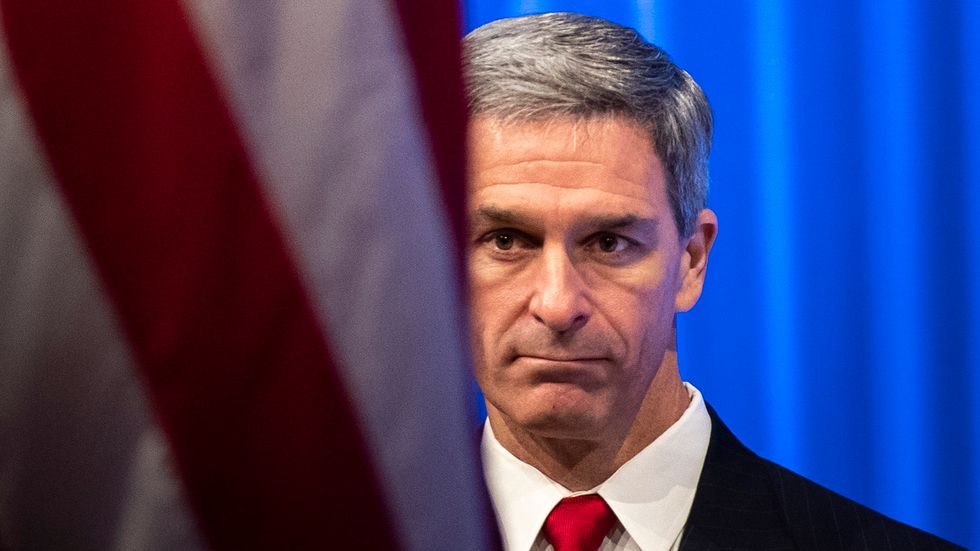

The use of this poem prompted Ken Cuccinelli, current director of US Citizenship and Immigration Service, to revise Lazarus's words in an NPR interview. Cuccinelli's take on the meaning of the line was, "Give me your tired and your poor who can stand on their own two feet and who will not become a public charge." In a later interview, he added, "Of course that poem was referring back to people coming from Europe where they had class-based societies."

Cuccinelli's take on Emma Lazarus's poem is extremely problematic. It seems that Cuccinelli would judge whether or not someone somehow 'deserves' to immigrate to the United States based on their financial standing and level of education. Deciding that someone is deserving of becoming an American citizen means also deciding that someone else is undeserving. How can anyone truly call someone undeserving of becoming a citizen, especially based on financial standing or education? There are natural-born American citizens who have not been able to meet those same standards. For people who want to argue that immigrants can pose a threat or present instances of immigrants being criminals, there are plenty of natural-born citizens who are also criminals: domestic terrorism, after all, has been a very prominent threat recently.

The issue with the implication that someone can be undeserving of US citizenship is that immigrants and even just those who apply for green cards or visas are, in a way, treated as inferior. They are not treated as equals to American citizens, especially not to natural-born citizens. Even in arguments against the discrimination of immigrants, people still feel compelled to use the deserving argument. It's always a discussion of how immigrants contribute to American society, how hard they work, or how accomplished or talented or educated they are.

What about those who aren't as accomplished, or those who aren't privileged enough to afford an education?

What about those who aren't what we perceive as "above average" or "talented," those who only wanted a fresh start or a better life?

And why do we measure an immigrant's worth as a person by these standards, by their perceived contribution to the country?

They're still people, and what they really deserve is to be treated as such.

Cuccinelli's interpretation of Lazarus's poem as specifically applying to European immigrants isn't an acceptable argument either. He can draw on the past if he likes, but the fact is that the United States has changed, and the interpretation of the poem should change with it. If Cuccinelli wants to stay in the past, then he can't cherry-pick which parts of history he wants to stand by: the poem was also placed on the Statue of Liberty while the Chinese Exclusion Act was still in effect.

Cuccinelli's insistence that the poem refers to Europeans is very telling. He seems to have a view of what American citizens should look like, one that excludes people of color. Perhaps the Trump administration really intends to limit immigrants from countries that Donald Trump previously referred to as "shithole countries."

No matter the intent of Cuccinelli's statement, it's clear that the Trump administration favors those who are privileged: namely, those who are rich and white. These are the people who are deemed deserving of citizenship.

Ken Cuccinelli's statements are upsetting and discriminatory. In the end, does anyone really have a right to decide that anyone is undeserving of citizenship based on their financial standing, education, or any other perceived measure of success? As American citizens, we need to start viewing all immigrants and those applying to immigrate as equals and, ultimately, as people.

Photo by

Photo by