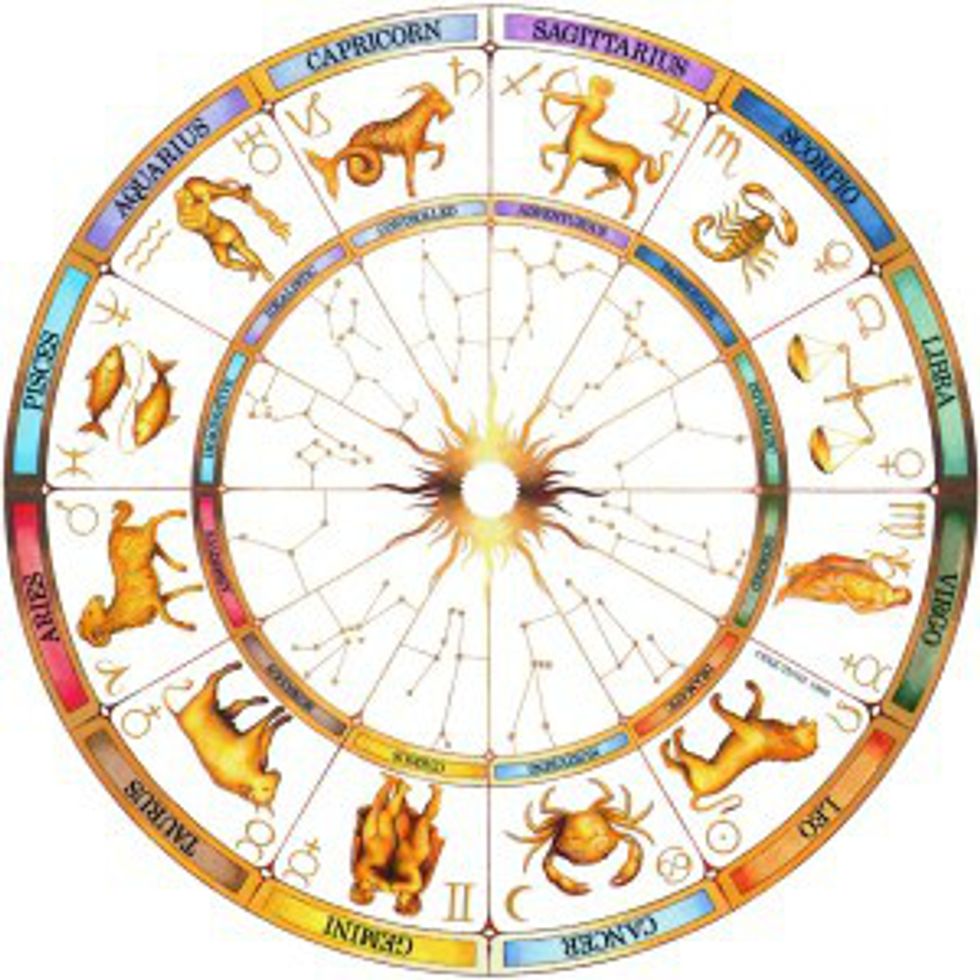

Karl Popper’s falsification criterion for determining the difference between science and pseudoscience (also called fake science) is insufficient as a solution to the demarcation problem: the problem of determining what is and isn't science, because it does not rule out pseudosciences like astrology from being considered.

One objection to this argument is that Popper’s theory actually does rule out astrology as a pseudoscience, rather than a science. Since eventually pseudosciences will have to resort to ad hoc explanations for their mistakes, whereas sciences make claims that are either falsified or at the very least falsifiable. An example of science is the theory of planetary gravitational orbits, which was subjected to testing when calculations appeared to go wrong. If this test had been falsified, then science would have had to mark potentially the entire scientific paradigm that it existed false. On the other hand, astrologers will never shift their entire paradigm. Instead, they will simply continue to explain away their inaccurate ideas until falsification becomes impossible.

This objection must be responded to by pointing out that it is not always true. Sometimes, what many would consider pseudoscience does make radical changes to its core beliefs based on falsification. A new sign was added to astrology, for example, in response to tests concerning the future and the rotation of the planet on its axis. Alternatively, at times science and the scientific community that practices, it seems unwilling to change in the face of falsification. For a long time, scientists stubbornly refused to believe that x-rays were harmful to pregnant women and their babies, because the person who made this discovery, Dr. Alice Stewart, was a woman. Eventually, her work did convince other scientists to believe rightly that x-rays could be dangerous, but this was not so much in response to the falsification of their previous theories. It was in response to other pressures, and it took years for her data to be accepted in the scientific community.

As such, it can be seen that although appearances may point to its correctness at times, Karl Popper’s falsification criterion is lacking as a solution to the demarcation problem, because it does not truly define science or pseudoscience at all times.